After being James, Peter, and William, I decided to stick with my Chinese name

During the recent Lunar New Year, Columbia University students with non-Western names found their name plates ripped off from dormitory doors at several residential halls. The vandalism, which especially targeted East Asian names, stressed out students already alarmed over “the growing climate of xenophobia,” wrote a school official in an email to Asian student groups.

During the recent Lunar New Year, Columbia University students with non-Western names found their name plates ripped off from dormitory doors at several residential halls. The vandalism, which especially targeted East Asian names, stressed out students already alarmed over “the growing climate of xenophobia,” wrote a school official in an email to Asian student groups.

Some students responded by posting a video on Facebook explaining the meaning of their Chinese first names.

As the students explain, their parents ascribe a lot of meaning to their given names. One of them, Juzhi, says his name means “to turn into a better person.” Xinran (欣然) explains her name means “joy and happiness.” While such sentiments are captured in the strokes of Chinese characters, they’re lost in Western languages.

This reminds me of a constant debate: Should Chinese people adopt English first names when interacting with Westerners?

The benefits of doing so are obvious. Going by a conventional English name—but not weird names like “Candy,” “Promise” or “Devil“—makes everyone’s life easier. But my experiences studying and working in English-speaking multicultural environments in the past few years have made me realize that sticking to your Chinese name is better if you want foreigners to know who you are—and if you want to feel good about yourself.

Name games

I was William, then Peter, then James, and then William again—until I decided to just go by Ping, the last character of my given name, when I left for Hong Kong to study for a master’s two years ago.

Like many Chinese millennials, the Western names I used in my adolescent years in Shanghai were chosen by my teachers, and used mostly in English classes. My kindergarten teacher named me after Prince William because I was one of the cutest boys in class (at least according to my mother’s account, which I’ve been unable to verify). In primary school, my English teacher designated me Peter—a boring name used in many English textbooks in China, along with Linda—without asking for my opinion.

Finally, in high school, I got the chance to choose my English name on my own. Unfortunately I was caught off guard when a teacher began to ask for and record everyone’s choices.

“Huang Zheping, what about you?” It was my turn. I hesitated for a few seconds and said something I regretted immediately.

“Frodo,” I said, as I was reading The Lord of Rings books at the time. I heard snickers in the classroom.

The nice young lady seemed not to be a Tolkien fan—she said Frodo sounded French and asked for an alternative.

My mind went blank. I began to think about the names of my favorite NBA players. Kobe? That’s even worse than Frodo. LeBron? James? Fine. Let me try James.

I had to stick with James for a little over two years. Though I didn’t have many encounters with foreigners during that period, I still recall an exchange student from Edinburgh, named Fiona, looking unconvinced when I introduced myself as “James Huang.” Perhaps my introduction didn’t sound confident. If so, no wonder: I didn’t feel like a James.

In college I switched back to William. That was my first English name, after all. I introduced myself as William—more proudly this time—to foreign students and tutors. I registered several social media accounts using the name. I even carved “William” onto my iPod shuffle.

During this time I felt two identities emerge. I was Ping in my daily social circle. But I was some other guy named William to my few foreign friends and to any strangers I met who didn’t speak Chinese. Those who knew me as Ping would never know me as William—and vice versa. That was when I started to doubt the need for an English name in the first place.

Just call me Ping

I dropped the name William after I moved to Hong Kong. That was in part to avoid confusion in my master’s program. A classmate from Beijing used the name, and so did a Chinese-American internship coordinator. Since then I’ve introduced myself as Ping—short for Zheping—to both Chinese and Westerners.

According to Chinese culture, only my close friends should call me Ping. But allowing foreigners to call me that too has had its benefits. Because I was one of the few Chinese students using a Chinese first name in my master’s class, I was easily remembered by my dozens of foreign classmates. My identity was unique, and consistent across social circles. That saved me from being confused in conversations like, “Which Angie are you talking about, the Canadian one or the Chinese?” or “Oh, you mean Zhang Jian, right? I didn’t know he’s called Tommy.”

I still appreciate it, of course, when Western friends make a sincere effort—despite the clumsy pronunciation—to call me Zheping, after realizing that’s the complete version of my first name.

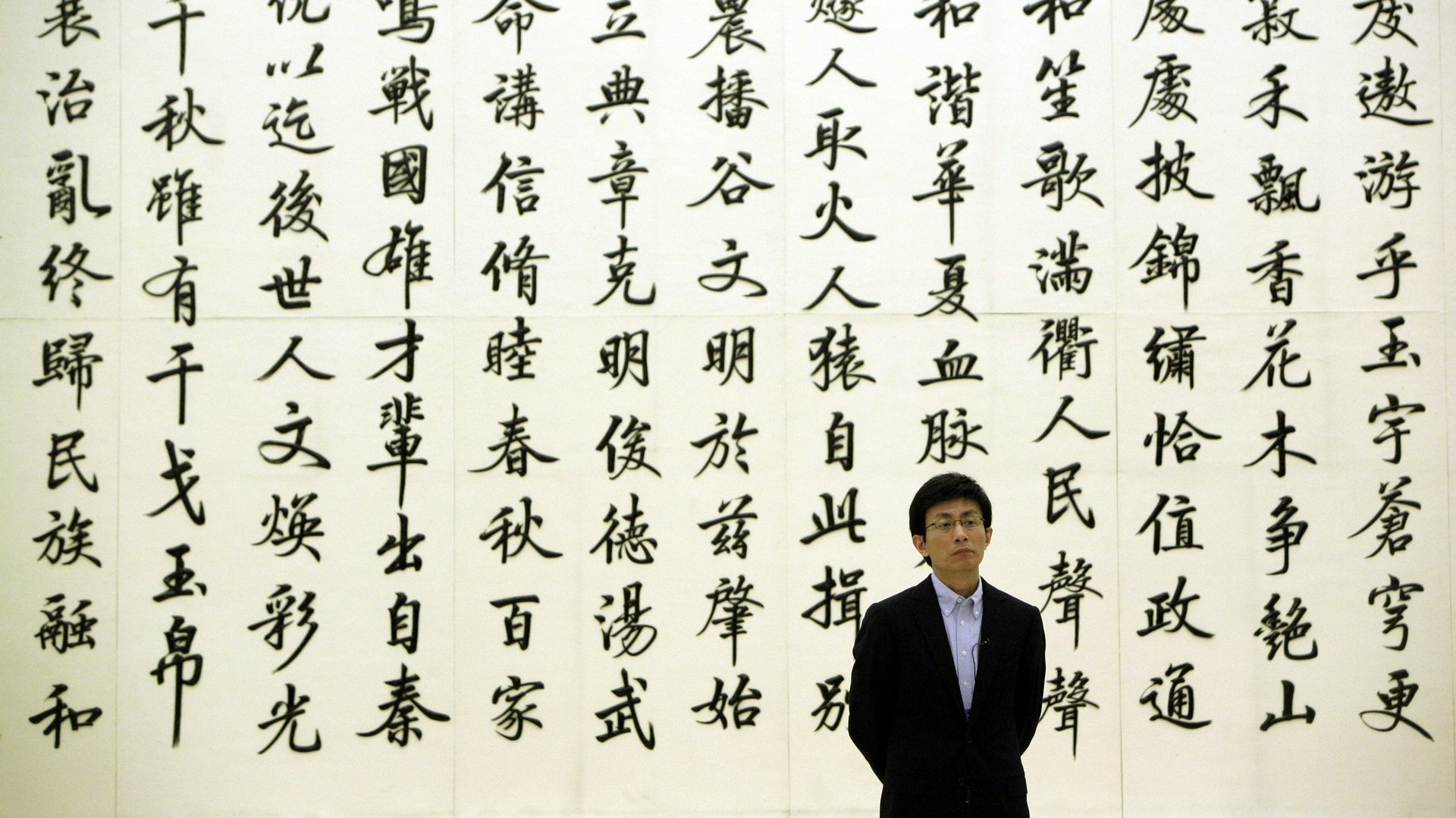

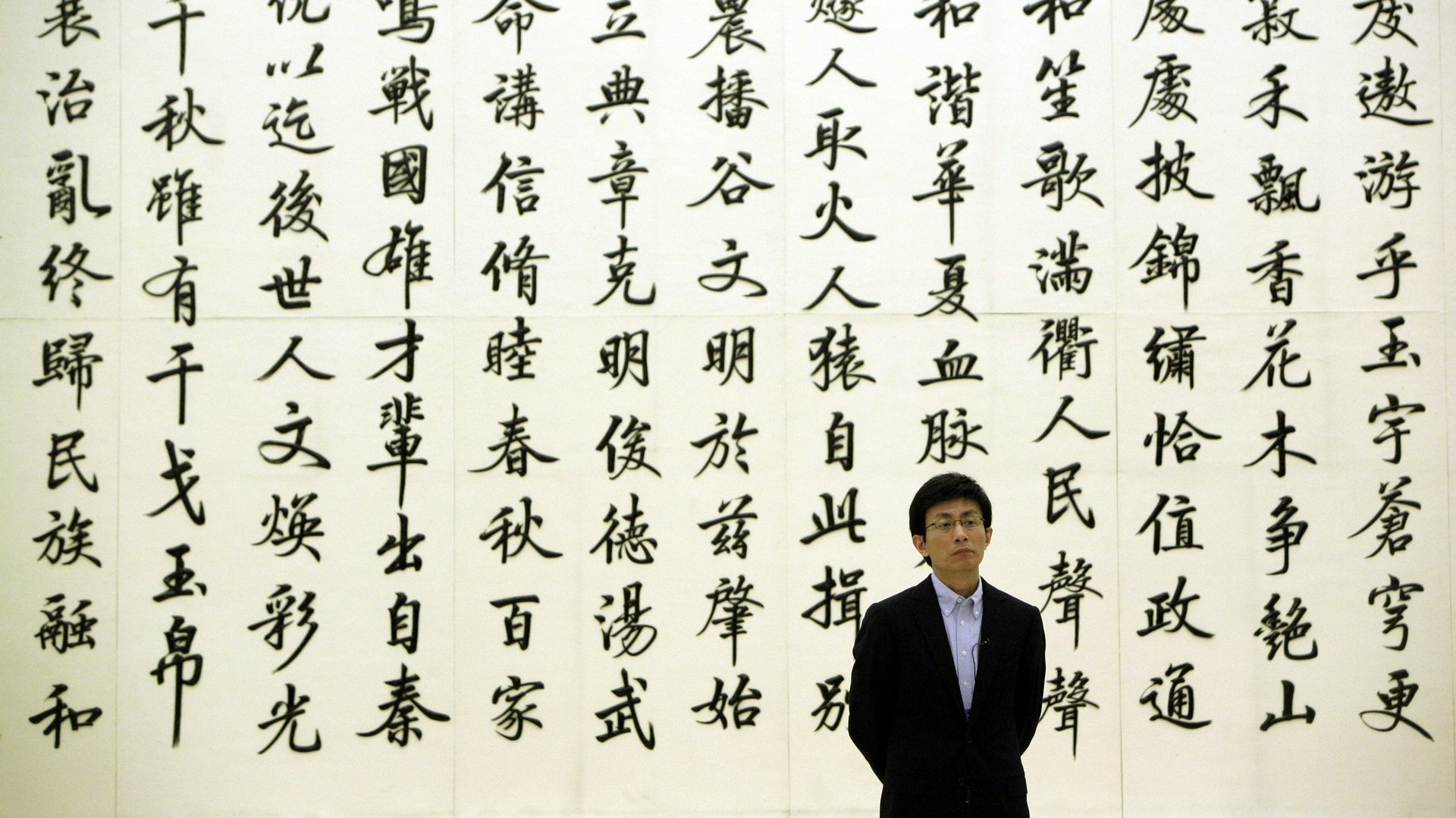

Even better is when they express curiosity about the meaning of the name, and how to write it in Chinese characters. Then I’m happy to write down 喆平. I tell them 喆 symbolically represents “double auspicious” while 平 means “safe and sound.” The name carries my parents’ simple wish for me to live a life free from accidents or suffering. The usual reply is, “Whoa, that’s a great name.”

My name—like the names ripped down from the dorm doors at Columbia University— is a reflection of the different naming cultures found in China and English-speaking countries. For many Westerners that difference is a source of fascination. If you’re Chinese and interacting with foreigners, skipping over the meaning of your given name is a shame: You miss the chance to not only add some charm to an introduction, but also share an important part of Chinese culture.

When I chose my byline name for Quartz, I went with Zheping Huang. This is the only name that I feel I belong to. I would regret it not coming along with my pieces.

My colleague Siyi Chen thinks along the same lines. In her school days in China she tried everything from Lucy to Susan to Claire. Living in the US, she’s settled with Siyi. An American toddler once called her “See”—drawing some laughter—but she enjoys the uniqueness brought by her Chinese first name, and the ensuing recognition that she is a Chinese citizen, not an “ABC” (American-born Chinese).

Of course, I’ve met many Chinese people with English names that suit them well. My friend Yilei has used the similar sounding “Elaine” since she was a teenager. Some Chinese names are too confusing in English, among them He Shiting (何诗婷), a common name for girls. And in any case, whether to have an English name is a personal choice.

But my point is, if अनिका is just Anika, and かいと just Kaito, why can’t 小明 just be Xiaoming?