Is your Valentine still a Valentine if a robot wrote it?

If you receive a Valentine tomorrow, you’ll probably recognize the handwriting—that of your spouse, significant other, friend, or perhaps hookup buddy (hey, a girl can dream). But what if your card is not written by your beau—or even your florist? Is it still a Valentine if a robot put pen to paper? Bond—a startup that lets you send fountain pen handwritten letters from your smartphone—says yes.

If you receive a Valentine tomorrow, you’ll probably recognize the handwriting—that of your spouse, significant other, friend, or perhaps hookup buddy (hey, a girl can dream). But what if your card is not written by your beau—or even your florist? Is it still a Valentine if a robot put pen to paper? Bond—a startup that lets you send fountain pen handwritten letters from your smartphone—says yes.

“Our goal is to make it easy to send beautiful personalized things to people you care about,” says Sonny Caberwall, founder and CEO of Bond. “We think of Bond as the opposite of Snapchat,” he says; if there’s a time and place for your message to disappear, says Caberwal, “there’s a time and place for your message to last forever.” High-profile investors agree—Bond is backed by Goldman Sachs’ Gary Cohn, Trump’s top economic advisor, the rapper Nasir Jones (Nas), and Bre Pettis, former CEO and co-founder of MakerBot.

The startup was acquired by Newell Brands in April 2016 for an undisclosed amount. Bond sends millions of notes per year, and this year sent over 20,000 on Valentine themed stationary, says Caberwal.

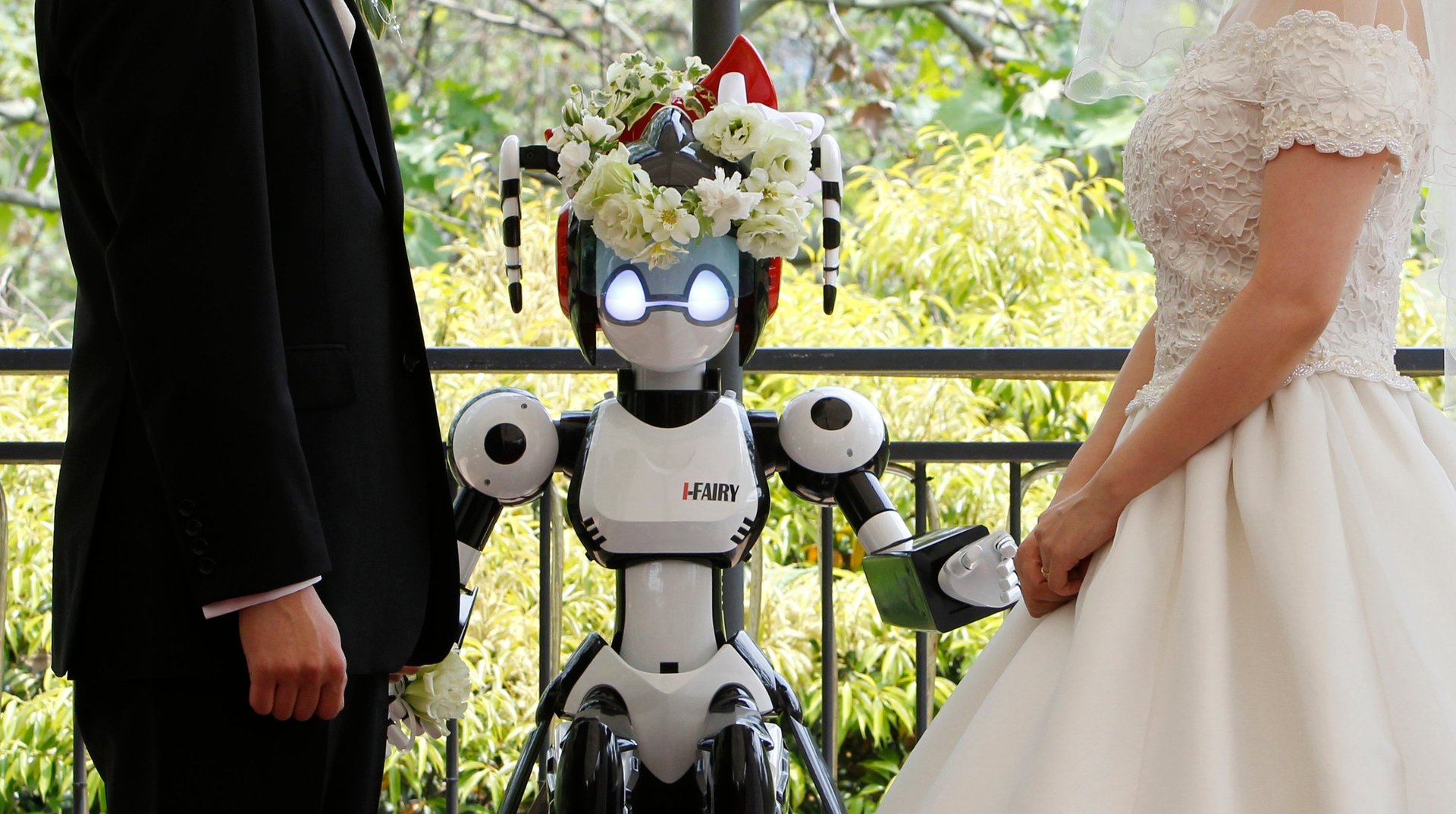

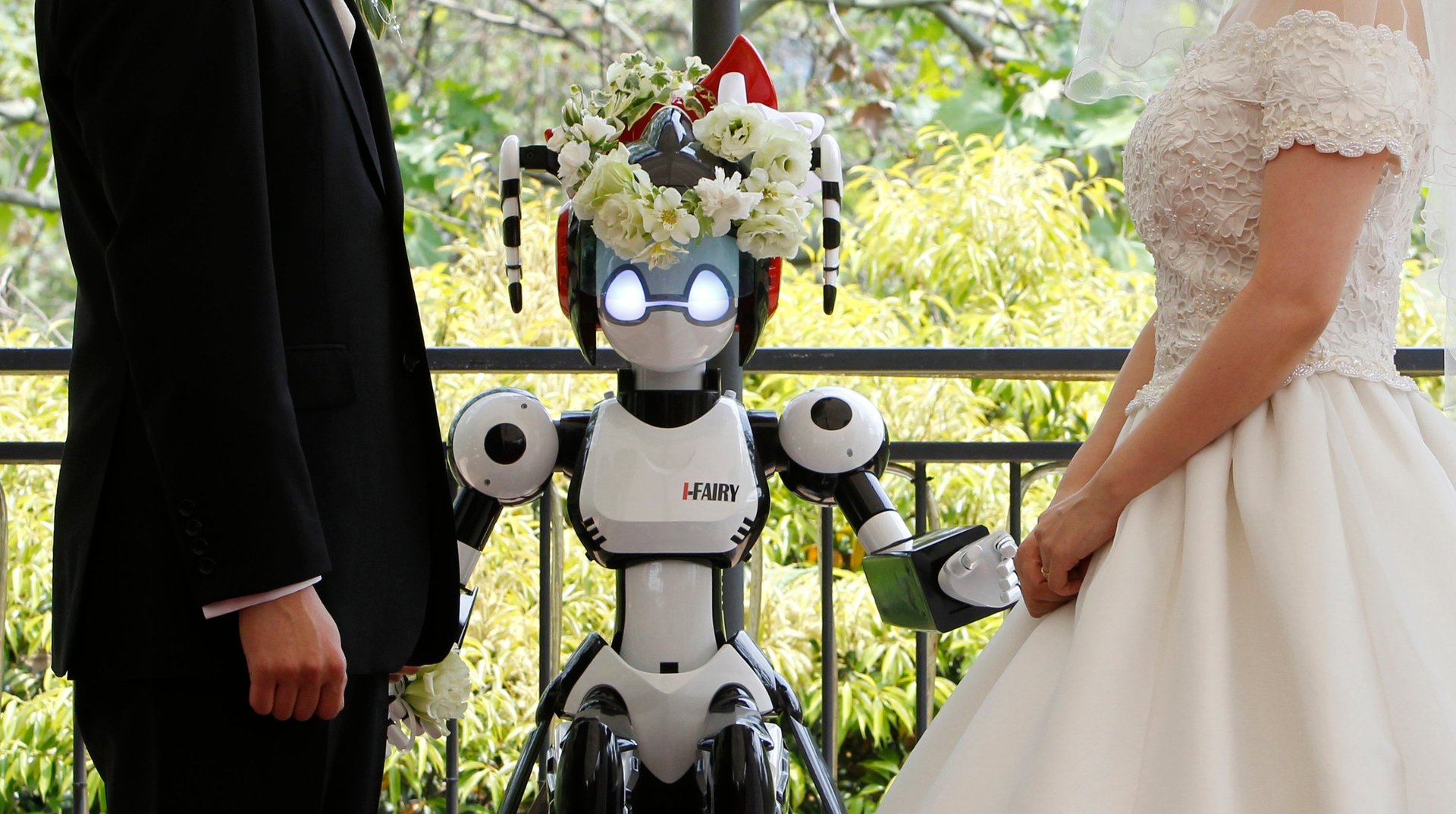

To send a Bond letter, users type their note online, provide the delivery address, and press send. Bond takes it from there—their robot, which holds a pen like you do, writes your note in programmed human handwriting on customizable stationery. Bond covers the stamp, wax seal, and delivery, all for five dollars or less.

Bond’s calligrapher designs scripts for users to chose from, from cursive to all caps. The bot mimics nuances of human handwriting—no letter is repeated exactly the same way, and spacing between letters and words varies. More, users can send Bond samples of their own handwriting, which the bots can learn to write in. The difference between a user’s real handwritten note and a Bond bot-written note can be indistinguishable.

If you’re time-deprived and efficiency-obsessed, Bond probably seems brilliant. Their product hits the sweet spot between tech and tradition, letting users streamline relationship maintenance without feeling heartless. From phony stuffed bears to flower arrangements delivered a day late, the idiom “it’s the thought that counts” rings true at Valentine’s Day. Same goes for bot-written V-day cards, right?

“The value of a message is not just words, but the time, effort, and energy behind them,” technology ethicist David Ryan Polgar explains. Polgar questions whether Bond—and companies that similarly automate intimacy—are thinking holistically about why we have Valentine’s Day cards, or other human interactions. “It’s not just for the words or the message,” says Polgar, “It’s for the fact that someone’s actually connecting to you at a base, human level.” Putting a bot between you and your intended may well blur that bond.

Amidst ubiquitous social networks, sustaining personal relationships is increasingly difficult, says Polgar. Each of us has the cognitive capacity for a maximum of approximately 150 relationships in our social network, with just five in our closest support group—though social media pushes us to think we should at least care about many more. To cope, we use shortcuts to project and automate intimacy, such as congratulatory LinkedIn messages or Facebook birthday posts. Intimate as they seem, Bond cards (especially on Valentine’s day) can be seen as shortcuts, too.

Sending a Bond note saves time you’d spend going to the store, picking out a card, writing a note by hand, finding a stamp, and delivering it to the mailbox on time. An archaic system indeed.

Yet this process has an ethical hitch: The other party doesn’t immediately know a bot’s behind the card; and they’d probably discount or think less of it if they did. If a friend receives a “handwritten,” beautifully customized Valentine—which truly took you one minute and few quick clicks to send—they will be (successfully) touched. Most likely, they’ll then spend considerably more time thinking about you, how you’re doing, and sending you a thank you note, than you invested in them.

Thus, as Polgar explains, the success of Bond’s cards “is based on a certain level of manipulation.” The same thing occurs when I mindlessly click LinkedIn’s prompt to “Congratulate Jen on her one-year work anniversary,” then Jen spends three minutes scanning my LinkedIn profile to see what I’m up to.

“While we’re busy humanizing our technology, we also want to ensure that we are not becoming botified as humans,” says Polgar, “In an effort to scale intimacy and increase efficiency, we need to be mindful of not diluting our humanity.”

Of course, Bond isn’t the first company to automate intimacy, nor will it be the last.

Take, for example, the your favorite newsletter (Perhaps, cough, the Quartz Daily Brief?). This newsletter probably calls you by your first name, tells you to have a nice day, or says that it has curated stories just for you. Your favorite publication, sorry to say, doesn’t actually care how your day goes as an individual goes. But the phrases editors use, on some level, help create a connection between a reader and a brand. Bond is simply altering that formula, becoming the brand in the middle of a personal connection between two actual people.

Whether you enjoy or cringe at a bot-written Bond card (on Valentine’s Day, your birthday, or next Hanukkah) depends on the importance you place behind the effort behind demonstrations of human emotion. Did it matter to housewives in the 1960s that their husbands’ secretaries were the ones placing the orders for their flowers? And anyway, were it not for Hallmark and its constituents preying on human emotion, Valentine’s Day might still be just another historically pagan celebration co-opted by medieval pope to in the name of a martyred Roman priest.

This ethical debate goes beyond the Valentine you may or may not receive. Automated intimacy is expanding, and sure to affect you, and your relationships going forward. If human connection is rooted in reciprocity and time investment, train your eye for metaphoric crown-imprinted wax seals, and ask yourself whether they matter. And next time you’re tempted to “hack” intimacy, remember that manipulation, too, is in the eye of the beholder.