Silicon Valley’s gender gap is the result of computer-game marketing 20 years ago

It’s no secret that there is a pronounced gender gap in technology fields. In 2014, 70% of the employees at the top tech companies in Silicon Valley, such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter, were male. In technical roles, this phenomenon is even more pronounced; for example, only 10% of the technical workforce at Twitter is female.

It’s no secret that there is a pronounced gender gap in technology fields. In 2014, 70% of the employees at the top tech companies in Silicon Valley, such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter, were male. In technical roles, this phenomenon is even more pronounced; for example, only 10% of the technical workforce at Twitter is female.

But things haven’t always been this way. The numbers of enrollments among men and women in computer science were on their way toward parity in the 1970s and early 1980s. In 1984, 37% of computer science graduates were women, but those numbers began to drop dramatically in the middle of the decade. By 2016, that number had been whittled down to 18%. This dip in the 1980s has created a chasm that the past 30 years hasn’t been able to overcome—and the dude-centric computer marketing campaigns of that time may be to blame.

Programming is fast becoming the most lucrative skill you can have in the modern world. According to a recent study conducted by Glassdoor, 11 of the 25 best-paying jobs are technology related, with an average earning potential of between $106,000 and $130,000 a year. And this trend is showing no signs of letting up: The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that employment of computer and information-technology occupations will grow by 12% between 2014 and 2024, faster than the average for any other occupation.

However, women will not have the same access to the opportunities presented by this industry. Many of these companies blame the pipeline, citing poor enrollment and graduation rates among women in technology. And they have a point: In states like Mississippi, Montana, and Wyoming not a single girl took an AP-level computer-science examination in 2014.

Marketing games

Although a whole host of factors played a role in this phenomena, Elizabeth Ames from the Anita Borg Institute for Women in Technology believes that one of the primary reasons can be traced back to the close relationship between computing and gaming in the 1980s. “A lot of early computers were used for game playing,” Ames says. “Those games tended to be more aimed more at boys and men, so it was easy for boys to get a leg up in that area through gaming.”

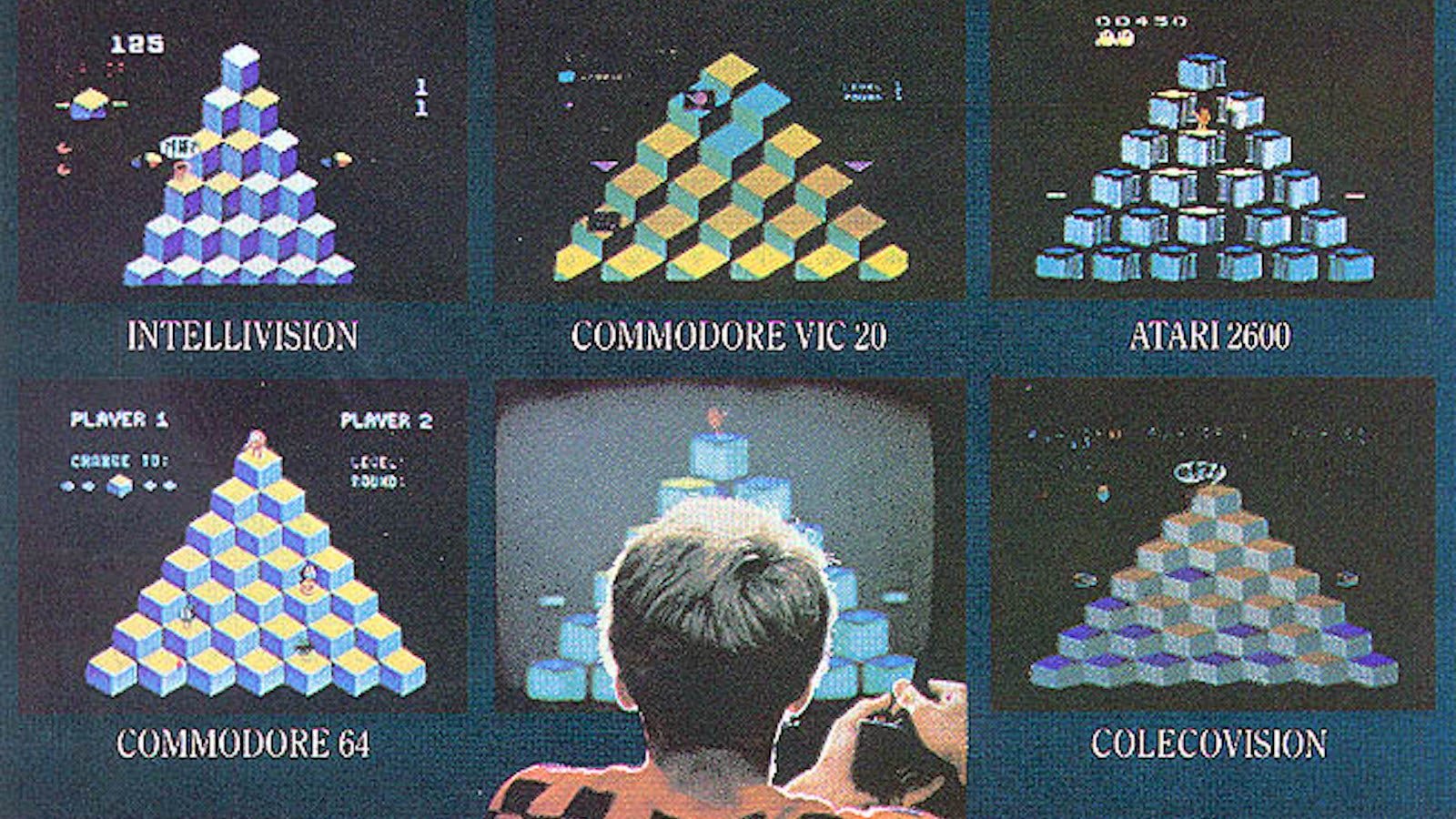

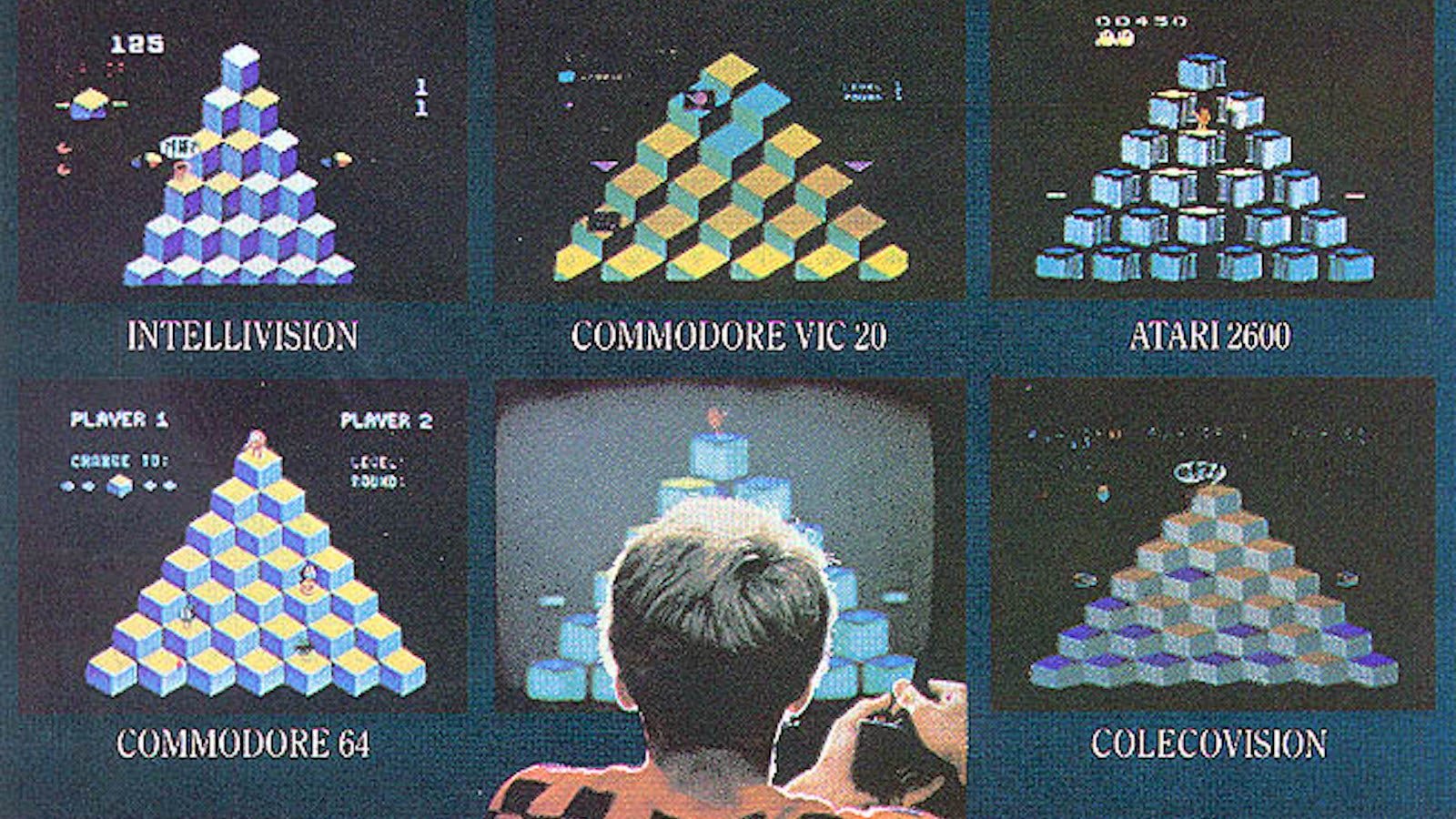

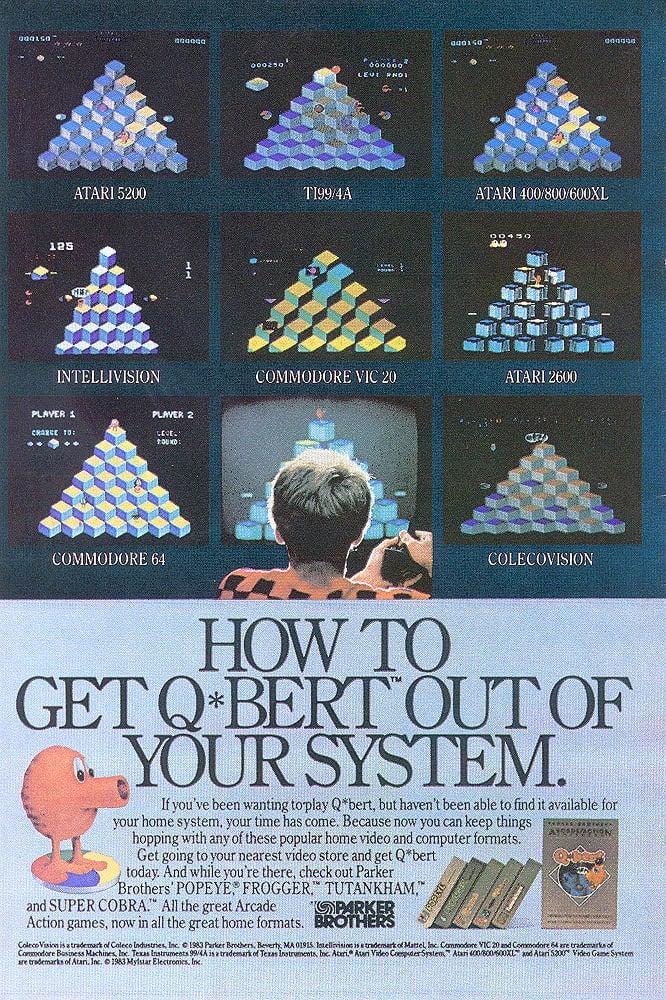

For example, the Apple personal computer that was released at the time was marketed specifically to boys (included them teasing girls’ computer skills), as were a whole range of other consoles. This gave rise to male computing culture. As a result, a 1985 study reported that 73% of men used a computer on a weekly basis, compared to 45% of women surveyed.

This bias toward boys in advertising has a fascinating history in its own right. In 1983, the US experienced a video game recession. The market shrank from $3.2 billion in 1983 to $100 million in 1985, a drop of 97%. The crash was primarily brought about by low-quality games flooding the market, which smothered consumer confidence. Subsequently, marketers trying to rebuild the industry sought to leverage the small audience they had left, which, according to their research, was mostly boys.

From then on, a kind of chicken-and-egg cycle took hold. Advertisers sold games to boys because boys were the ones buying them, and boys were the ones buying them because of the advertisers’ targeted marketing. It’s no coincidence that the console touted to have saved the industry was called a “Game Boy.”

The experience gap widens

This led to what researcher Jane Margolis calls the “experience gap.” In a study she conducted in 1995, she found that among first-year computer-science students at Carnegie Mellon University, 40% of male respondents passed the advanced-placement computer-science exam, meaning they could skip the introductory-level programming class. None of the first year women achieved the same result. Men were also more familiar with programming languages than women and were more likely to report having an “expert” level of programming proficiency before enrolling at Carnegie Mellon. Unsurprisingly, many women opted out of the computer-related courses early.

An American Association of University Women review of more than 380 studies from academic journals, corporations, and government sources found that more early exposure to engineering and computing among boys in school creates “more positive attitudes toward and interest in STEM subjects.” By the time students now reach university, 20% of men plan to take on a career in engineering or computing. Among women, that number is just 5.8%. Women start out so far behind that they often can’t catch up.

Even when women do have considerable experience with coding and mathematics, the male-dominated environment that has arisen becomes an obstacle to entry for many. Professor Linda Sax, a researcher at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, recalls, “I was someone who grew up very confident in my math abilities, but it wasn’t until I went to college that I began to doubt myself.”

Sax says she felt intimidated by the male-dominated culture she encountered at university. She remembers one incident in which she asked the professor a question that he curtly dismissed. A male student asked the same question moments later and got a positive response. “It just felt very isolating,” she says. Sax ended up not completing her degree in programming, choosing a career in quantitative research in education instead.

The few women who do make it into the field are far less likely to stay than their male counterparts. The Center for Talent Innovation, a research think tank, found that US women are 45% more likely than men to leave careers in technology. The research revealed that women often feel isolated due to a lack of female role models and the sense of being excluded from “buddy networks” among men. Once you add in the fact that only 38% of US women get their ideas endorsed by leadership (compared to 44% of men), you soon end up with the scenario in which almost a third of women say they want to quit within the first year.

Though there are isolated examples of both vintage and contemporary computer advertising aimed at women, it is clear that the advertising narrative around women and technology needs to be more inclusive if the gender gap is going to close. Until that happens, as Ames argues, advertising will continue to drive “a subtle message to girls and women that it’s not a place where they belong.”