The art of conversation, explained by the only artist to get eight US presidents to sit still

Anyone seeking to meet the great artist Everett Raymond Kinstler should be prepared to talk. The art of the conversation is as much a part of his toolkit as his well-worn paints and brushes. An hour into my interview with the 90-year old painter, I realized he had been asking all the questions. When I tried to get one in, he smiled and said, “I’m showing you how I paint.”

Anyone seeking to meet the great artist Everett Raymond Kinstler should be prepared to talk. The art of the conversation is as much a part of his toolkit as his well-worn paints and brushes. An hour into my interview with the 90-year old painter, I realized he had been asking all the questions. When I tried to get one in, he smiled and said, “I’m showing you how I paint.”

Often compared to John Singer Sargent, Kinstler is perhaps America’s most important portrait painter working today. From John Wayne, Dr. Seuss, Katherine Hepburn, and Salvador Dali, Kinstler has immortalized scholars, socialites, movie stars, politicians and eight US presidents, including Donald Trump. (He’s still hopeful that Barack Obama will call on him one day.) Many of his paintings hang at the mythic The Players social club in New York, and no less than 100 of his paintings and drawings are preserved in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

The art of the interview

Interviewing his subjects allows Kinstler to glean an “angle,” much like a writer would do, he says. He often avidly researches his subjects, sometimes even interviewing their peers to develop a unique point of view to summarize their character.

Kinstler puts subjects at ease by regaling them with fantastic anecdotes and trivia about his dalliances with the rich and famous. Having worked in Hollywood, Washington, DC and New York for so long, he’s bound to know any famous personality you mention, instantly sparking a connection.

But he also always sounds genuinely curious about his subjects (and interviewers). He’s careful to direct his full attention to his interlocutor, with a concentration that is refreshing—even startling—in a time of mobile phone multitasking. A typical meeting with Kinstler warmly begins with a request, “Tell me about yourself.”

Two-time sitter Tom Wolfe attests to Kinstler’s gift for gab. “Ray is a joy to listen to from the beginning…His idea is to release your personality and get things going on a social level,” says the Bonfire of the Vanities author.

Those tactics to charm sitters into stillness for hours on end don’t work on everyone: In 2006, he met his conversational match in Donald Trump, then a New York real estate personality. Years later, when probed by Daily Beast about the experience of painting Trump Kinstler matter-of-factly likened him to ”a roulette wheel,” admitting: “He jumped from subject to subject so quickly that it was impossible to get a conversation going with him.”

But Kinstler, who divides his time between his airy Gramercy Park studio and his home in Easton, Connecticut, didn’t become a painter of presidents through indiscretion. When probed if Trump, now the US president, ever displayed his signature locker-room language during their sitting, Kinstler replied, “Yes he has. But you’re not going to hear it.”

Communicating politics through an image

Kinsler’s mentor was James Montgomery Flagg, creator of the iconic Uncle Sam “I Want You” poster, and he is keenly aware of the power of an image. He fusses over the subtlest of signs: The symbolism conveyed by the sitter’s outfit, the painting’s setting, the size of the canvas, the placement of the finished painting in a building and even the politics of the commissioning institution.

“The worse thing you can say about my work is ‘I love it, it looks just like a photograph,” says Kinstler. ”If that’s the case, what do you need me for?” A portrait should capture much more than the subject’s mere likeness, he explains.

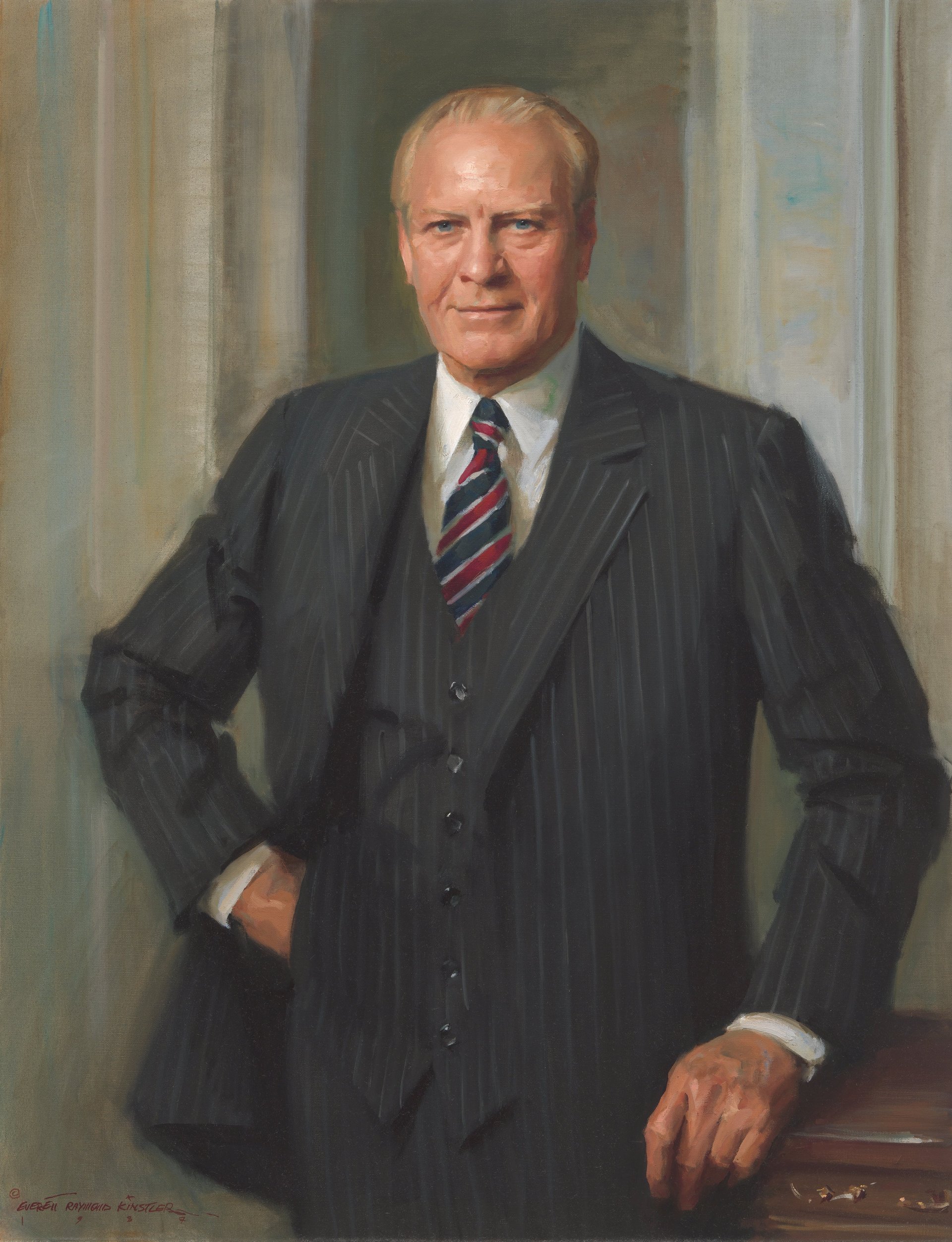

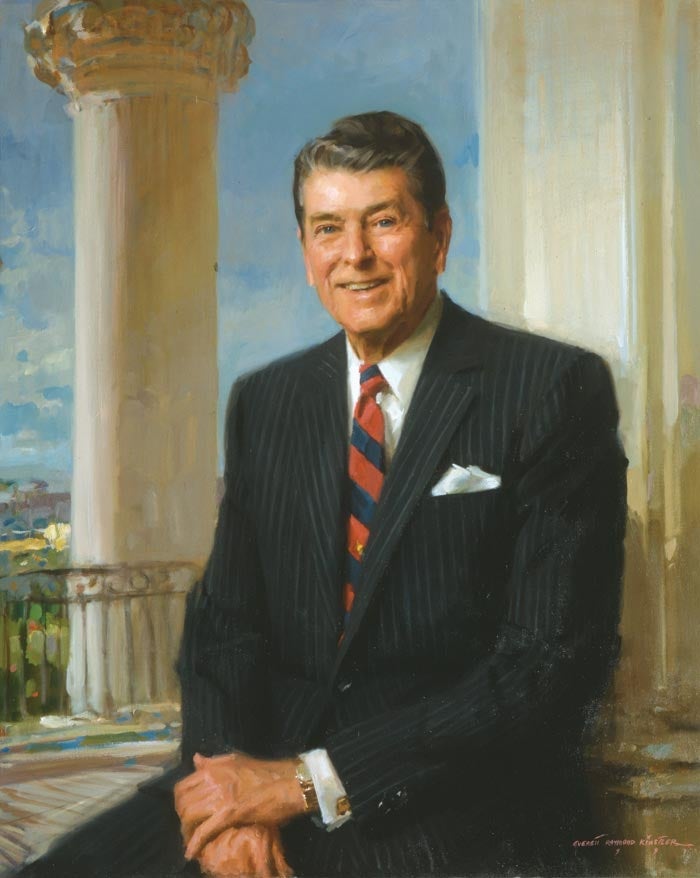

A former comic book artist drawing for pulp magazines like Doc Savage and The Shadow, Kinstler got his start as a portraitist when he was asked to paint the US ambassador to France. This led to another high profile assignment, with the portrait of Forrest Mars Jr, heir to the Mars candy fortune. A succession of referrals followed. Over the years, Kinstler built his professional reputation on his ability to create ”objective” portraits that never fail to please his sitters. His portraits of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan have both been designated “official portraits” by the White House.

Except for Hellen Keller, who was painted posthumously, Kinstler insists that every subject allocate time for a proper sitting. Nicole Parent Haughey, Harvard Club’s first female president, recalls that that she sat for Kinstler about six to 10 times. She and Kinstler debated about creating the right image, trying out chairs, locations and outfits, with Kinstler rejecting a navy blue ball gown she originally proposed.

Thinking about the portrait’s message, Kinstler suggested breaking with tradition, and painting her in a smart, off-white suit to highlight her historic appointment in the traditionally male-dominated club. Haughey loves the result. “My husband will always say when he stands in front of my portrait, ‘he got you so well.”

For Reagan’s 1991 White House portrait, Kinstler also broke with tradition and painted him on the White House balcony. Reagan loved this idea, telling Kinstler he would often retreat to the second-floor vista to gaze out towards the scene of the “accident,” referring to the Washington Hilton Hotel where John Hinkley Jr. shot him in the chest in 1981.

For Gerald Ford’s 1977 portrait, former White House curator Clement Conger attempted to “art direct” Kinstler asking him to erase the “fish hook” wrinkle in the president’s brow. But because Kinstler brought up that first lady Betty Ford loved this trace of the worry that her husband felt for the country, the fish hook stayed.

Chronicler, not critic

Since Gilbert Stuart’s stately oil painting of George Washington in 1796, presidential portraiture has been part of the transition of power in the US. An outgoing president consults with historians to craft his image, while the incoming president traditionally chooses a portrait of a predecessor to decorate his office. The complete collection is preserved in the White House and the Smithsonian National Portrait gallery.

Of the seven presidents he painted in office, Kinstler says he’s worked to produce portraits worthy of the country’s highest office, even if he disagreed with his sitter’s politics. (Not all portraitists do—fellow presidential painter Nelson Shanks secretly inserted a shadow of Monica Lewinsky in Bill Clinton’s official portrait because he believed that Clinton sullied the executive office with his indiscretions.)

“I have my favorites, but how much of that has shown up in the painting? I would suggest to you, none,” says Kinstler, who confesses that he enjoyed meeting Ford the most, and Nixon the least.

“I think to paint a president of the United States, regardless of party is a great honor,” he says. “You’re not painting Nixon or Ford, you’re painting a history of the country.”