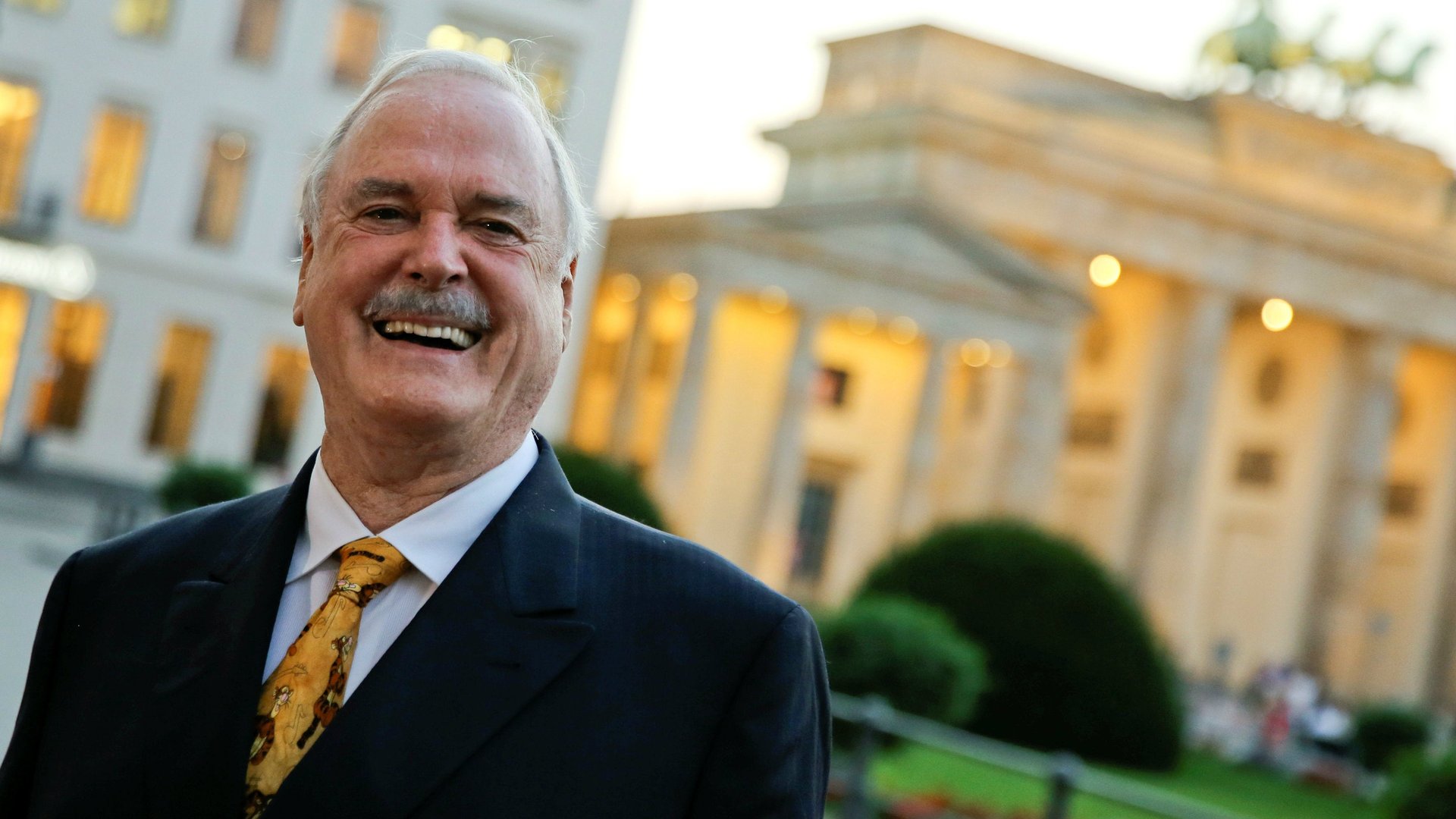

The perfect conditions for creativity, according to Monty Python’s John Cleese

John Cleese is obsessed with creativity.

John Cleese is obsessed with creativity.

He kind of needs to be. He’s the co-founder of Monty Python, the comedy troupe behind Monty Python and the Holy Grail—one of the greatest comedy films of all time.

The group’s impact on comedy was so great that some compare it to the effect the Beatles had on the music industry.

If there’s one thing Cleese is adamant about, it’s that creativity is NOT innate. Creativity is not about genes, he says—it’s about conditions.

I’ve taken the essentials from Cleese’s 1991 lecture on creativity, and organized them into this article.

The moods of creativity

Creativity isn’t about talent. It’s a mood.

Create the right conditions—candles, mistletoe, romantic music—and violin sonatas practically start pouring out of your ears.

According to Cleese, there are two moods we can be in. He calls these moods “modes of operation.”

The first is the closed mode:

By the “closed mode” I mean the mode that we are in most of the time when we are at work. We have inside us a feeling that there’s lots to be done and we have to get on with it if we’re going to get through it all. It’s an active—probably slightly anxious—mode, although the anxiety can be exciting and pleasurable. It’s a mode which we’re probably a little impatient, if only with ourselves. It has a little tension in it, not much humor.

In the closed mode, it is impossible to be creative. Unfortunately, that’s the mode we’ve spent most of our lives in.

The second is the open mode:

The open mode, is a relaxed, expansive, and less purposeful mode in which we’re probably more contemplative, more inclined to humor (which always accompanies a wider perspective), and, consequently, more playful.

It’s a mood in which curiosity for its own sake can operate because we’re not under pressure to get a specific thing done quickly. We can play, and that is what allows our natural creativity to surface.

The open mode lets us play, and play lets us be creative.

Directors like Alfred Hitchcock understood this:

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s regular co-writers has described working with him on screenplays. He says, “When we came up against a block and our discussions became very heated and intense, Hitchcock would suddenly stop and tell a story that had nothing to do with the work at hand. At first, I was almost outraged, and then I discovered that he did this intentionally. He mistrusted working under pressure. He would say ‘We’re pressing, we’re pressing, we’re working too hard. Relax, it will come.’ And, says the writer, of course it finally always did.”

So how do we get to the creative open mode?

Cleese shares five steps.

1. Create a space/time oasis

With the pressures of everyday life, it’s hard to be playful. And no playfulness means no creativity.

The solution, says Cleese, is to create a “space/time oasis”:

You have to create some space for yourself away from those demands. And that means sealing yourself off. You must make a quiet space for yourself where you will be undisturbed.

And it’s only by having a specific moment when your space starts and an equally specific moment when your space stops that you can seal yourself off from the every day closed mode in which we all habitually operate.

Here are some practical steps for implementing that:

- Space oasis. Find a location where you won’t be distracted. This could be a cafe, a library, or a cabin in the woods. Or, it could be your kitchen before the kids get up.

- Time oasis. Find a block of time where you won’t be disturbed. Many famous writers only write in the morning or late at night. Those are the hours where nobody is around to disturb you.

Dig into memoirs and you’ll notice all kinds of successful artists doing this. For example, novelist Murakami Haruki compares writing to the isolation of running.

2. Stick it out

As always, results come from better decisions in difficult times.

I was always intrigued that one of my Monty Python colleagues seemed to be more talented than I was but did never produce scripts as original as mine. And I watched for some time and then I began to see why. If he was faced with a problem, and fairly soon saw a solution, he was inclined to take it. Even though he knew the solution was not very original.

Cleese reacted differently than his colleague:

Whereas if I was in the same situation, although I was sorely tempted to take the easy way out, and finish by 5 o’clock, I just couldn’t. I’d sit there with the problem for another hour-and-a-quarter, and by sticking at it would, in the end, almost always come up with something more original.

My work was more creative than his simply because I was prepared to stick with the problem longer.

The next time you find yourself mentally exhausted, stick it out for a little longer.

3. Make mistakes

Creativity and failure are close cousins.

The very essence of playfulness is an openness to anything that may happen. The feeling that whatever happens, it’s OK. So you cannot be playful if you’re frightened that moving in some direction will be “wrong”—something you “shouldn’t have done.”

Well, you’re either free to play, or you’re not.

So you’ve got to risk saying things that are silly and illogical and wrong, and the best way to get the confidence to do that is to know that while you’re being creative, nothing is wrong.

Nothing will stop you being creative so effectively as the fear of making a mistake.

4. Embrace humor

Sometimes, serious situations (war councils, for example) require creativity. It’s a mistake to think that humor and seriousness can’t go together.

I think we all know that laughter brings relaxation, and that humor makes us playful, yet how many times have important discussions been held where really original and creative ideas were desperately needed to solve important problems, but where humor was taboo because the subject being discussed was “so serious?”

The two most beautiful memorial services that I’ve ever attended both had a lot of humor, and it somehow freed us all, and made the services inspiring and cathartic.

Humor is an essential part of spontaneity, an essential part of playfulness, an essential part of the creativity that we need to solve problems, no matter how “serious” they may be.

Take your creative work seriously? Start giggling.

5. Keep a light hold of it

After you’ve created the conditions for creativity—the open mode—the rest is easy:

The only other requirement is that you keep mind gently ‘round the subject you’re pondering.

You’ll daydream, of course, but you just keep bringing your mind back, just like with meditation. Because, and this is the extraordinary thing about creativity, if you just keep your mind resting against the subject in a friendly but persistent way, sooner or later you will get a reward from your unconscious, probably in the shower later. Or at breakfast the next morning, but suddenly you are rewarded, out of the blue a new thought mysteriously appears.

First, optimize for playfulness—find space and time, push past your limits, make mistakes, and be humorous.

Then, sit back and let the good things happen.

This post originally appeared at Better Humans.