Donald Trump’s absurd war on truth is forcing the media to act like real journalists again

Among the many plot twists introduced by Donald Trump’s administration, add this to the list: Perhaps never before in US history has the mundane machinations of political personalities getting “booked” on cable news been so publicly debated.

Among the many plot twists introduced by Donald Trump’s administration, add this to the list: Perhaps never before in US history has the mundane machinations of political personalities getting “booked” on cable news been so publicly debated.

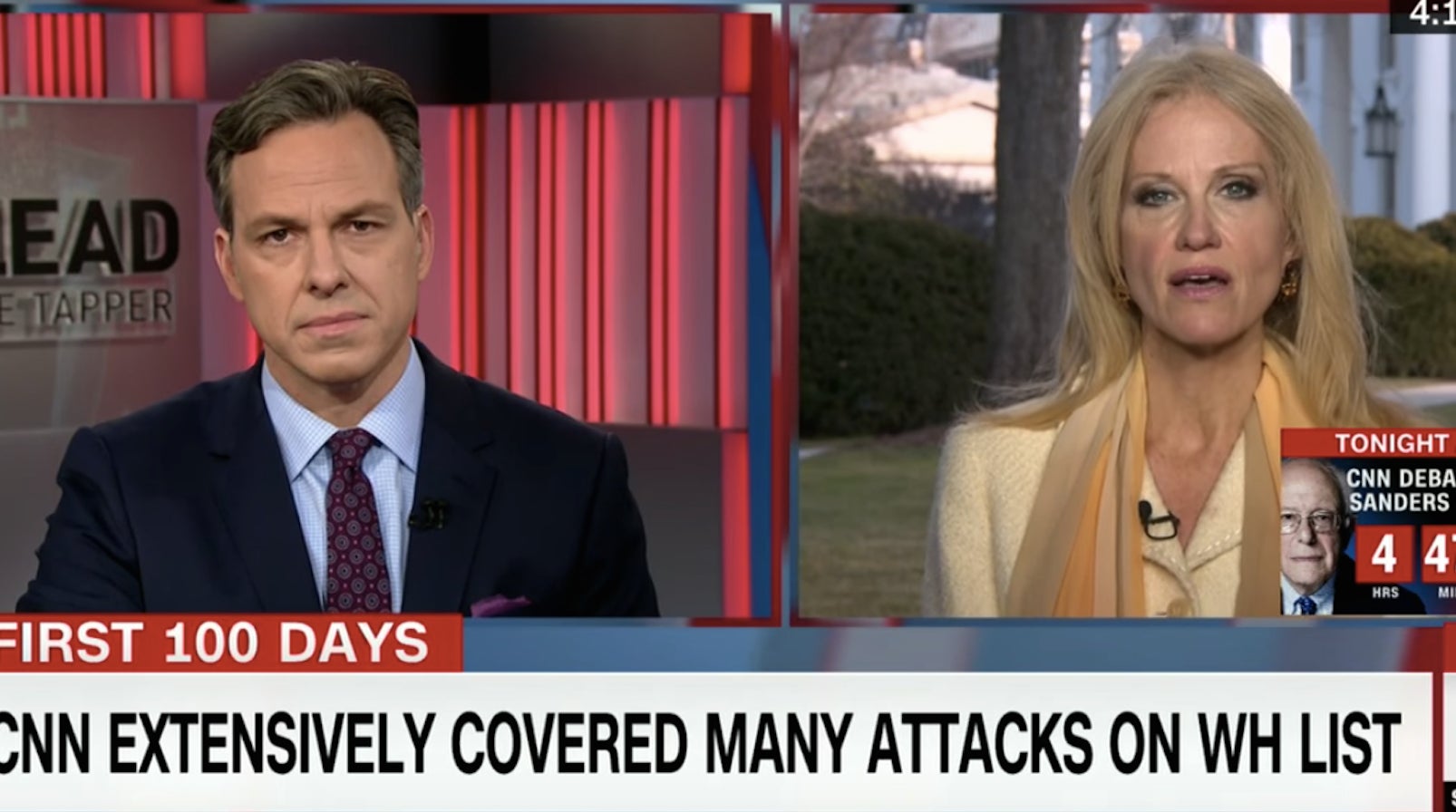

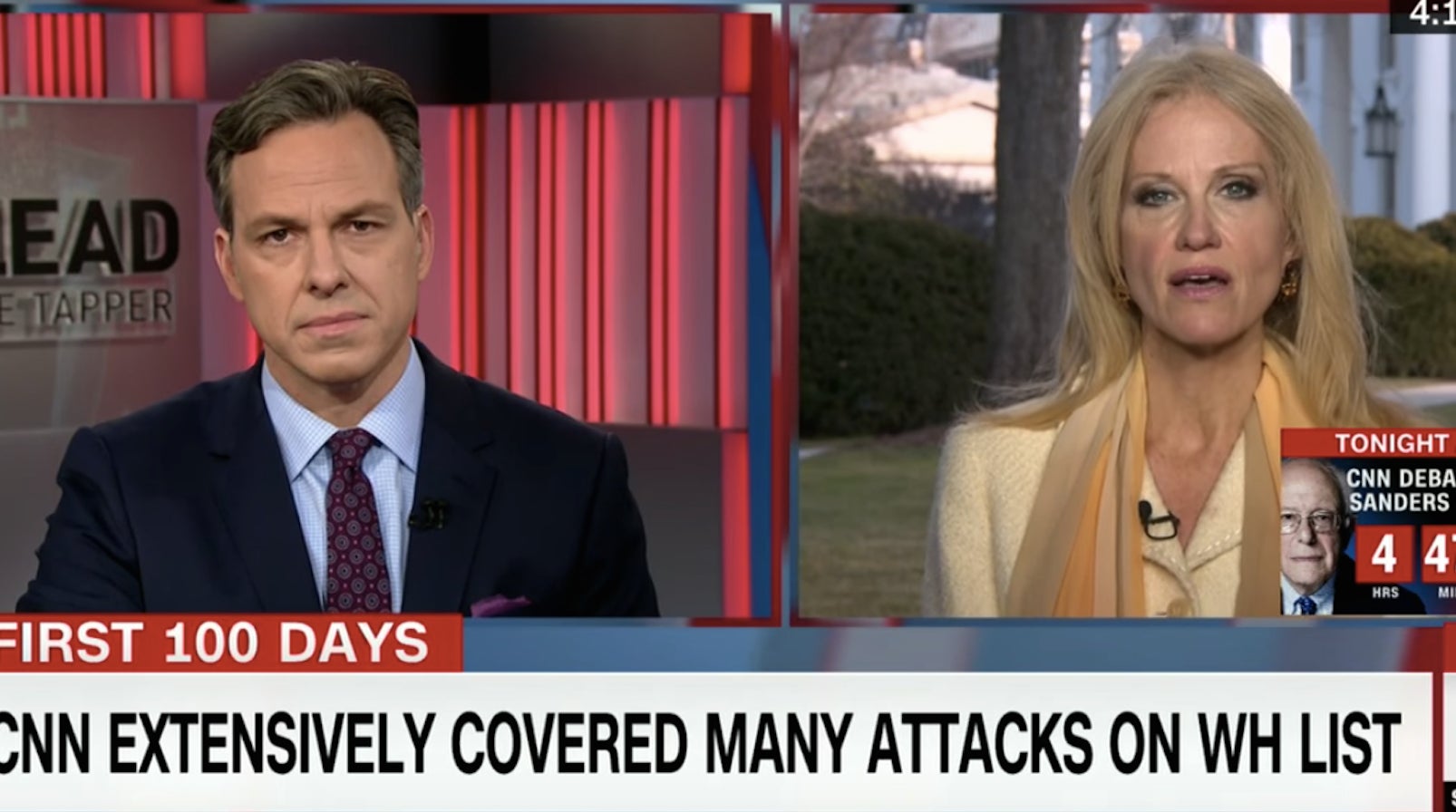

Much attention has been focused on the apparent blacklisting of White House counselor Kellyanne Conway, a frequent face of the Trump team, by some MSNBC and CNN programs that find her, let’s just say, less than truthful. Conway has been accused of “deliver[ing] straight-faced defenses of Mr. Trump’s most outlandish statements and artfully dodg[ing] interviewers’ questions,” and criticized “as an attention seeker who texts TV producers in a constant effort to get on air, so she can speak for a White House where she actually isn’t in the know.”

That the Conway controversy is headline news at all says something important about how relationships between journalists and their sources are changing in the Trump administration—and why this might be a blessing in disguise for American media.

Covering the new administration has given journalists a renewed sense of mission, but the daily dramas, never-ending news cycle, and early-morning presidential tweets are taking their toll. Reporters are energized but also exhausted (by the way, news consumers are, too). The relationship between journalists and the White House they cover has likely never been so fractured—“the Washington political and media establishment [sent] off on a bender seldom, if ever, seen in American history.” And, in CNN’s case, the Trump administration has reportedly banned its officials from appearing on the network (with some exceptions).

Journalists have long relied on key actors in high places to act as sources for their news reports. There’s a mutual motivation involved: Journalists need inside information, and sources want their views to find as broad an audience as possible. Innocuous in theory, in practice this routine can be complicated, and even corrupting. With competition for views fiercer than ever, the news media, especially TV media, is under a lot of pressure to deliver audiences for advertisers. At the same time, insider “access” tempts journalists to compromise their autonomy, allowing sources too much leeway in framing events—or simply in giving “free airtime” to sources who may be offering dubious information but strong ratings.

The relationship between journalists and sources is not, as journalism studies scholar Matt Carlson has pointed out, “a mere exchange of information; patterns of news sourcing confer authority and legitimacy on certain sources or groups while ignoring others. Over time, sourcing routines reinforce notions of who possesses social power.”

And, over time, those routines have reinforced a particular assumption: that political journalism begins from the inside-out, by seeking access to politicians, dutifully reporting their daily briefings, and otherwise staying close to the people in power. If the Trump team is trying to freeze out journalists, perhaps there’s an opportunity to turn the tables—and, in the process, rethink the whole project of political reporting.

Regular access is important, and it has been threatened by Trump’s administration—but, as press critic and journalism professor Jay Rosen has argued, attempting to switch to an outside-in approach might actually make media outlets stronger. This tactic would allow sites to worry less about preserving the routines of White House coverage and focus more on returning to traditional investigative journalism—for example, by starting from the outer rim of government and moving toward the center, developing sources in the federal agencies and civil service corps, “rather than people perceived as ‘players.’”

Such discussions about journalists and access to political sources also serve to distract us from the real issues, which, as many have argued, is exactly what Trump wants. Take the already infamous press conference on Feb. 16, in which president Trump spent the hour viciously attacking the news media. The tactic serves a dual purpose in deflecting attention from more pressing concerns—in this case, Russia and the fallout from the resignation of national security advisor Michael Flynn—while further reassuring and energizing the president’s media-loathing base of supporters. As New York Times reporter Glenn Thrush explained in a series of tweets:

In the Trump administration, this media manipulation is an act of deliberate obfuscation, from “stacking the deck” in press briefings to ensure questions are asked by Trump-friendly conservative media, to deliberately perpetuating false claims, to Trump’s continued cries of “fake news.” As journalist and media critic Tom Rosenstiel explained, “The goal of fake news is not to make people believe the lie. It is to make them doubt all news.”

Yet the news media keep showing up to provide routine coverage of White House press events, and interviewing the same White House surrogates as sources. This has led to intense debate about the journalistic ethics of repeating obvious falsehoods, failing to call out unsubstantiated claims as lies, and including Trump spokespeople as frequent guests on news shows. With criticism mounting, why do media outlets keep doing the same things?

For 24-hour cable news channels, at least, giving such airtime attracts audiences, which is a vital (if problematic) element to an advertising-based business model. CNN’s ratings are up 51% year-over-year. White House press secretary Sean Spicer, for example, has been referred to as “daytime TV’s new star,” as his news briefings average 4.3 million viewers via cable news. Media literacy professor Dan Gillmor recently called this ratings game a “shameless” media move:

And it’s playing directly into Trump’s reality television playbook: provocations, bluster, and an obsessive preoccupation with ratings.

It’s time for the press to rethink its game plan. Clearly, the current access model is broken. Americans’ trust in the news media appears to be at an all-time low. The Trump administration’s approach puts journalists on the defensive, but it should give them license to experiment for a change—to shake off old routines and bad habits. Journalists might take a cue from an infamous line spoken by presidential candidate Trump himself: What do you have to lose?