Trump’s “fake news” playbook is ripped straight from the pages of a 180-year-old media hoax

The Aug. 25, 1835 issue of the New York Sun carried astonishing news. From the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, where he’d traveled to study the southern skies, English astronomer John Herschel had discovered life on the moon.

The Aug. 25, 1835 issue of the New York Sun carried astonishing news. From the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, where he’d traveled to study the southern skies, English astronomer John Herschel had discovered life on the moon.

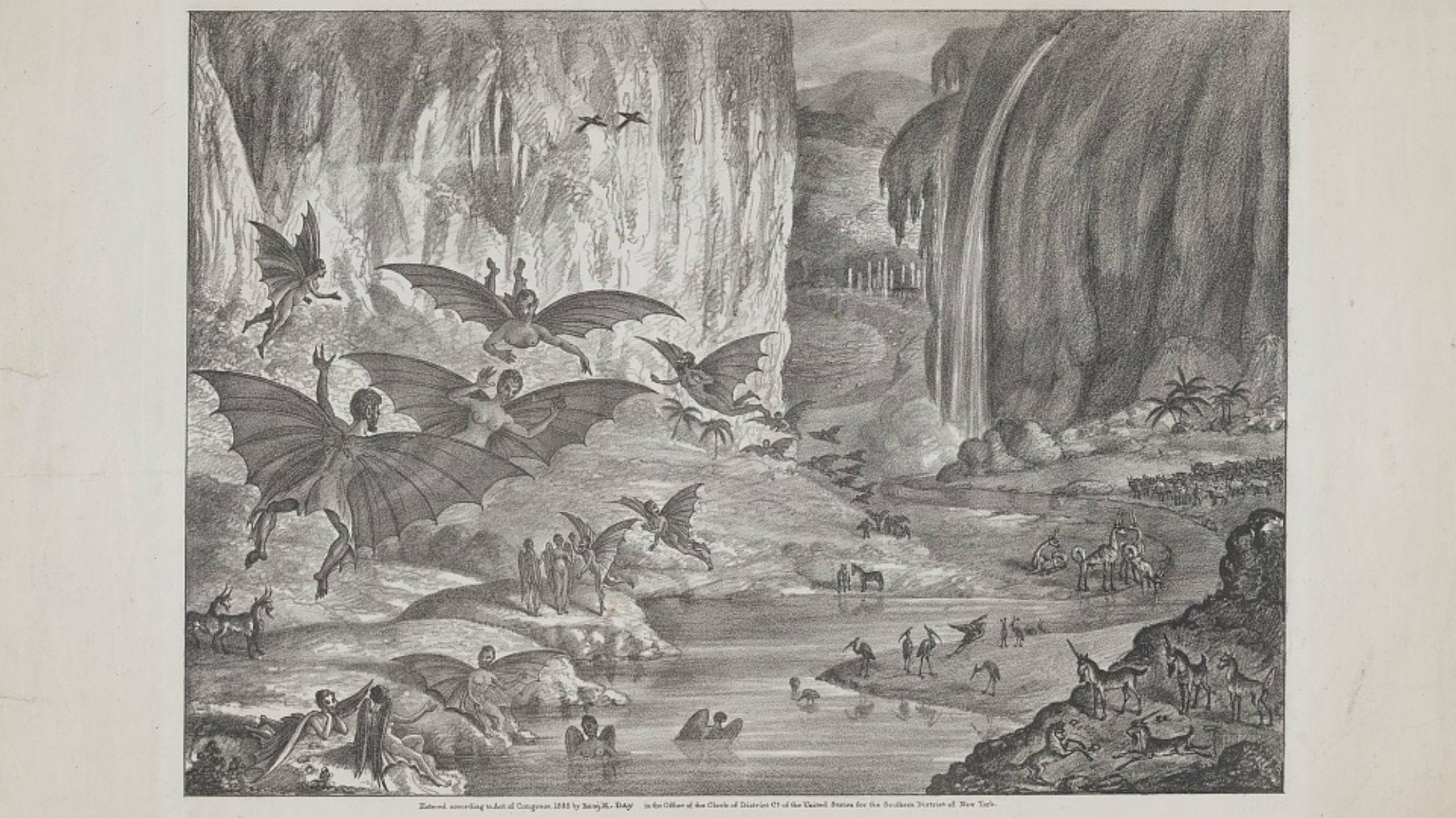

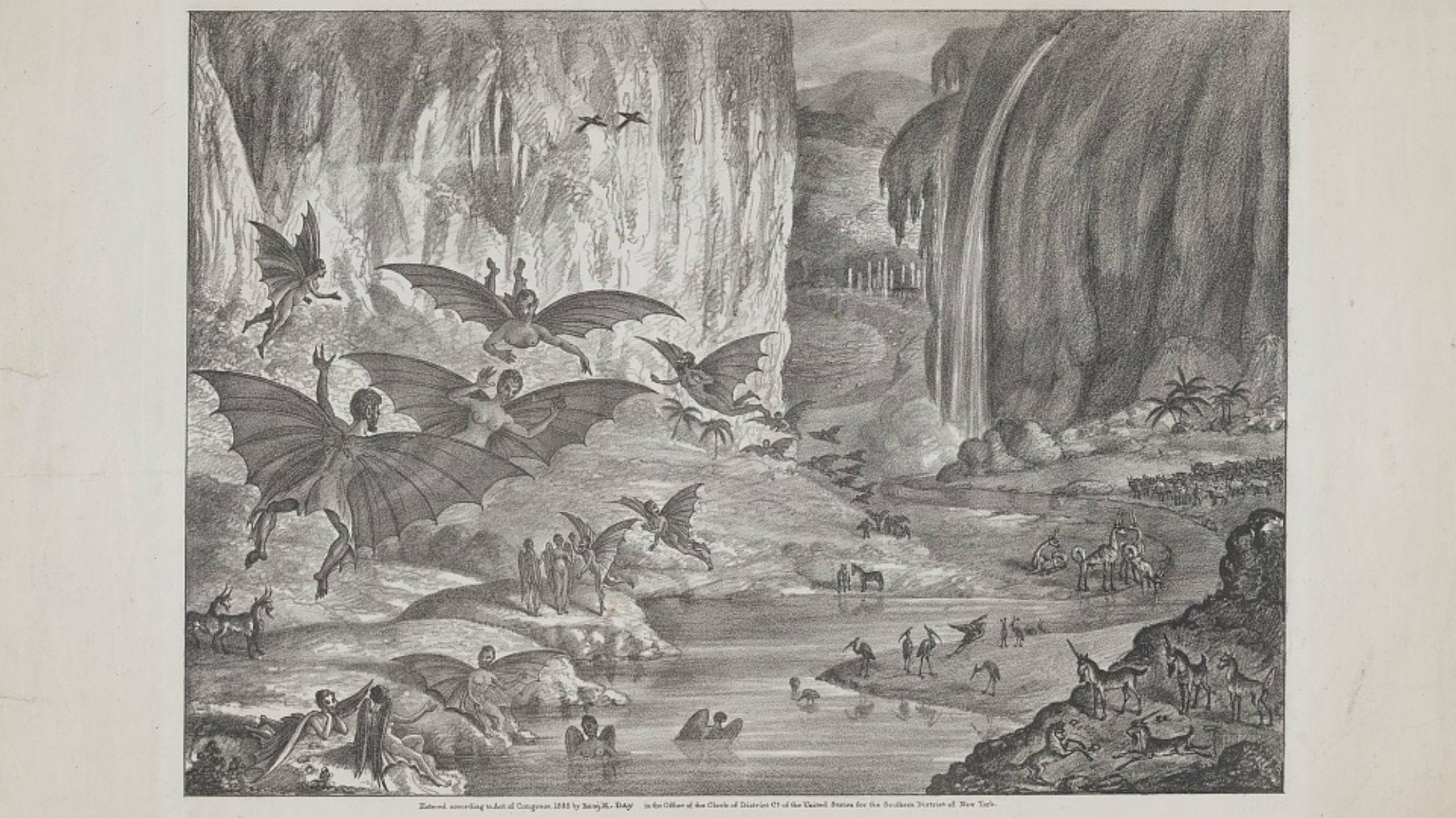

According to findings published in the Edinburgh Journal of Science, Herschel used a massive telescope to observe with stunning clarity a moonscape boasting beaches, rivers, towering cliffs of amethyst stone, rivers, plants, abandoned temples, and animals. Most incredible were a species he described as “Vespertilio-homo, or man-bat”—furry, flying men and women, each about four feet high.

The story went viral—well, 19th century viral—across the US and Europe. One Italian newspaper even commissioned lithographs to illustrate this fantastic new world. Which, obviously, did not exist.

There really was an English astronomer named John Herschel who really was studying in South Africa, who didn’t find out his name was borrowed for a scam until the story circled the globe. The rest of the tale, which came to be known as the Great Moon Hoax, is one of the earliest known examples of “fake news”—and how those who deal in falsehood respond when their account is called out.

* * *

The Sun ran the story over six days in late August. By month’s end, most New York papers reprinted the story. Within two weeks it had spread to papers up and down the eastern seaboard and as far west as Cincinnati, according to a lengthy account in the Museum of Hoaxes website. Within a month, it was in Europe. People wrote plays and painted pictures of this new moon world. The public couldn’t get enough of it.

Readers had more information coming at them than ever before. The rise of the steam-powered press and urbanization made it possible for papers like the Sun to sell tens of thousands of copies for only a penny each. The Sun was also the first newspaper to sell copies via newsboys, who shouted headlines directly at passersby—an early version of the push notification.

Publications with the most attention-grabbing headlines were rewarded with readers, who did not punish outlets that failed to meet exacting levels of accuracy.

“Readers did not yet have fixed expectations about what news was as a commodity or assumptions that it needed to be reported objectively,” wrote Mario Castagnaro, an English instructor at Carnegie Mellon University, in his 2009 doctoral dissertation on the hoax. “The early 19th century was a culture of curiosity, one in which readers did not have clear-cut expectations about truth and fiction, and the two usually blended together on newspaper pages.”

* * *

Skeptics, especially rival editors questioning how they missed the story, raised doubts almost immediately. The Sun’s response to challenges may sound familiar to anyone paying attention to the news over the past few months.

First, the paper belittled and disparaged its critics:

“Consummate ignorance is always incredulous to the higher order of scientific discoveries, because it cannot possibly comprehend them.”

Then it produced a list of eleven quotes from scientists claiming to back up the story—some taken out of context, others possibly total fabrications—and denied the existence of outlets challenging its claims.

“These are but a handful of the innumerable certificates of credence and of complimentary testimonials with which the universal press of the country is loading our tables. Indeed we find very few of the public papers express any other opinion.”

When pressed to answer reports debunking the story, the Sun declined to take responsibility. It would be at least several weeks before the Edinburgh Journal of Science could receive and reply to transatlantic requests for confirmation, the paper noted. (The journal had in fact folded two years earlier; no such confirmation would ever arrive.) In the meantime, they were just passing along what they’d heard, and had no more power to verify it than anyone else.

“Certain correspondents have been urging us to come out and confess the whole to be a hoax; but this we can by no means do, until we have the testimony of the English or Scotch papers to corroborate such a declaration.”

* * *

News that it was a hoax eventually spread, though not as speedily as the lie itself.

The writer, Richard Adams Locke, later claimed the piece was satire, not intentional deception, and that he was trying to parody the over-the-top writings of a popular sci-fi author.

The story became a meme. “Moon hoaxy” became shorthand for deception. There was merchandise.

Spare a thought for John Herschel. His contributions to astronomy were overshadowed by those of his famous father William, discoverer of the planet Uranus, and by a hoax in which he was unwittingly caught. He was hounded about it for years—“I have been pestered from all quarters with that ridiculous hoax about the Moon—in English French Italian & German!” he complained in a letter—but never spoke publicly about it.

In May 2001, his descendants found an unpublished 1836 letter to the literary magazine Athenaeum. In it he wrote:

“[I]t appears to me high time to disclaim all knowledge of or participation in the incoherent ravings under the name of discoveries which have been attributed to me. . . . I consider the precedent a bad one that the absurdity of a story should ensure its freedom from contradiction when universally repeated in so many quarters and in such a variety of forms. Dr. [Samuel] Johnson indeed used to say that there was nothing, however absurd or impossible, which if seriously told a man every morning at breakfast for 365 days, he would not end in believing—and it was a maxim of Napoleon that the most effective figure in Rhetoric is Repetition.”