The first American female war correspondent killed in action battled sexism through her life

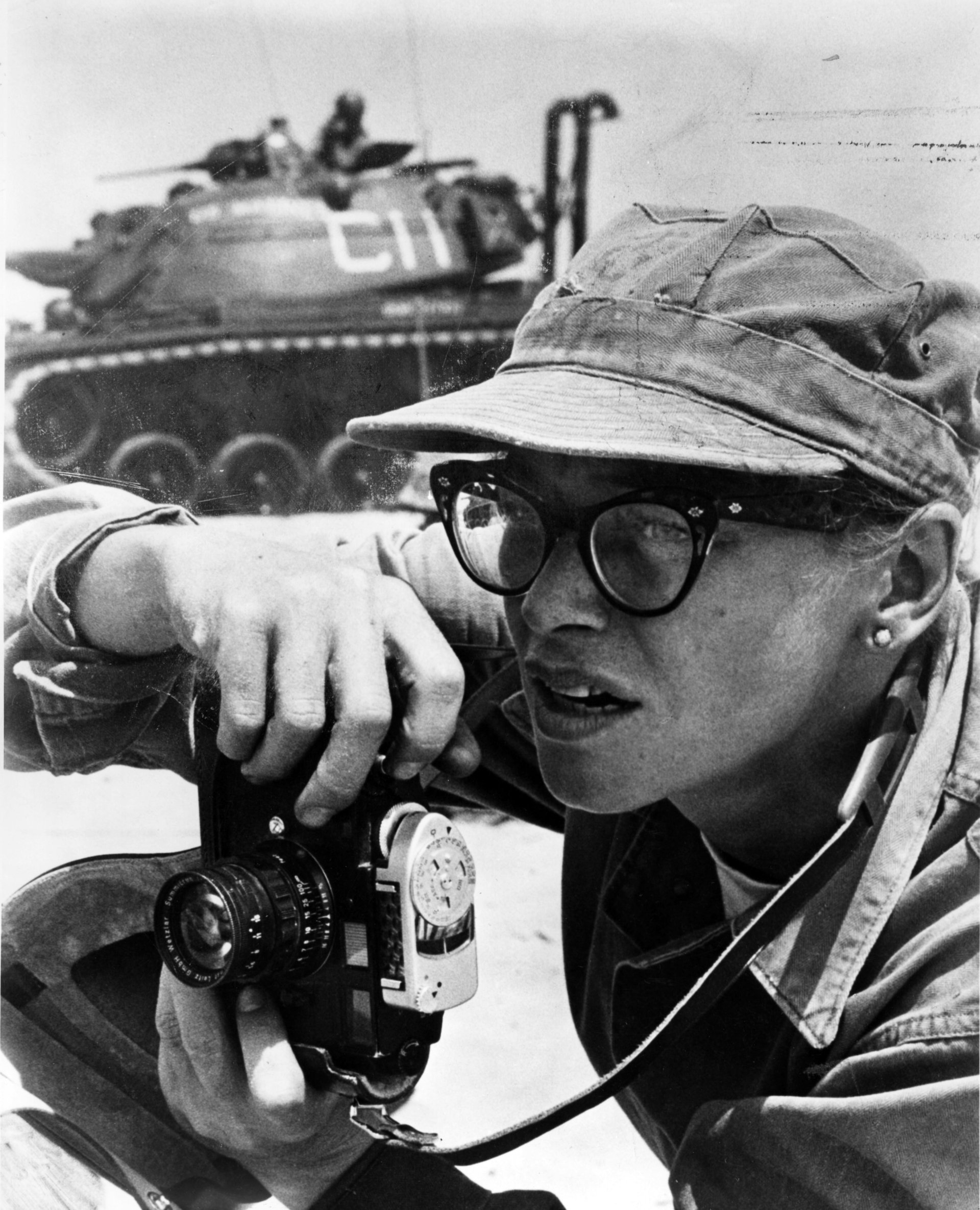

Georgette Dickey Chapelle, a freelance photojournalist and the first American female war correspondent to be killed in action, was a trailblazer. She overcame gender discrimination in her personal and professional life to become one of the very first women on the front lines of war, and one of the most important war photographers of the 20th century.

Georgette Dickey Chapelle, a freelance photojournalist and the first American female war correspondent to be killed in action, was a trailblazer. She overcame gender discrimination in her personal and professional life to become one of the very first women on the front lines of war, and one of the most important war photographers of the 20th century.

Dickey Chapelle Under Fire, a new book by Iraq War veteran and former US Coast Guard Academy professor John Garafolo, explores Chapelle’s work and life through the incredible photographs she took, many of which were once published in National Geographic, Life, and other magazines.

The title of the book comes from a dateline Chapelle wrote from the battlefield of Iwo Jima in 1945. “It was dawn before I fell asleep, and later in the morning I was only half-awake as I fed a fresh sheet of paper into the typewriter and began to copy the notes from the previous day out of my book,” Chapelle writes of that day. “But I wasn’t too weary to type the date line firmly as if I’d been writing datelines all my life: ‘From the front at iwo jima march 5’—then I remembered and added two words: ‘under fire’—They looked great.”

“I admire the fact that she felt her gender should never get in the way of her being able to do her job,” says Garofolo. “She really is a model of persistence.” He added that while many war correspondents at the time moved on to doing other things after World War II ended, Chapelle continued on, much like modern war correspondents who often spend a lifetime covering combat situations.

Chapelle took an unlikely path to journalism. She was born Georgette Louise Meyer in 1919, and grew up in Shorewood, Wisconsin, a suburb north of Milwaukee. She was captivated by aeronautics and at 14, wrote an article for the United States Air Service magazine entitled “Why We Want to Fly.” A year later, she met Admiral Richard “Dickey” Byrd when he spoke at her high school, and the meeting inspired her to change her name to Dickey. At 16, she won a full scholarship to study aeronautical engineering at MIT—which was nearly unheard of for a young woman in the 1930s.

While at MIT, she wrote an article about the Coast Guard and sold it to the now-defunct newspaper Boston Traveler. She was hooked. She started spending all her time hanging out at the Coast Guard base and the Boston Navy Yard looking for stories—it got so bad, she failed out of college after two years.

Her parents sent her to live with her grandparents in Florida where she found work writing press releases for a local air show. Her work took her to Havana where she happened to witness a Cuban pilot die in a plane crash during a popular air show. She rushed to a pay phone and landed a story in The New York Times.

Her hustle landed her a job at Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) in New York City, where she met Tony Chapelle, a photographer at TWA who gave her lessons. They began dating and married in 1940. With his help, she compiled a portfolio of photographs and sold her first photo essay to Look magazine in 1941. That year, when the US entered World War II, Chapelle began her journey as a war correspondent.

“I grew up in the heartland of the United States. I believed that I could do anything I really wanted to do and I still believe it,” said Dickey Chapelle, as cited by Roberta Ostroff in her 1992 biography of the photographer, Fire in the Wind. “Nowhere else in the world can a woman of 17 or an old lady in her 40s as I am, say ‘I can do anything I want to do.’ But I am going to condition it. You can do anything you want to do if you want to do it so badly you’ll give up everything else to do it.”

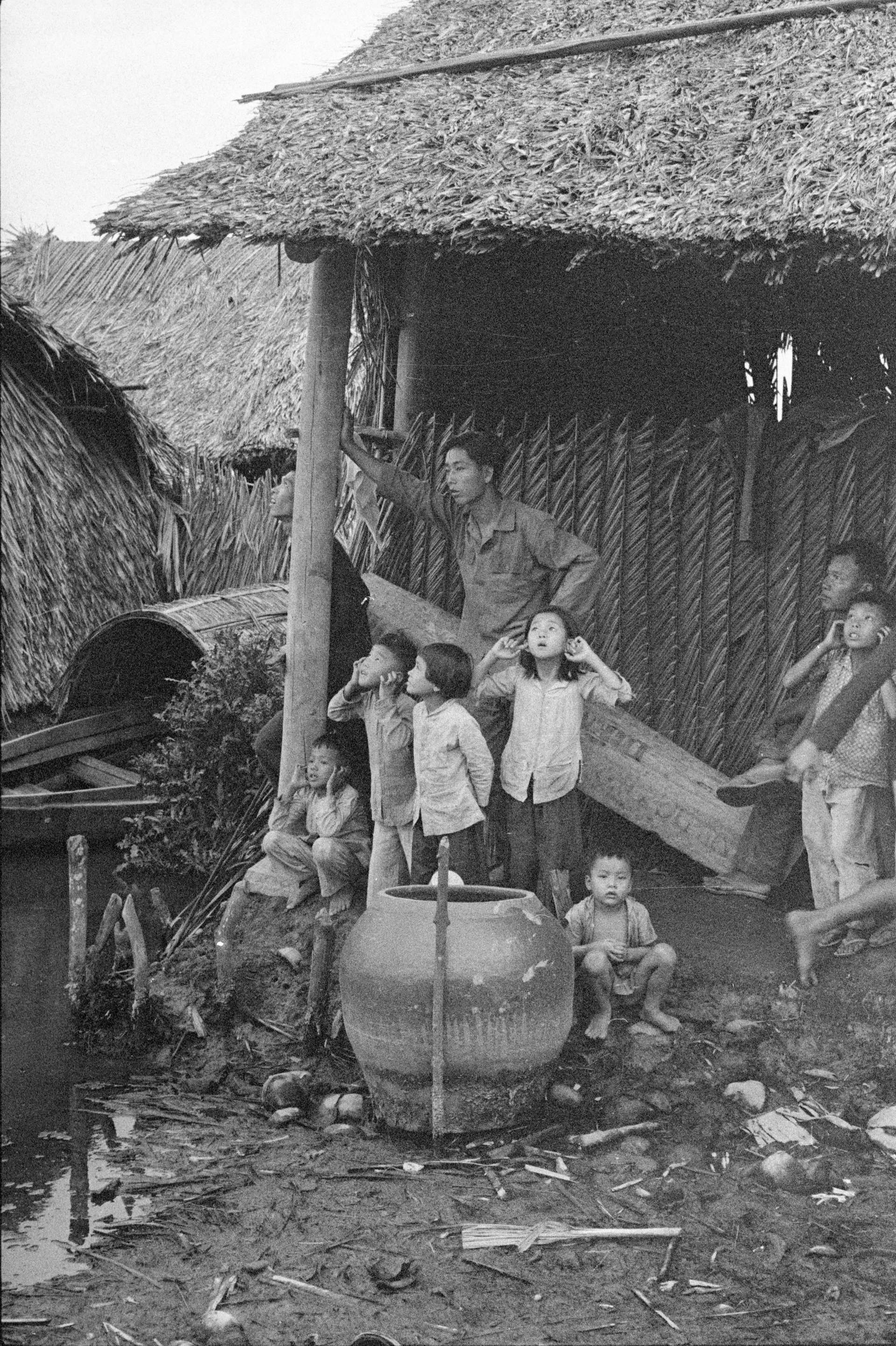

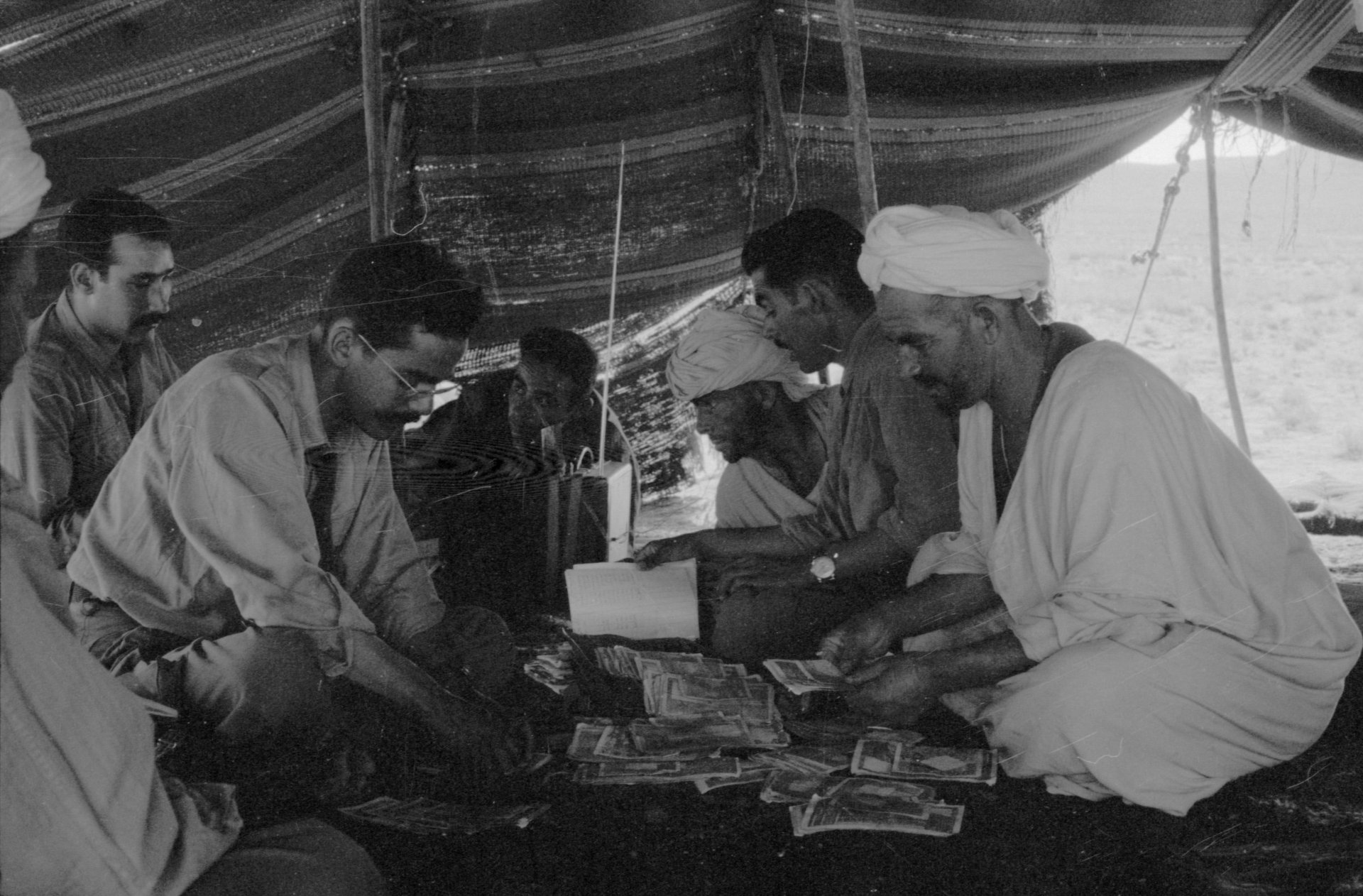

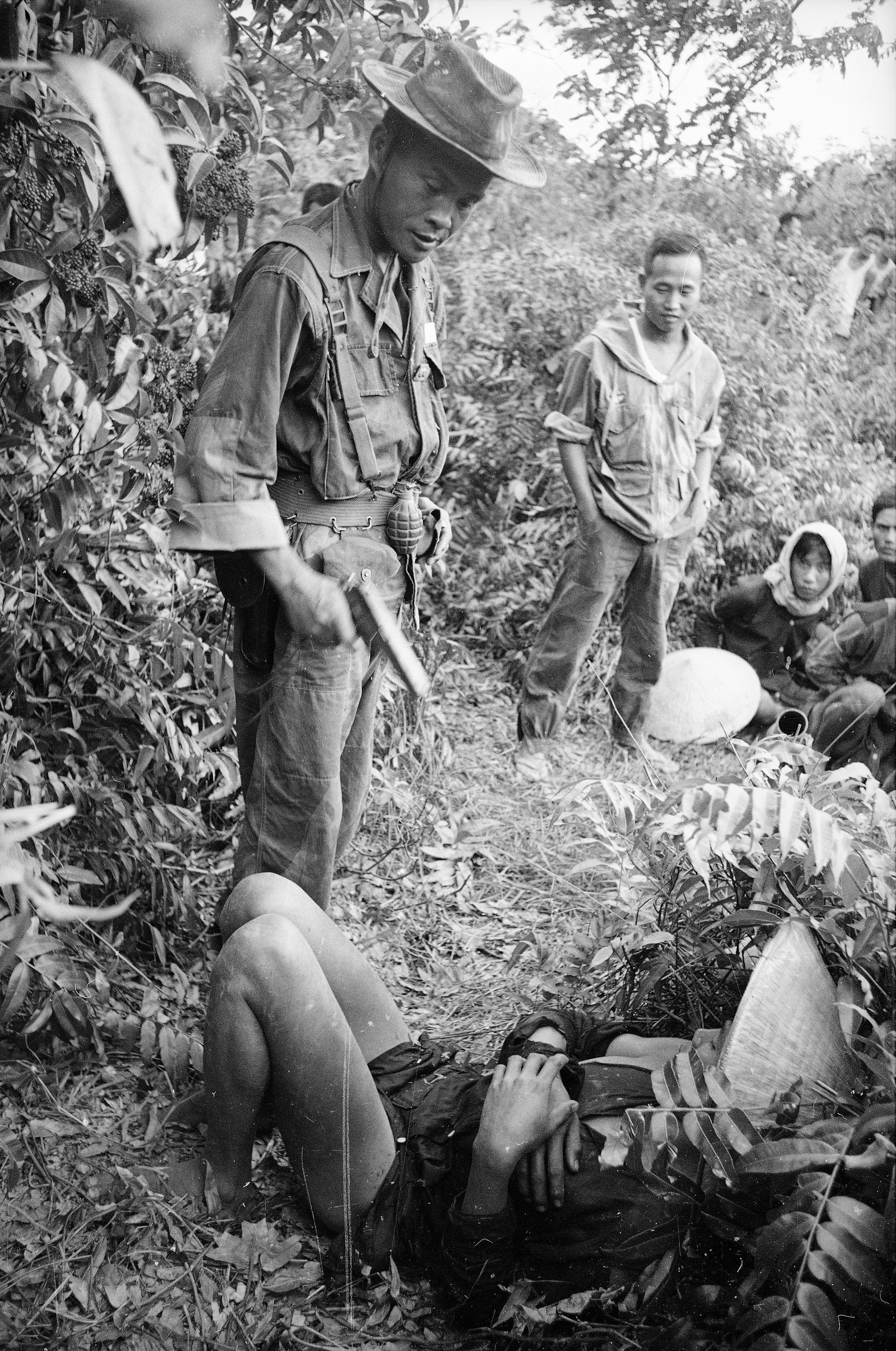

Chapelle covered conflict at a time when most editors did not send women to war zones. She convinced the Navy to allow her cover the front lines in the Pacific theater of World War II, and ended up covering the deadly battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Later, she accompanied Fidel Castro in the jungles of Cuba; was smuggled into Algeria by rebels to cover their side of the story in the war with France; and made parachute jumps into conflict zones of Korea, Vietnam, the Dominican Republic.

In 1956 she was imprisoned for two months in Hungary, and escaped likely execution by stuffing her tiny camera into a glove and tossing it out the window on the way to an interrogation. Over the years, she reported from Japan, India, Jordan, Iran, Iraq, Cuba, Algeria, the Dominican Republic, Lebanon, Korea, Laos, and Vietnam.

“The wreckage resulting from man’s inhumanity to man—whether from the time of Ghengis Khan or Adolph Hitler—was the litany I wrote and the subject I photographed,” wrote Chapelle in her autobiography, What’s a Woman Doing Here? “And the magnitude of relief devised never matched the magnitude of the suffering caused.”

Yet she continuously faced sexism at her job, at a time when few women were sent to cover battlefields. The women who did faced red tape, condescension, disdain, and even outright hostility.

“Get that broad the hell out of here!” a US Marine Corps general said to Chapelle, who was covering his front during the battle of Okinawa, toward the end of World War II. One common excuse used to deny women permission at a base was the lack of bathroom facilities for women. One general told Chapelle that he did not want 100,000 Marines pulling up their pants because she was around. “That won’t bother me one bit,”‘ she replied. “My object is to cover the war.”

But perhaps worse was the gender discrimination she endured in her personal life. Her husband Tony was also a photographer, and while they often collaborated, sometimes they found themselves competing for the same jobs. Through her career, Chapelle made it a point to try to never earn more than her husband, to protect his ego. “I never looked for a job if I thought it was one Tony would have wanted, telling myself it wouldn’t be considerate to get a bigger income than Tony,” said Chapelle, according to Ostroff’s 1992 biography.

In 1953, Chapelle and her husband returned to New York and shortly after, she discovered he was having an affair. The couple parted ways, “both personally and professionally.” After their divorce, she wrote about how often, over the course of her career, she had been asked how to balance her marriage and work. “Several times, television interviewers and people who hear me lecture have asked me the same question about marriage,” she said. “’Can a woman be both a foreign correspondent and a wife?’ My answer: never at the same time.”

In 1962 she was interviewed by a young Mike Wallace on his radio show and he asked her whether being at the front lines of war was a “woman’s place”. “It is not a woman’s place,” she responded. “There’s no question about it. There’s only one other species on earth for whom a war zone is no place, and that’s men. But as long as men continue to fight wars, why I think observers of both sexes will be sent to see what happens.”

Chapelle was killed by a mine while on patrol with US Marines outside Chu Lai in Vietnam on Nov. 4, 1965. Photographer Henri Huet of The Associated Press captured an image of a Navy chaplain delivering Chapelle’s last rites.

A day later, general Wallace M. Greene Jr., the commandant of the Marine Corps, released a message: “She was one of us and we will miss her.”