Sorry America, history proves Donald Trump is not the first US president with totalitarian impulses

Which dictator is most like Trump? Commenters have been conflicted. The Pope obliquely suggested that Trump’s rise paralleled Hitler’s. The Washington Post wondered whether Trump was more like corrupt oligarch Berlusconi or the dictator Mussolini. Slate suggested Trump’s lies were similar to Stalin‘s. The exact dictator may change, but the general comparison remains the same—in his disdain for the truth, his attacks on free speech, his conspiracy theories, and his attacks on minorities, Trump is un-American.

Which dictator is most like Trump? Commenters have been conflicted. The Pope obliquely suggested that Trump’s rise paralleled Hitler’s. The Washington Post wondered whether Trump was more like corrupt oligarch Berlusconi or the dictator Mussolini. Slate suggested Trump’s lies were similar to Stalin‘s. The exact dictator may change, but the general comparison remains the same—in his disdain for the truth, his attacks on free speech, his conspiracy theories, and his attacks on minorities, Trump is un-American.

But the uncomfortable truth is that America is no stranger to authoritarian rule. The United States has a long tradition of democracy and freedom, but it has an equally long tradition of totalitarian restrictions on speech and repressive political violence.

To start, many presidents before Trump have restricted press freedoms. John Adams, like Trump, was a vain and touchy man, who deeply resented criticism in the press. In 1798, taking advantage of tensions with France, Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts, criminalizing criticism of the president, Congress, or the US government. Newspaper editor John Daly Burk and Republican representative Matthew Lyon of Vermont, among others, were arrested for criticizing the president and his policies.

Adams’ Sedition Acts are often dismissed as an early aberration—a dalliance with totalitarianism that was eventually abandoned. Yet US press restrictions have been revived throughout our history, especially in wartime. Notoriously, the Sedition Act of 1918 made opposition to US participation in World War I illegal.

While Trump threatened to prosecute Hillary Clinton once he gained power, president Woodrow Wilson’s administration actually did prosecute socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs. Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison for delivering an anti-war speech, which the government said violated the 1917 Espionage Act. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction and Debs remained incarcerated until 1921, when his sentence was commuted by Wilson’s successor, Warren G. Harding.

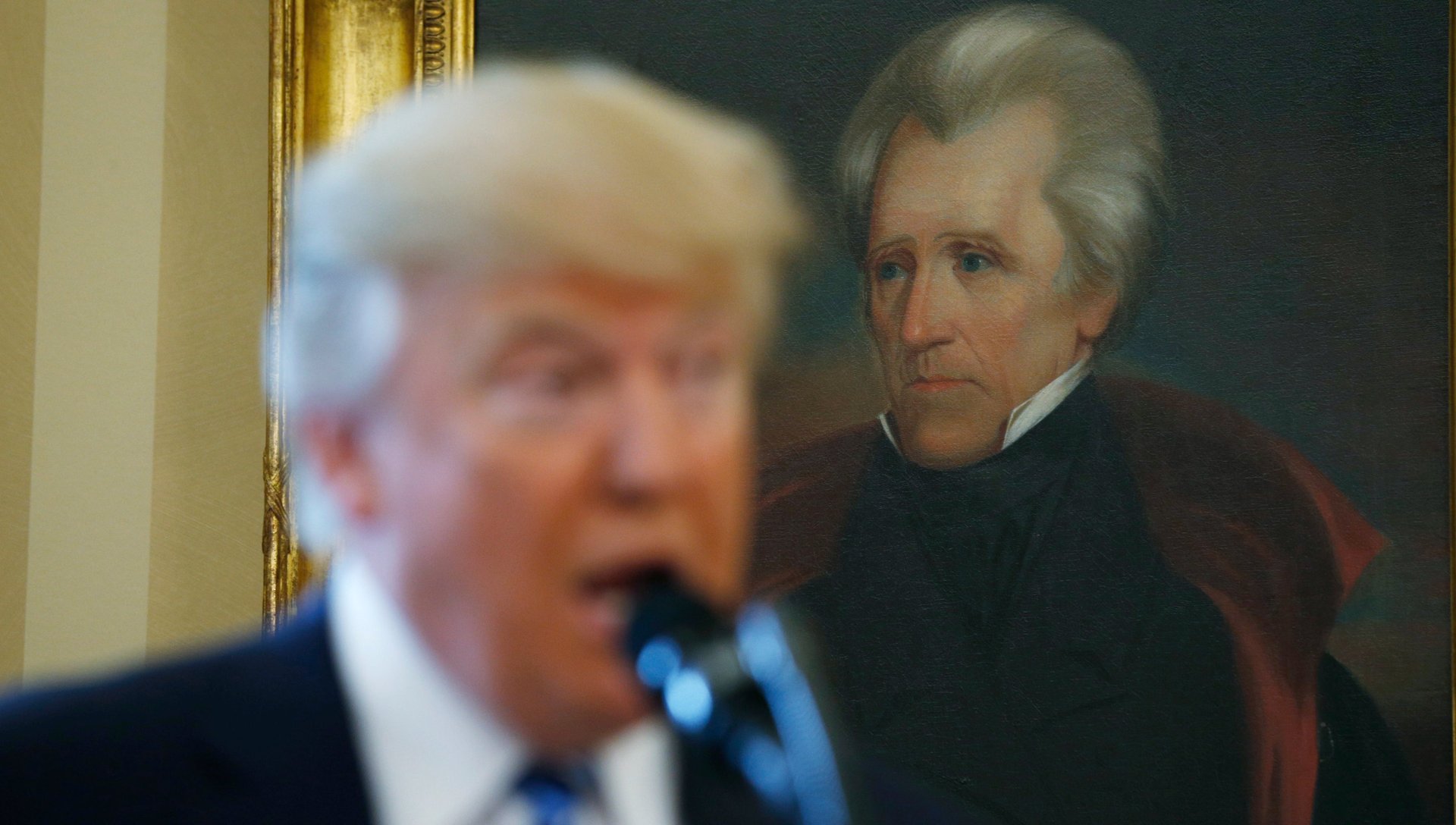

America’s worst totalitarian moments, however, go far beyond instances of presidents using state power to persecute political opponents. Andrew Jackson’s sweeping Native American removal policies would today be considered akin to ethnic cleansing; his administration orchestrated the killing of thousands of American Indians as well as the the theft of land and property of people who had no recourse to the law—a nakedly racist, authoritarian power grab,

In addition, for close to the first 100 years of its history, the US maintained a massive gulag in the American South. In 1860, before the Civil War, almost 4 million people, or 13% of the population, were considered slaves. Black people in the South were, of course, not allowed to criticize the government; in many Southern states, teaching an enslaved person to read or write was a crime in itself. Such restrictions were de facto renewed in the Jim Crow era in the 20th century; Richard Wright’s Black Boy vividly describes his furtive efforts to obtain library books in the South in the 1920s. For much of its history, America, for many of its citizens, was essentially an authoritarian regime—a place of paranoid surveillance and petty restrictions, in which protest, or even a wolf-whistle, could be punished with violence and death.

Nor is this racist, totalitarian past over and done with. The US still maintains the largest prison population in the world. Mass incarceration—which systematically targets, prosecutes, and disproportionately imprisons millions of black and brown men, among other Americans—is understood by many to be the modern continuation of Jim Crow. Citizen protests are still met, at times, with a militarized response. State violence against dissenters is not a foreign concept.

There are strategic reasons, perhaps, to emphasize Trump’s un-Americanness. Freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and liberty in general are cherished US values in theory, even if they aren’t always honored in fact. Comparing Trump to Mussolini, for example, is a forceful way to emphasize his betrayal of Constitutional ideals. Trump’s brazen lies and his open contempt for freedom of speech contrast with American traditions—it’s worth underlining that.

But Trump’s totalitarian impulses also mirror shameful events in American history. And his particular brand of authoritarianism will likely build on precedents set by Americans like John Adams, Woodrow Wilson, Andrew Jackson, and Jefferson Davis.

American authoritarianism has most often, and most virulently, intertwined with American racism. Trump may well work to clamp down on the press freedom in various ways, but some of his most sweeping promises—a Muslim registry, mass deportations, a crackdown on protests against police violence—target marginalized groups. Anti-authoritarianism in the United States—before, during, and after Trump’s reign—is inseparable from citizens’ demand for universal civil rights.

Remembering America’s authoritarian past is a reminder that authoritarianism is not unique to Trump. Slaveholders in the South, Jackson Democrats, Federalists under Adams, pro-war partisans under Wilson—there are always going to be some Americans who see in repression an opportunity for power and profit. But there have also always been those who resisted. Trump may be indirectly following in the footsteps of past executives, but so too are his opponents. Resistance to totalitarianism—from the abolitionists to anti-war socialists to Black Lives Matter and #NoDAPL—is a strong American tradition as well.