Scientists figured out why your selfies are funny and authentic but everyone else’s are so narcissistic

You’re at the park, lounging on a colorful blanket that perfectly contrasts with the grass. At a concert, neon lights reflecting off your glistening forehead. In front of the historical monument that subtly displays your love of culture. Or maybe you’re just lying on the couch feeling sexy.

You’re at the park, lounging on a colorful blanket that perfectly contrasts with the grass. At a concert, neon lights reflecting off your glistening forehead. In front of the historical monument that subtly displays your love of culture. Or maybe you’re just lying on the couch feeling sexy.

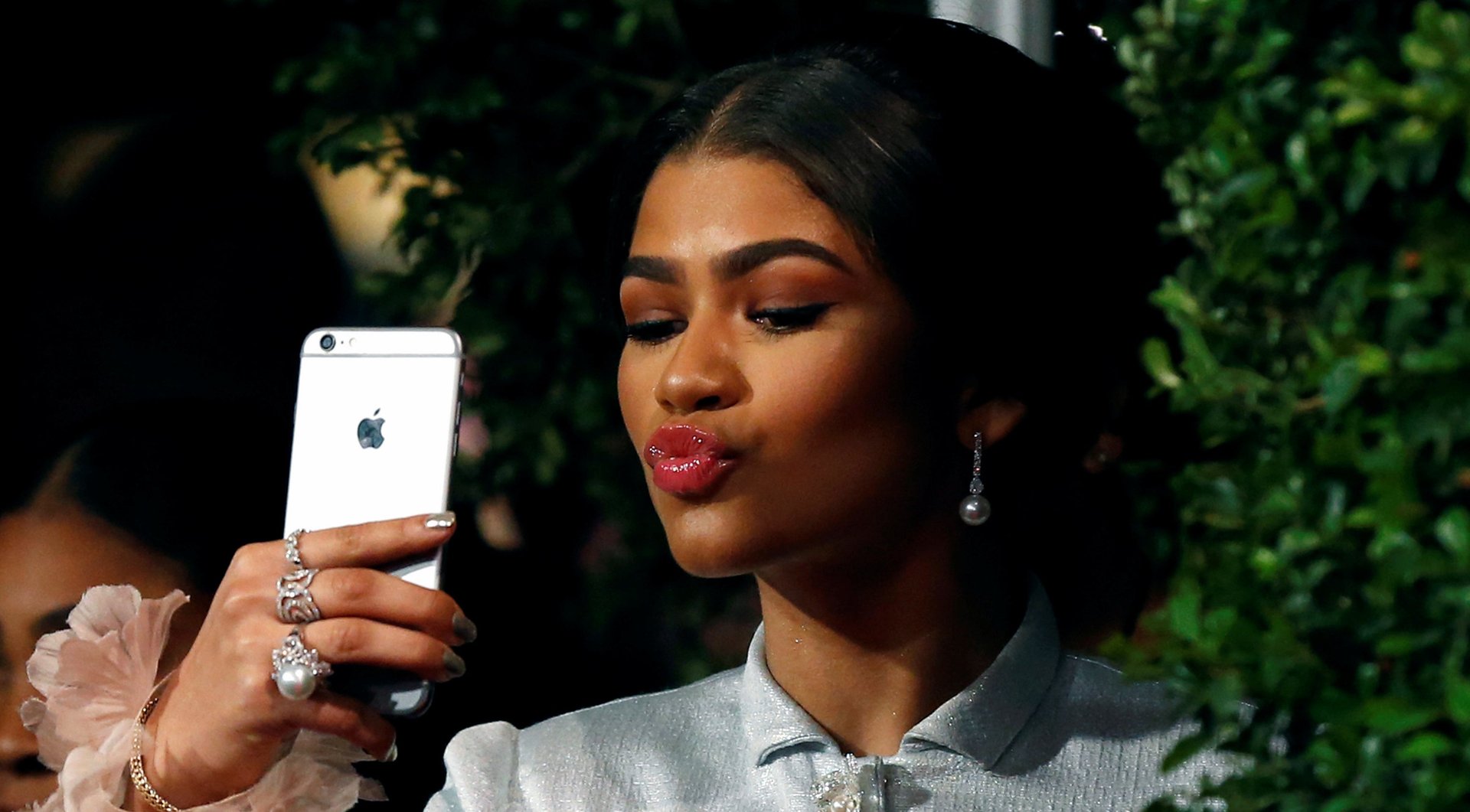

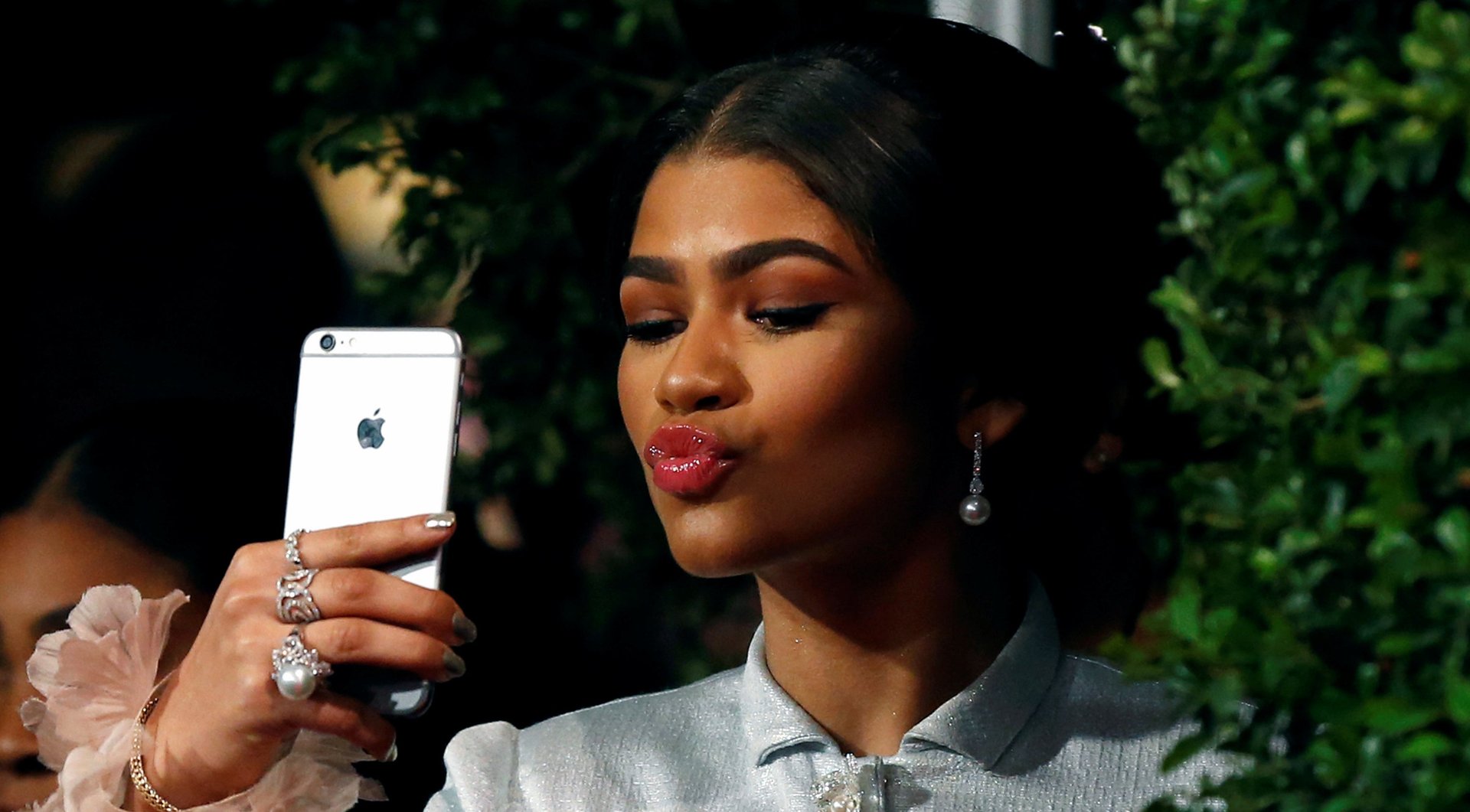

Then it happens: You tussle your hair, extend your arm, smile/smize/duck-face/wink, and snap a selfie. It’s blurry. You snap again. Once more. Yes, that’s golden. You delete the ugly ones and post the cutest take with a breezy or self-deprecating caption: “Just another day at the park!” or “Nothing better than a night in!”

Don’t say you haven’t done it. According to Google statistics, about 93 million selfies were taken per day as far back as 2014, and on Android devices alone. One poll found that every third photo taken by those aged 18 to 24 is a selfie. You take selfies, I take selfies, we all take selfies.

Even so, according to a new study by German researchers in Frontiers in Psychology, most of us would prefer to never see a selfie again. While 77% of the 238 people surveyed regularly took selfies, 62-67% believed that there’s some potential negative consequences of selfies, such as damaged self-esteem, and 82% of participants said they would prefer to see more normal photos and less selfies on social media.

The key to this “selfie paradox” is selfie-perception: Participants consistently rated their own selfies as self-ironic and authentic, while they nearly always (90% of the time) declared others’ selfies self-presentational and superficial. (They also assumed others were having more fun than they were while taking selfies.)

This paradox is explained by a simple psychological theory dating back to the early 1970s: the self-serving bias, an ego-based attribution. “We naturally try to explain our behavior in terms that flatter us and put us in a good light,” says Sarah Diefenbach of Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich, the study’s co-author. “Self-presentational motivations may be associated with narcissism and regarded as less reputable, and therefore attributed to others rather than to oneself. For oneself, one prefers relations to be more reputable character traits such as self-irony or authenticity.”

It’s not all bad: Self-presentational motivations can also actually help personal development, says Pamela Rutledge, director of the nonprofit Media Psychology Research Center. She argues that “aspirational” selfies, or those intended to present one’s “best self” aren’t just about gathering “likes”—they’re also actually an effective way for people to see a path toward behaviors and attributes they desire for themselves.

“Posting high points in life increases confidence, empowerment, gratitude, and appreciation through mindfulness, and the ability to visualize desired outcomes,” says Rutledge.

Ultimately, it shouldn’t be so surprising that we presume our self-shot photos are ironic and genuine, while others roll their eyes. And yet we generally don’t realize we’re being hypocrites.

So next time you see a friend contorting her features into a selfie face, check the snark. After all, that selfie may help her become her “best self.” And that could mean a “like” on your next selfie.