Scientists aren’t sure exactly how bad air pollution is in Africa but think it’s worse than we thought

Somerset West, South Africa

Somerset West, South Africa

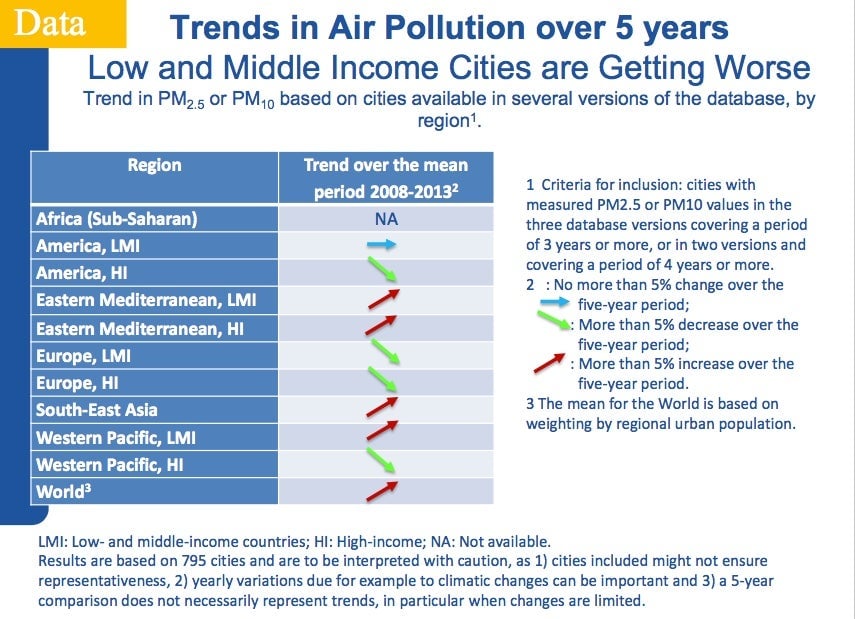

When Carlos Dora of the World Health Organization put up his slide on air pollution estimates around the world, there was a blank space where the figures on Africa should be. The “NA” he used is indicative of how little is understood of air pollution on the continent, even as it becomes one of the largest threats of a rapidly urbanizing environment.

Dora, a coordinator in the WHOs Public Health, Environment and Social Determinants of Health department, was speaking this week at a conference sponsored by the Novartis Foundation on how the continent’s rapid urbanization will affect the health of many citizens.

“It’s a very big problem in Africa,” Dora told Quartz. We have to create more of the ground level monitors but I have no doubt that just by being in African cities it’s quite clear.” The data they have gathered has been drawn from satellite images, air pollutant estimate models and existing emission inventories, said Dora.

In more industrialized countries, factories, cars and power stations are blamed for polluting the air. In Africa, the causes are subtler, hiding in plain sight. Kerosene, used in homes all over the continent to light homes and cook foods, is a deadly threat that many people simply didn’t know about (pdf), said Dora.

It is the impoverished areas on the outskirts of cities that are the worst affected, where city officials have not been able to provide services at the rate that these communities have grown. Here, where homes are built in close proximity, coal fires pose another danger, even when homes have chimneys or cook outdoors. Without proper waste removal, people often burn their garbage, emitting even more toxins into the air.

Air pollution causes over a quarter of deaths by non-communicable diseases globally, causing a host of illnesses ranging from pneumonia to dementia. While public health strategies have been introduced to raise awareness and prevent the symptoms of non-communicable diseases, air pollution remains absent from that message especially in Africa.

The annual number of deaths from outdoor or ambient air pollution rose sharply—by 36%—from 1990 to 2013 from what was a low base, according to the OECD. Indoor air pollution rose by 18% during the same period from what was already a relatively high base of 400,000 deaths in 1990.

Dirty air has led to the premature deaths of 712,000 Africans each year, more than the toll of unsafe water, malnutrition and unsafe sanitation. In September last year, researchers calculated the monetary cost of air pollution in Africa for the first time: $215 billion from outdoor pollution and $232 billion from indoor pollution (based on 2013 figures).

The solution to reducing air pollution, however, is complex, and requires everyone from urban planning, waste management to transport authorities to work together to address what is quickly becoming a health crisis. Renewable energy, said Dora, will be pivotal in reversing the damage of air pollution.

Citizens would need to create the demand for cleaner solutions to encourage corporates and governments to act, but that would require public awareness that simply isn’t there yet.