An ingenious European lawsuit could finally provide a realistic way to stop Brexit

Jolyon Maugham doesn’t mind a tough fight. He was rejected from one of his first jobs after university for being a man, instead of a woman named Joleen that the employers thought the temp agency was sending. He filed a sex discrimination case and won.

Jolyon Maugham doesn’t mind a tough fight. He was rejected from one of his first jobs after university for being a man, instead of a woman named Joleen that the employers thought the temp agency was sending. He filed a sex discrimination case and won.

And now Maugham seems to be taking on the majority of Britons who voted to leave the European Union (EU). Along with some politicians, he has filed a case that could allow the UK parliament to reverse Brexit if they so wish. He now regularly gets online hate messages from what he calls “a small group of angry and loud individuals”—but that’s not going to stop him from the pursuit.

“We live in a very, very, very uncertain world,” the 45-year-old, London-based lawyer told me. “Everyone has a stake in the answers we are seeking.”

As part of the EU, the UK currently enjoys no barriers to trading with 27 other member nations. Technically, the UK notifies the EU that it’s leaving by triggering Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which binds the members of the EU. When that happens, Article 50 says the UK gets two years to negotiate the terms of its divorce with the 27-nation bloc, currently its biggest trading partner. If during the process the UK also reaches a trade deal it likes, then Brexit would be hailed as a success.

Where things get tricky is if the UK fails to secure a satisfactory trade deal with the EU post-Brexit. According to Article 50, that means the UK just drops out of the EU with no new agreement in place. The UK prime minister Theresa May has vowed that, if that happens, the country will still leave and trade with the EU under rules set up by the World Trade Organization (WTO). As a member of the WTO, however, the EU would be able to levy stifling import and export taxes on British products, in order to make products made within its 27-nation bloc more desirable than those from the UK.

That is why Maugham thinks the UK should have a way out. The world could change a lot in two years. If the UK isn’t able to secure a good trade deal, it could be better off staying in the EU. And to do that, it should be able to revoke Article 50. The thing is, even David Davis, secretary of state for the appropriately named Department for Exiting the European Union and thus the government’s lead on Brexit, doesn’t know if that’s an option.

“We don’t intend to revoke [Article 50]. It may not be revocable. We don’t know,” Davis told a committee of lawmakers in parliament in December.

Ignorance is bliss

In other words, the UK government is about to make a monumental decision—which could jeopardize its economy and even threaten the union between Scotland, Wales, England, and Northern Ireland that make up the United Kingdom—without legal clarity on what happens next. But, Maugham says, that’s not what’s unusual here.

“The government constantly lives in a world where it doesn’t know what the law is,” he said. “What is unusual about this situation is that the government does not want to know what the law is.”

Article 50 is confusing because it was never intended to be used. “It is like having a fire extinguisher that should never have to be used. Instead, the fire happened,” Giuliano Amato, a former prime minister of Italy who helped draft the Lisbon Treaty, told the Independent. It was included to assuage nationalists that no member state of the EU was forever bound to remain part of the union.

The only legal clarity available in the text is that if the UK is unable to secure a deal in two years, it can request an extension, which must be approved unanimously by the remaining 27 members of the EU. On revocation and halting the exit process, legal commentator David Allen Green says the article text is “silent.”

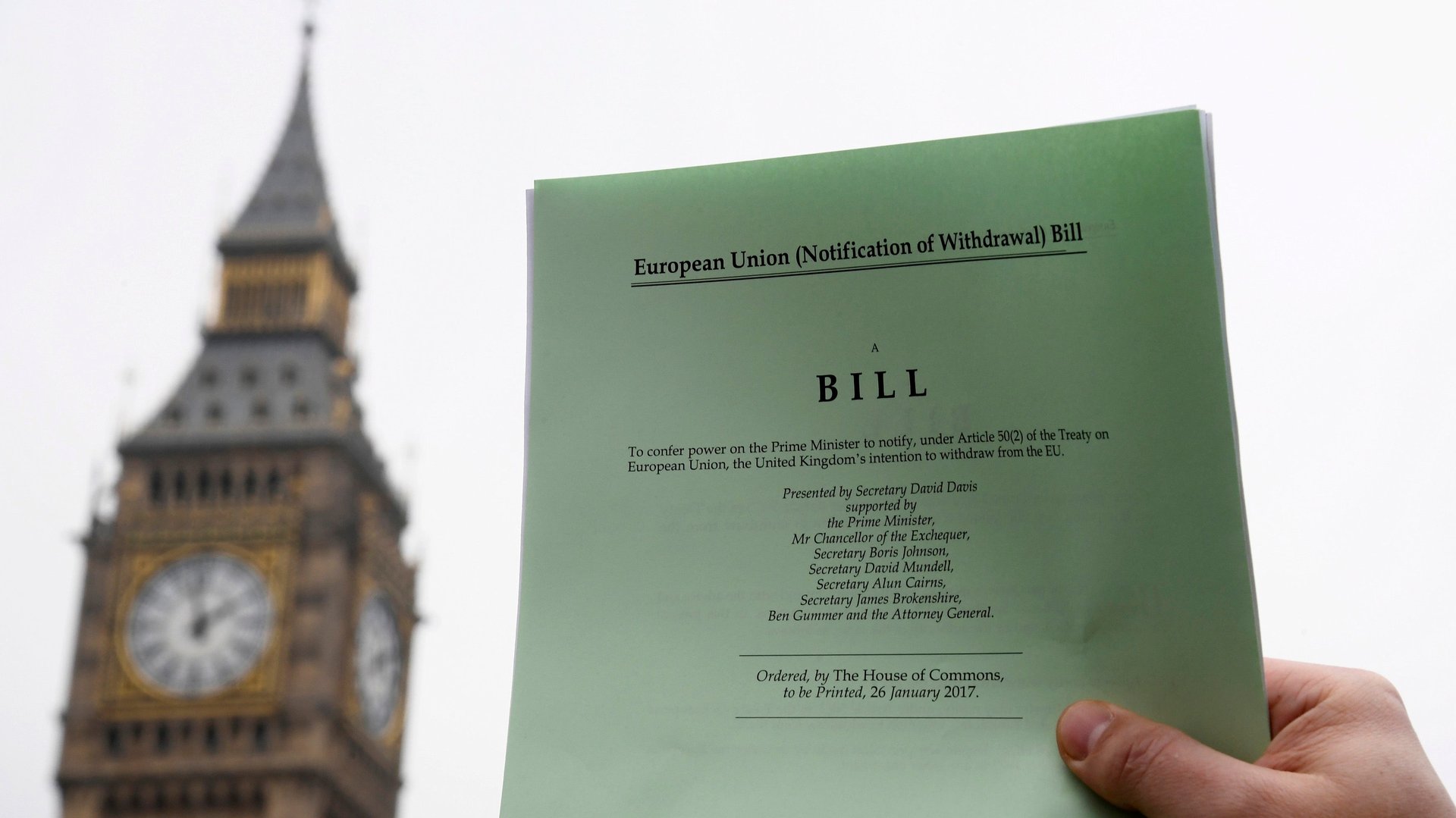

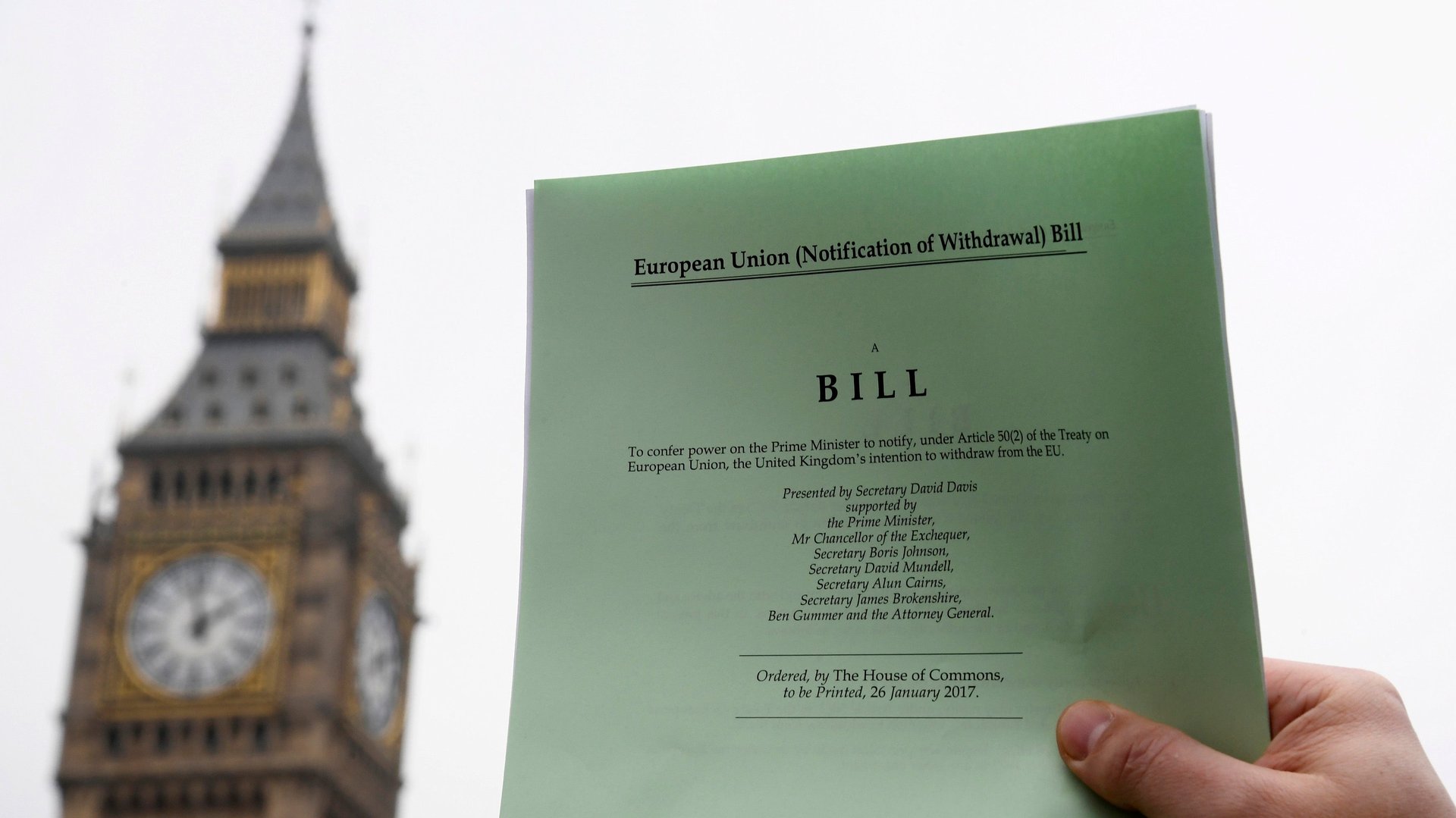

It became clear that the UK government did not want to wade into the legal details soon after May became prime minister. Her government initially assumed it had the legal right to trigger Article 50 without parliamentary approval. But then an investment banker, a Spanish hairdresser, and a British expat in France (who crowdfunded some of their legal fees) took May to court over her claim that she could trigger Article 50 on her own. She lost, first in a high court and then the supreme court, and now needs approval from both houses of the parliament to begin the Brexit process.

Even if May gets the approval she needs to trigger Article 50, the Brexit process is likely to get messier. In Maugham, the government has a skilled opponent and the parliament an accomplished ally. His case, filed in a European court, seeks crucial answers that the government doesn’t seem interested in finding out. Chief among them: once triggered, can Article 50 be revoked?

Smooth operator

I met Maugham on a chilly London morning at his office in Devereux Chambers, located not too far from the UK parliament. He’s a highly accomplished barrister; he’s been given the title of Queen’s Counsel (QC), an honor bestowed on to only 10% of British trial lawyers.

“For some,” he said, the QC rank “is a passport to much higher professional fees. But it can also be passport for you using the title to shape the society you want to see.”

The 65-page application to be considered for the QC title requires 25 references from colleagues, clients, and judges. Once the title is given, it can’t be rescinded. “So once you are a Queen’s Counsel, a layer of control over you is removed,” Maugham said. “You don’t need to go back for references, unless you want to become a judge.” That puts him on pretty solid ground to take what would otherwise be a professional risk to engage in the legal battle over Brexit.

Maugham started thinking about the case he would eventually file the day after the referendum. “I’m working on delivering the outcome that I had identified on about an hour-and-a-half of sleep on June 24,” he told me.

It took six months to figure out just how he would go about doing it. To start, he crowdfunded from more than 2,000 donors the £70,000 ($88,000) needed to pay solicitors’ fees.

Maugham is no pauper. He bought a piece of property in Sussex with a number of historic windmills on the site for £1.1 million in 2012. He’s currently restoring those windmills, a project estimated to cost £750,000 or more. But he has a good reason for asking others to pitch in. “It’s important for people to know that the case is not funded by shadowy figures or rich donors, but that it’s funded by the people,” he said. After all, 48% of Britons voted against Brexit.

Maugham is filing the case in Ireland’s high court instead of the UK’s; he thinks that will offer a quicker route to the European Court of Justice (ECJ), which supersedes UK’s supreme court in EU-related matters (at least until the UK exits the union). Even before Brexit, courts in the UK were hesitant to refer cases to the ECJ. Since the June 2016 referendum, their reluctance has increased.

“The courts feel imperiled by the political and media context,” Maugham said. “When the Daily Mail and the Telegraph attack judges as ‘enemies of people’ or ‘haters of democracy,’ that creates a climate that will affect how judges appreciate their role.”

“Judges are human beings. They read the papers,” Maugham said. “They will be afraid of further attacks on their legitimacy. They will strive to avoid giving ammunition to those who are likely to attack.”

Playing with fire

Maugham has a personal stake, too. He voted “remain” in the Brexit referendum, and is certain that leaving the EU will rob his three daughters of many opportunities. But what ultimately fueled his decision to file the case was the injustice he has seen in his practice of many years fighting tax-avoidance cases, trying to recover money that corporations owed to the government.

“Our systems and institutions don’t protect the weak and the poor,” he said. “For many years, I’ve been working on ensuring that our legal system works for those who do not have much. This Brexit case is a natural, logical extension of that work.”

Maugham has long had a bit of a public face: he’s been blogging about his tax cases for some time now, and he’s gained a sizable readership. But the project also brought the scorn of his colleagues, who thought time blogging meant time not billing clients. “My colleagues said the blog was ‘the longest suicide note in history of a successful professional practice,'” Maugham said. “I don’t mind because I’m just not that much motivated by money.”

To work on the Brexit case, Maugham has all but given up work. On top of that he has to deal with online hate and trolls. His way of dealing with the abuse has been to stay silent, as best he can. “I’ve mastered the art of Twitter,” he said.

It also helps that he has a strong case. Maugham and his co-plaintiffs only filed it after consulting with leading legal academics across Europe. Even the author of Article 50, John Kerr (who, ironically, is a Scottish member of the House Lords) believes it’s revocable. “During [the negotiation] period, if a country were to decide actually we don’t want to leave after all, everybody would be very cross about it being a waste of time,” he told the BBC. “They might try to extract a political price, but legally they couldn’t insist that you leave.”

Maugham has petitioned the Irish high court to hear the case on an urgent basis, but there’s no telling how long it’ll take. In the meantime, Maugham will keep busy. He’s launching the Good Law Project later this month, an organization he says will file strategic legal cases, like his Brexit case, to drive a progressive agenda. The focus is on holding the UK government accountable on tax avoidance, greater social mobility—and delivering Brexit in accordance with the law.