Today marks the 75th anniversary of one of the most brutal executive orders in US history

On Feb. 19, 1942, then-US president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order 9066 authorizing the relocation of all persons considered a threat to national defense from the west coast of the United States inland.

On Feb. 19, 1942, then-US president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order 9066 authorizing the relocation of all persons considered a threat to national defense from the west coast of the United States inland.

These threatening people were, for the most part, Japanese Americans, against whom growing hostility had exploded after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Roughly 90% of American-born Japanese and Japanese-American citizens lived along the west coast at the time, about 125,000 people. Those pushing for their removal, and the creation of internment camps, argued that people of Japanese ancestry were likely to conspire against the US if Japan invaded the Pacific coast.

Life before the executive order was already extremely difficult for Japanese Americans in the US, who faced racism and resentment over their economic success. In 1907, they were banned from getting American citizenship. Immigration from Japan was halted in 1924. Japanese immigrants struggled to settle in white neighborhoods, where signs encouraged them to “keep moving.”

Greg Robinson, professor of history at l’Université du Québec in Montreal and author of By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans said that a number of wild rumors were circulated by people and the press about America’s Japanese population in the months after the Pearl Harbor attack (in what he calls “the fake news of the time”), including that they were conspiring against the US military.

In reality, these suspicions were rooted in racism and jealousy rather than military strategy, Robinson explains. Japanese-Americans not only looked different from white Americans, but most of them were Buddhist rather than Christian, making them stand out even more than other migrants. They had also amassed quite a bit of wealth in the US; taking rather barren lands along the Pacific coast—particularly in California and Washington state—and turning them into highly productive farms, generating complaints by the locals that they worked “too hard,” according to Robinson.

The war against Japan was exploited as an occasion to act upon the racism, and military leaders, with popular support, started advocating the removal of Japanese-Americans from the Pacific coast, with the pretext that a Japanese invasion would get the support of people of Japanese ancestry.

Though the Department of Justice deemed the measure unnecessary, Robinson says that Roosevelt’s own anti-Japanese bias, combined with a desire to not contradict his military leaders during wartime, led to the executive order. Though not explicitly mentioned, Japanese were the main target group by virtue of their location.

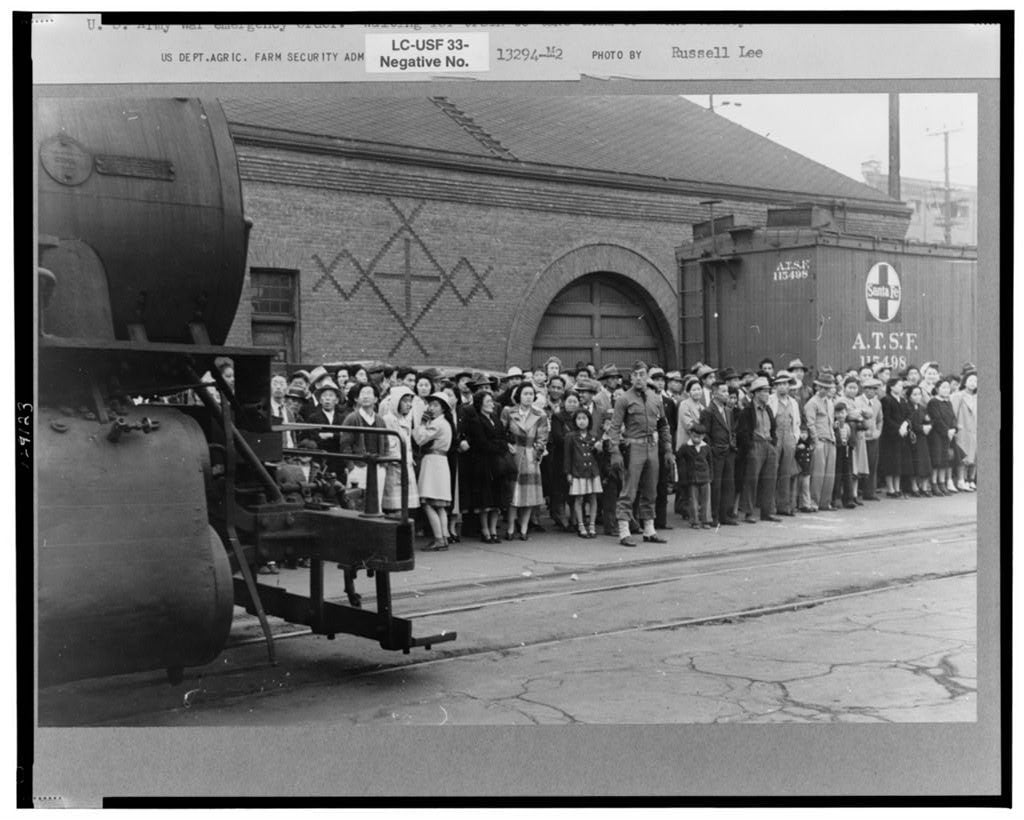

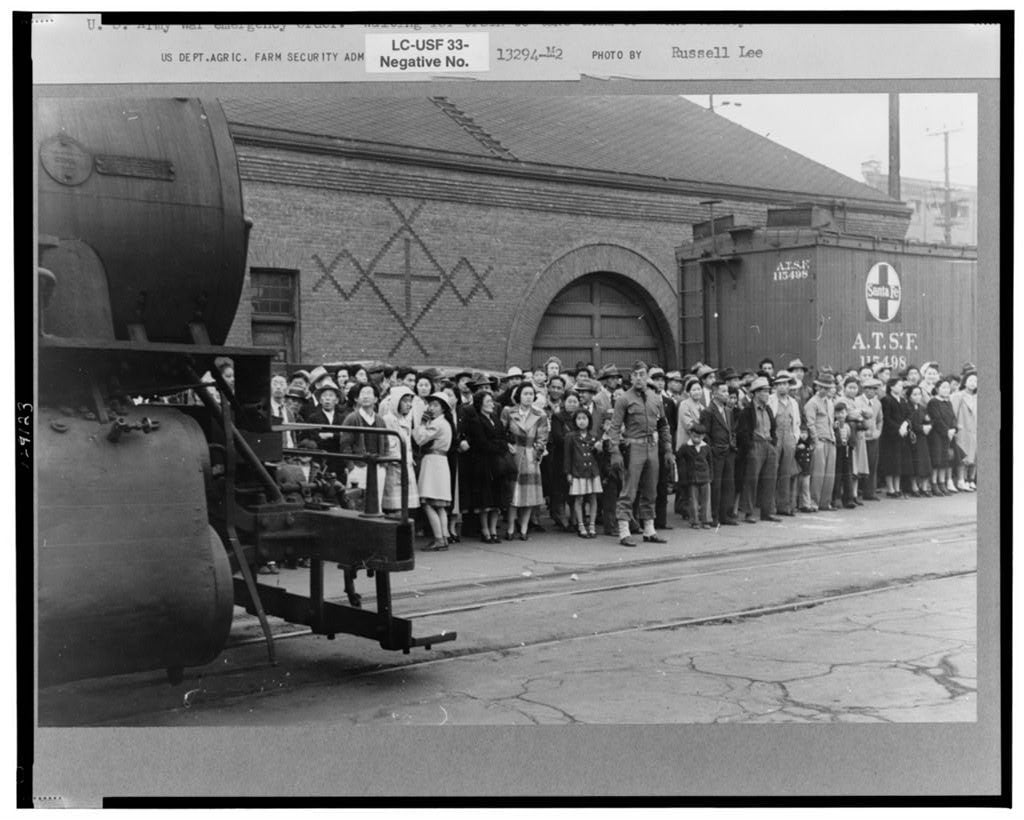

Beginning on March 2, 1942, as the order prescribed, people that ostensibly posed a threat and resided in two military zones corresponding to the parts of the Pacific coasts with the highest Japanese populations were expected to voluntarily hand themselves in a sign of their patriotism. When this failed to produce the desired results, the military began to deport west coast residents of Japanese ancestry at assembly centers to hastily built detention centers in remote parts of the western United States and Arkansas.

With the exception of a tiny number of Japanese women married to white men, the process was ruthlessly efficient, with most of the Japanese population interned within months. Detainees were only allowed to keep what they could carry with them in the assembly centers.

Conditions in the camps were harsh. Each family was assigned only a room, and all adults were forced to work—primarily to build war supplies—for abysmal pay. Only a few people tried to avoid deportation (one man even attempted surgery to mask his heritage) or escape. While the Japanese community was largely compliant with the orders, the camps were often the site of riots and strikes.

A number of Latin American, German, and Italian prisoners were also deported to the camps, but unlike the Japanese, they were arrested after being charged with suspicion of treason or conspiring with the enemy and tried. Robinson says the Supreme Court heard a couple of cases related to the deportations at the time. It ruled that people couldn’t be held indefinitely, but never ruled on the constitutionality of executive order 9066.

Only at the war’s end, three years later, were Japanese Americans allowed to return to their homes. The conditions they returned to were much worse than those they had left. By 1947, half of the detained population was back home, but they faced increased discrimination, and weren’t compensated for their losses, which included farmland. With limited opportunities, they often had to resort to inadequate housing and employment below their education level.

The consequences of the internment were felt for years. Generations to come were deprived of the wealth their ancestors had legally built, purely on the basis of racial discrimination. Today, 75 years later, as America once again faces scrutiny for discriminating against a minority, the Japanese internment camps stand as a reminder of the importance of stopping xenophobia before it spirals out of control.