I was a stressed-out workaholic. Then I realized that one fear was at the root of my problems

When I was 34, I decided to start seeing a life coach. I had a good career in finance, but I knew I wanted to make a change—and I thought it would help to sort through professional options with a neutral third party.

When I was 34, I decided to start seeing a life coach. I had a good career in finance, but I knew I wanted to make a change—and I thought it would help to sort through professional options with a neutral third party.

Years later, my coach and I laugh about our first encounter. The first thing I said to her was, “There’s never enough time.” I spoke at a frenetic pace, bragging about all my time management hacks. I told her how about how I listened to audiobooks at 2.5 times their natural speed; how I’d created a BlackBerry shorthand language that included the most common English words; how I exercised by plowing through tens of thousands of burpees, praising their efficiency.

“Why are you in such a rush?” she finally asked.

I paused. “We’re all going to die someday, so we better get cracking.”

I’d never admitted that reasoning out loud. But I’d been terrified of my own mortality ever since I was a kid. On that day with my coach, I realized that my relationship with death had been causing a lot of problems—from my workaholic tendencies to the stress and worry that characterized much of my everyday life. With the help of some great mentors, I decided to stop trying to beat death and lean into these fears. I needed to learn how to live with the reality of my—and every living thing’s—ultimate destiny.

Giving up control

Like many goal-oriented professionals, I believed for a long time that I could achieve anything I set my mind to. From a young age, I was taught that if I put in the effort, I’d necessarily achieve a good outcome—whether the task at hand was preparing for the SATs, saving money for a video game console, or training for a marathon. I didn’t yet understand that there’s a big problem with this way of seeing the world. It ignores the crucial element of luck: the factors that are outside our control.

For example, I got promoted twice in succession in 2007 and 2009. It was certainly in part the result of hard work and dedication to my job. But during that two-year span, two other things happened. My company underwent a merger, during which the titles of employees at the two companies were brought in line with one another. And the global financial crisis hit, which led to what’s known in the industry as “battlefield promotions.” The narrative in my head at the time was that I simply had earned these rapid-fire promotions. But if I’m honest with myself, it also helped that I was in the right place at the right time.

My belief in the power of self-determination extended to the way I thought about my body and physical health. Take my longtime obsession with Crossfit. I started this workout program (ahem, joined the cult) four years ago. I loved the way that it encourages competitiveness by distilling each workout into a score—one that represents some amalgamation of burpees, squats, pull-ups and more. Who doesn’t want to “win” the workout each day?

But as time went by, I started to realize that there was something deeper going on. I didn’t just want to do well at Crossfit; I wanted to crush the young twenty-somethings who joined our gym. With some prodding from my life coach, I realized a convoluted narrative in my head: “If I can outwork a 21 year old at Crossfit, then I must not really be physically 37 years old!” By crushing Crossfit, I believed I was somehow adding on an extra 16 years of life expectancy. I still love Crossfit – but going in free of burden of extending my life makes it that much more enjoyable.

Then I learned about the Buddhist concept of impermanence. Buddhism encourages people to understand the temporality of all things, including the reality that everything in the world declines and decays. That’s a gut punch to any Type A person who thinks that outcomes can be controlled via hard work, money, success, and influence. But accepting this makes it much easier to move on with your life. And the concept of impermanence can be extended to various facets of work. NBA coach Phil Jackson understood the impermanence of the Chicago Bulls’ dynasties in the 1990s, which helped him prepare emotionally for their inevitable decline while appreciating the joy as it was occurring. Acknowledging and accepting our inevitable fates enables us to savor the numerous special moments as they occur.

Engaging with the present

A lot of us have difficulty staying in the moment—in part because distractions, in the form of smartphones, are always with us. But humans have been struggling to live in the present for a very long time. Fifty years ago, for example, philosopher Alain Watts wrote in The Wisdom of Insecurity, “It is in vain that we can predict and control the course of events in the future, unless we know how to live in the present. It is in vain that doctors prolong life if we spend the extra time being anxious to live still longer.”

I came to understand that my constant refrain—“There’s never enough time!”—was ironically the biggest time thief of all. My progress toward this realization was helped along by the work of Atul Gawande and BJ Miller—two vocal proponents of palliative care.

Palliative care is a medical approach for patients with terminal disease. Its focus is on maximizing the comfort of patients, and their happiness, during the final period of their lives. It is a striking alternative to the invasive, painful, expensive, and experimental treatments that aim to extend life by any means possible. And, in contrast to the Silicon Valley ethos that aims to beat death, it is all about enjoying life’s last drops.

Reading stories about people receiving palliative care, my mindset started to shift. Under palliative care, a woman dying of lung cancer could still be treated to the thing that brought her the most joy—smoking a cigarette. A patient who loved food, even if they could no longer eat, was wheeled into a kitchen full of delicious smells so that they could savor the aroma. At BJ Miller’s non-profit Zen Hospice Project, a small guest house in San Francisco for those needing end of life care, the focus is not about chasing more time, but instead “reveling in what their remaining time can offer.” It facilitates its guests’ last wishes, such as attending a family wedding or riding a motorcycle for the last time.

As I considered what the end of my life might look like, the brutal contrast between enduring numbing treatments and savoring a few weeks or months’ worth of joy was strangely reassuring. It helped me remember to savor the small joys in life, even when things weren’t going my way—a mischievous smile from my daughter, a funny conversation in the car with my wife, the feeling of accomplishment that I get when I hit “publish” on an article I feel proud of. Paying attention to the present moment this way made it easier in my daily life to avoid hyper-obsessing about the future.

Understanding my motivations

One of my most striking discoveries was the work of the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for his book The Denial of Death. Becker argues that many humans try to transcend death with a heroic “immortality” project, which might be creating a billion-dollar company or a multi-generational family dynasty. “The hope and belief is that the things that man creates in society are of lasting worth and meaning, that they outlive or outshine death and decay, and his products count,” he writes. “They earn this feeling by carving out a place in nature, by building an edifice that reflects human value: a temple, a cathedral, a totem pole, a sky scraper, a family that spans three generations.”

This got me thinking about my own ambitions—particularly those that lined up with traditional societal benchmarks. I started to view all ambition through the lens of attempts to transcend death, which brought a remarkable amount of clarity to my decision-making.

Naval Ravikant, the founder of AngelList, rammed the point home for me. On Tim Ferris’ Podcast, he was asked: “What insight about life have you acquired that seems obvious to you, but not be obvious to anyone else?” He replied,

“I’m not afraid of death anymore. And I think a lot of the struggle that we have in life comes from a deep, deep fear of death. And it can take form in many ways. One can be that we want to write the great American novel, or we really want to achieve something in this world, we want to build something, we want to build a great piece of technology or we want to start an amazing business or we want to run for office and make a difference.”

Reflecting on Ravikant’s words, I realized that the desire to build something that would outlive me was all-consuming: I’d tried to make as much money as possible. I’d wanted to build a great company, just because I thought I had it in me. I wanted to write a book. I wanted to do something—anything—to leave my mark on the world.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. But understanding my motivations helped me keep my ego in check and, more importantly, adjust the bar on what I needed to accomplish to be “successful” in my own mind. It was okay to set my sights on smaller goals. I could start a small business, but I didn’t have to try to be the next Elon Musk. I could focus on writing a book without worrying about how it would be received. And as soon as I came to recognize this, the amount of struggle in my everyday life dissipated.

Recognizing the power of constraints

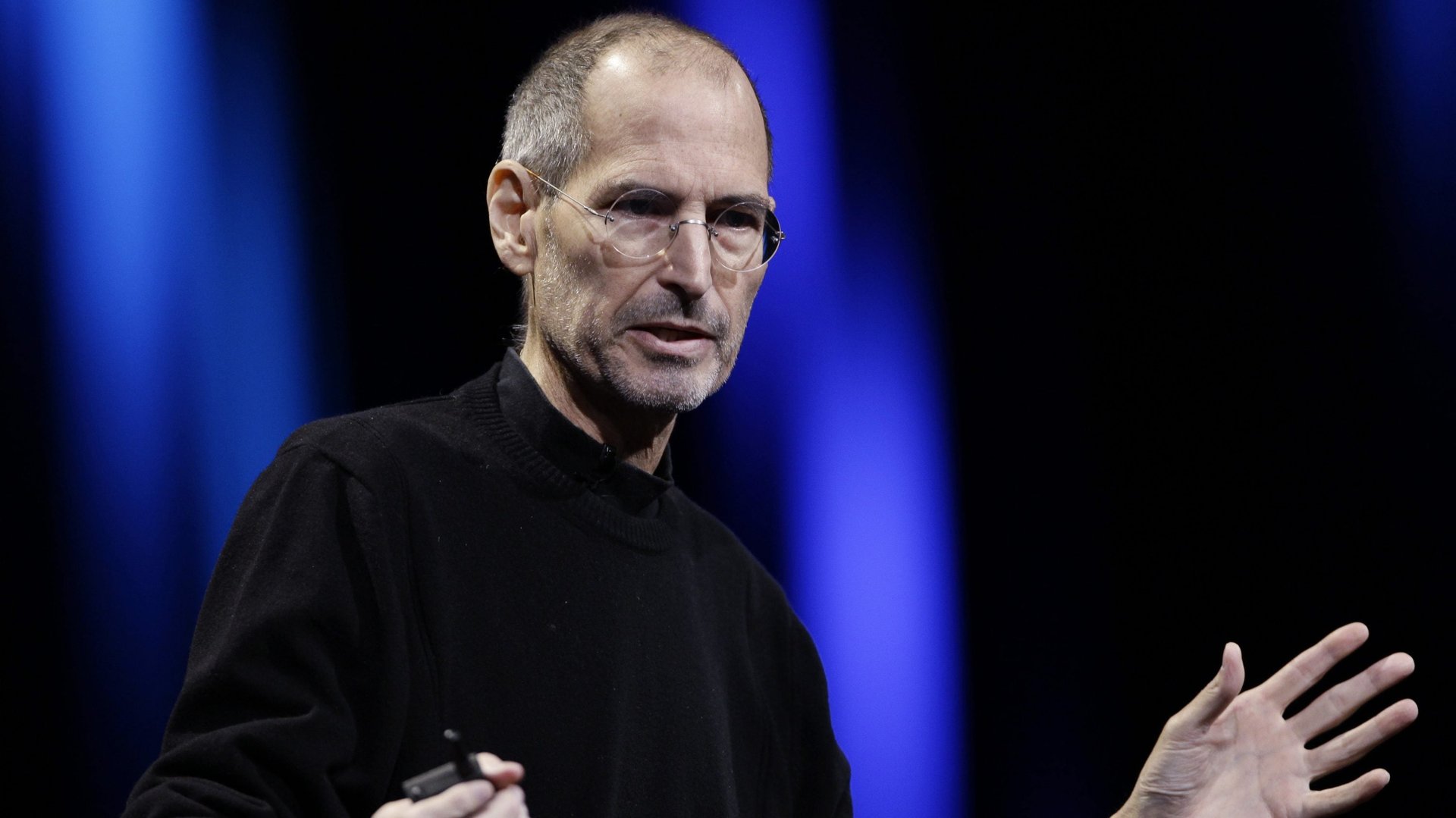

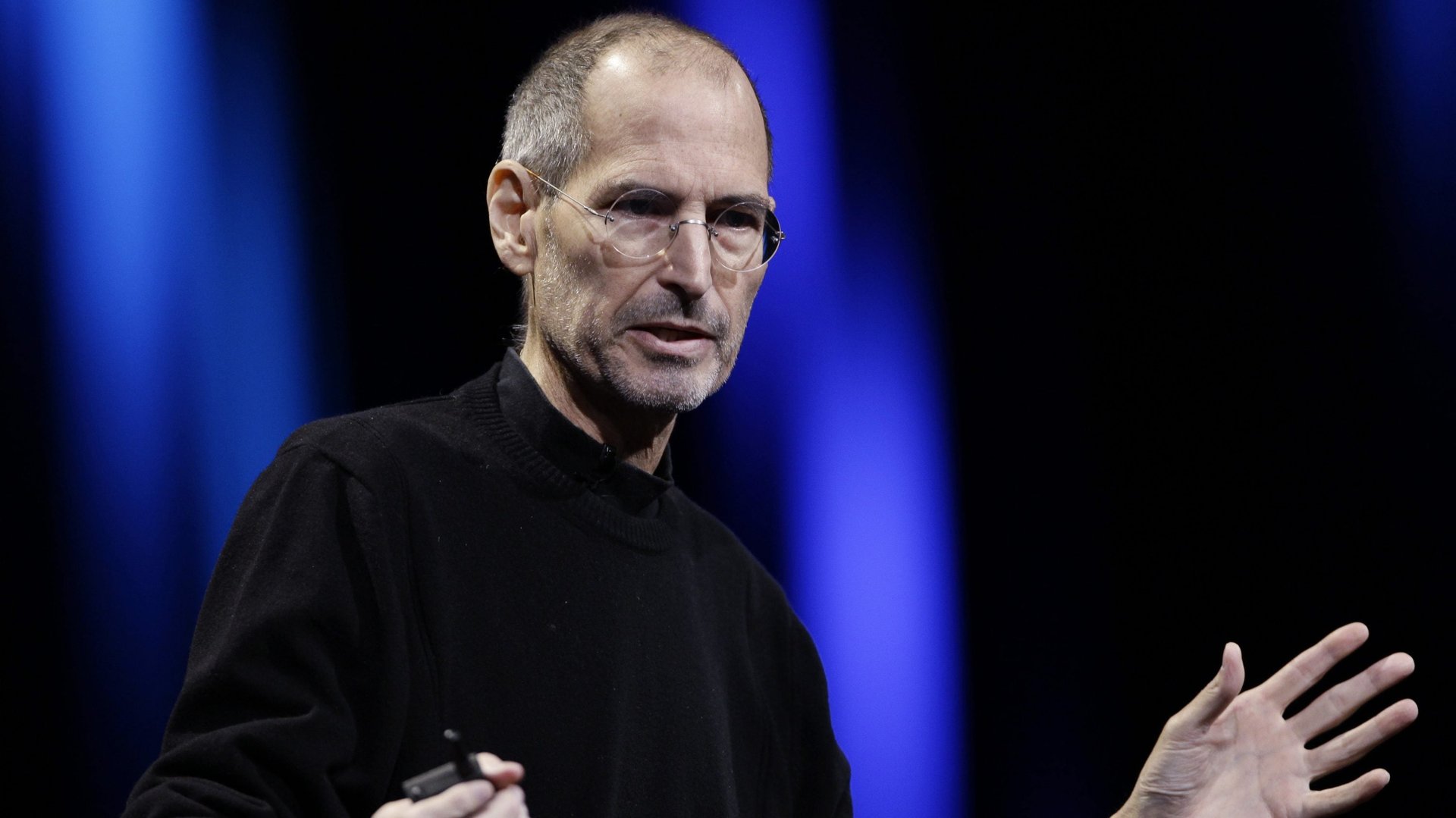

In the language of engineering and product design, death is the ultimate design constraint. Take the first iPhone as an example: Steve Jobs refused to emulate BlackBerry (the competitor at the time) by incorporating a physical keyboard. As a result, Apple had to push the limits of product design, creating a product that was both one-of-a-kind and transformational.

In our own lives, constraints can be similarly empowering. In a famous address at Stanford University in 2005, one year after his cancer diagnosis, Steve Jobs said, “Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life.” In practice, he goes on to explain, this meant asking himself, “If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?” And whenever the answer has been ‘No’ for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.”

Thinking of death this way fundamentally changed the way I perceive professional risk. At a micro level, it keeps me open to experimenting within my career and with my side projects. On a larger level, it shifted my thinking about staying on the corporate treadmill. While leaving the corporate world initially seemed risky, I ultimately realized that not trying my hand as an entrepreneur was—existentially—even riskier.

Looking ahead

As a father, my fears about mortality have taken on a new dimension. Fearing my own insignificance feels downright selfish when there is the burden of giving everything you possibly can to your kids and family. But the most important thing I’ve learned is that the more I reflect on my own death, the less I fear it. I know that I won’t get to decide when my time is up, so instead I focus on the areas I do have power over: healthy diet and exercise, financial prudence, and spending quality time with the people I love.

Talking about death with friends, authentically and vulnerably, has also made a huge difference. This is not exactly a social lubricant for your typical cocktail party. But in more intimate settings, once you start the conversation and realize how many people share this fear, you feel a lot less lonely—and less scared as a result.

I even have a buddy with whom I riff on the topic via email, joking about events that trigger our fear of death and sharing articles and quotes. We call each other “d’homies,” or Death Homies. And it seems there’s a growing hunger in American culture to de-stigmatize death: Death Cafes host informal conversations about our ultimate demise over coffee; a network called The Dinner Party hosts dinners for young people who’ve lost loved ones; and high schools are teaching death ed.

Through my own conversations, I’ve come to understand that my fear of death isn’t exactly what I thought it was. Yes, the infinite nature of time messed with my logical brain. Yes, I’m terrified of losing loved ones. But what I’m really scared of is not having lived a meaningful life. And that’s something I can control.