Today we’re worried about smart TVs, but in the 1980s Russian spies were hacking typewriters

Ever since WikiLeaks released nearly 9,000 documents and files last week, allegedly from an internal CIA knowledge base, much has been made of the various devices the agency is apparently able to hack. The most novel of those devices, which include mobile phones and routers, is the Samsung Smart TV.

Ever since WikiLeaks released nearly 9,000 documents and files last week, allegedly from an internal CIA knowledge base, much has been made of the various devices the agency is apparently able to hack. The most novel of those devices, which include mobile phones and routers, is the Samsung Smart TV.

The “Weeping Angel” project, as described in the documents, is essentially a piece of malware that can be injected into a Samsung television’s internal computer. Once loaded, the software can turn the TV into an always-on listening device, using the built-in microphone meant for TV voice commands. The malware even includes a “fake-off mode” so that the microphone can remain on when the user believes they’ve turned the television off.

And while the idea of turning our TVs against us certainly evokes dystopian fears and confirms what everyone has always suspected about the security of the “internet of things,” the novelty of the CIA’s TV-hacking approach is dwarfed by the ingenuity of pre-internet spies. Before all household appliances had tiny, exploitable computers built into them, spies had to figure out how to extract information from devices using nothing but magnets and radio frequencies.

In the early 1980s, Russian spies did just that, according to a report released by the US National Security Agency in 2012. They developed electromechanical bugs that could be implanted in typewriters and used to transmit information as it was being typed.

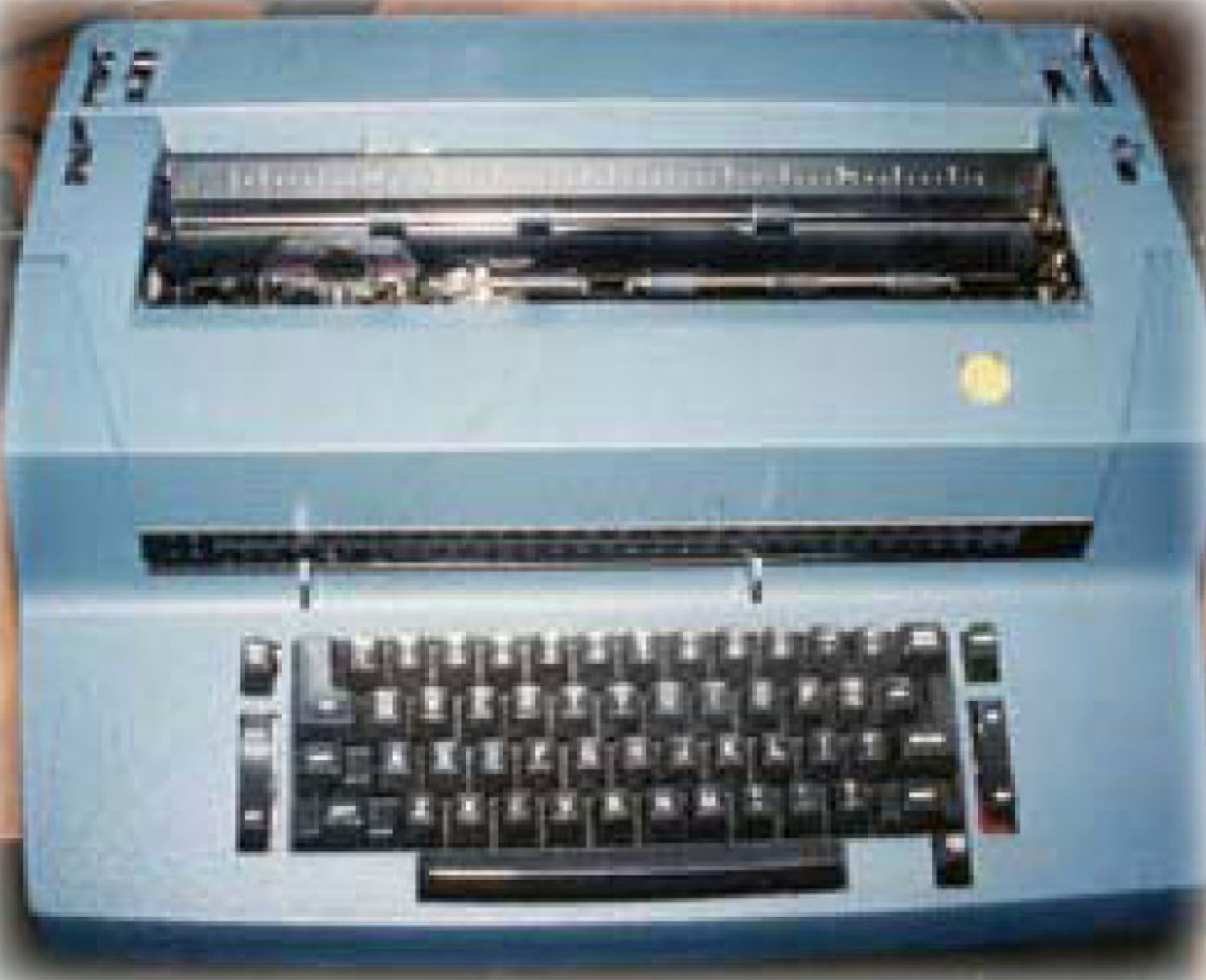

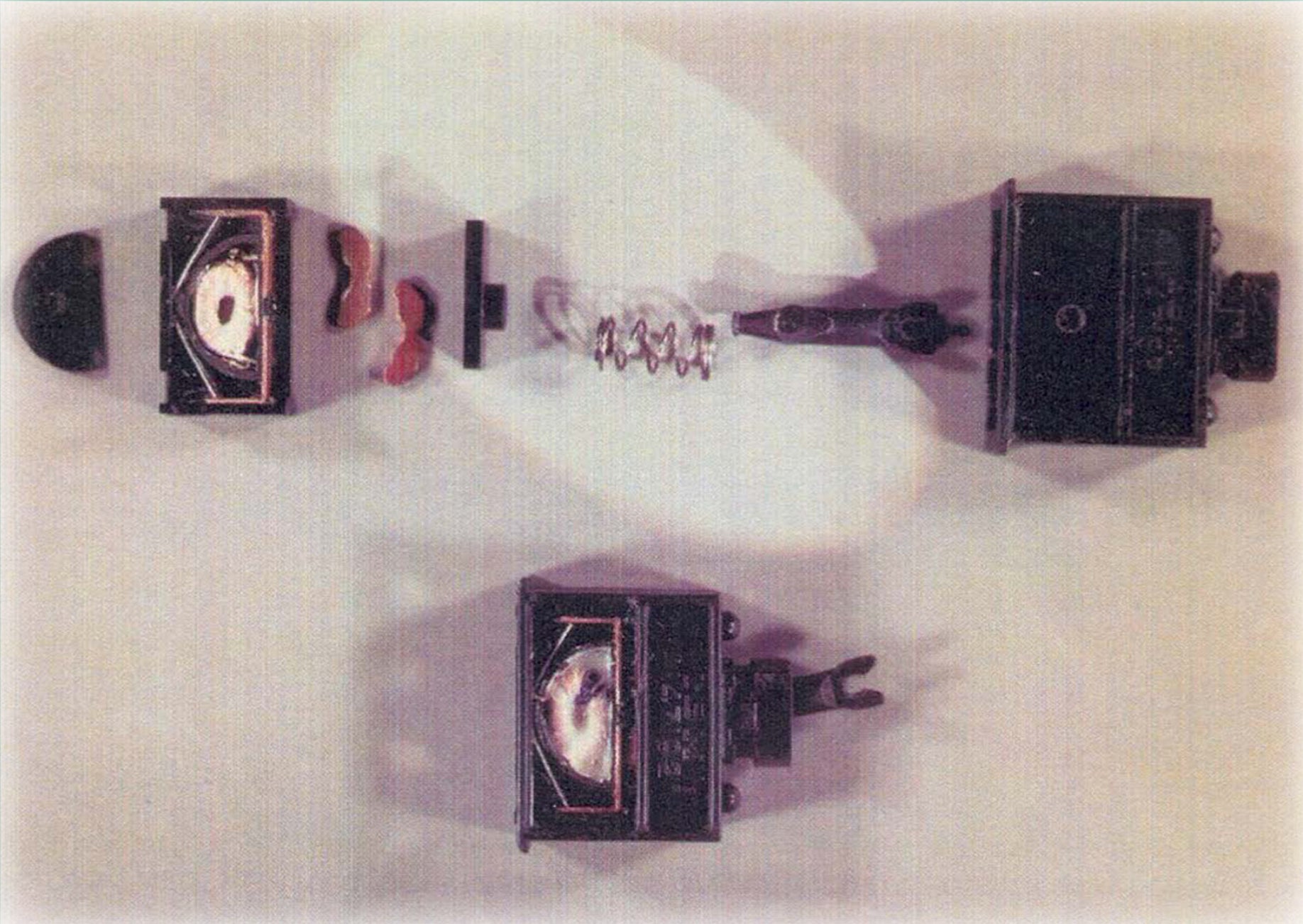

The bugs had originally been discovered in 1983 at an embassy friendly to the United States, which the report doesn’t name. Once alerted, the NSA analyzed the bugs, and found that they “represented a major Soviet technological improvement over their previous efforts.” Those first bugs weren’t found in typewriters, but it was determined that they could be used in nearly any electric device.

The implants were the first electromechanical bugs ever recovered by the agency, according to the report. Before this, the US had assumed the only listening devices its Cold War opponents used were small microphones hidden in lamps and walls.

“The development of this bug required competent personnel, time, and money,” the report says. “The very manufacture of the components required a massive and modern infrastructure serviced by many people. This combination of resources led to the assumption that other units were available.”

The US immediately determined that if the Russians had this kind of technology, the US embassy in Moscow would be a high-priority target, and the NSA launched an operation called Project Gunman. They would start by analyzing every piece of electronic equipment inside the embassy. This included not just typewriters, but also “teletype machines, printers, computers, cryptographic devices, and copiers – in short, almost anything that plugged into a wall socket.”

The goal was to replace any bugged devices with new ones without alerting the Soviets, and to bring the bugged units back to the US for analysis. But searching for the bugs ”by disassembly and visual inspection, when conducted by any but the best-trained technicians, would normally be unproductive.”

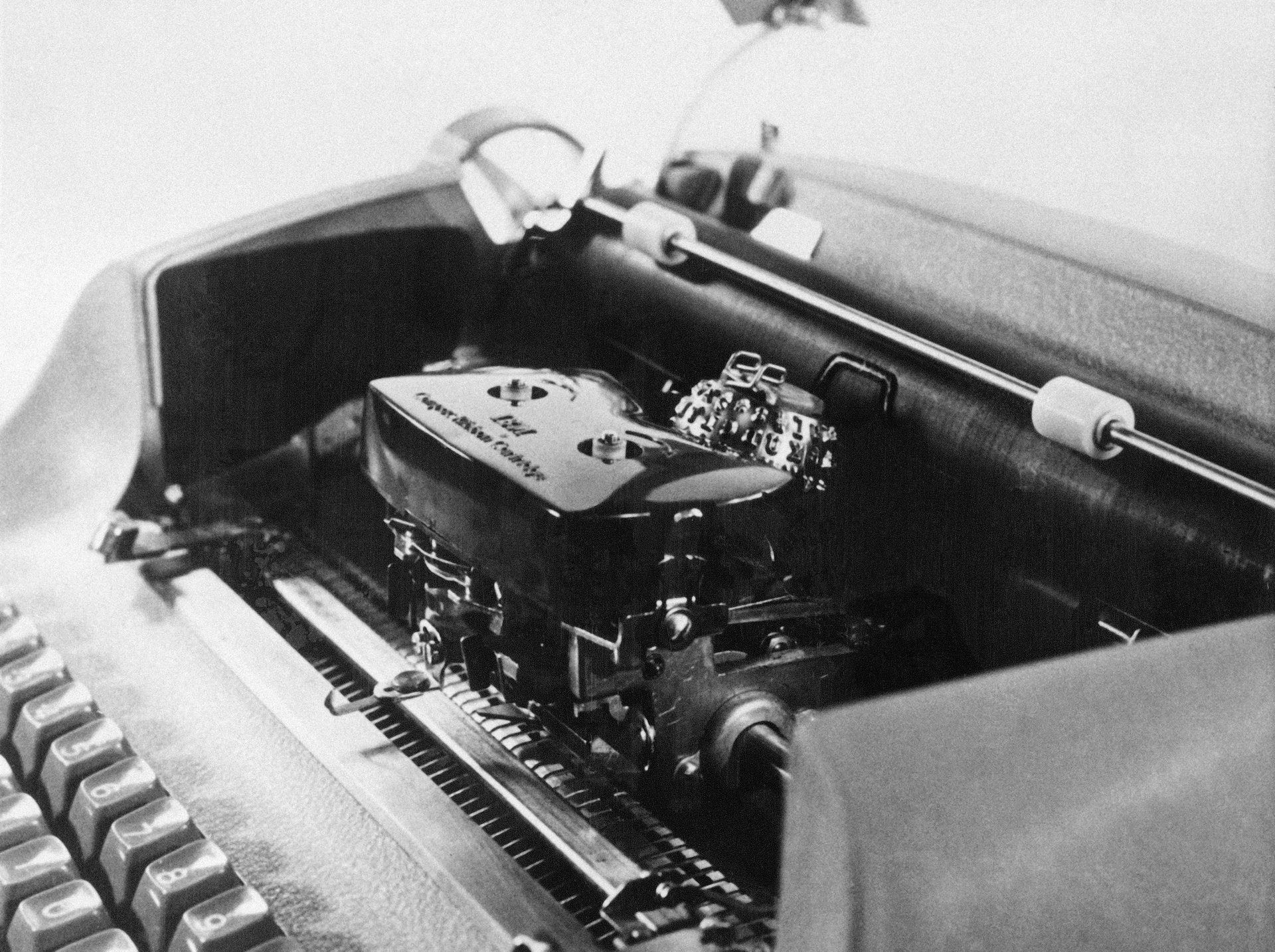

To examine equipment, they used x-rays to compare each device to a standard one. It was a lengthy process; the report notes that agents worked day and night and went through many devices without finding anything. Then, when one analyst was inspecting an IBM Selectric typewriter, he found an anomaly in one of the x-rays—an extra coil on the typewriter’s power switch. The report quotes his reaction:

“When I saw those x-rays, my response was, ‘holy fuck.’ They really were bugging our equipment. I was very excited, but no one was around to tell the news. My wife was an NSA employee, but I couldn’t even tell her because of the level of classification.”

With this discovery, the analysts knew where to focus their attention.

“Now the pace of our work really increased,” said the analyst who discovered the typewriter implant. “We had to thoroughly examine all embassy typewriters in the USSR because most likely there were more bugs. We had to educate other U.S. embassy personnel from East Bloc countries on how to search for bugs. We also began the difficult task of reverse engineering the bug to see how it worked.”

The NSA eventually discovered five unique versions of the implant, all with varying types of power sources and components. The devices used “magnetometers” to discern which keys in the typewriters were being pressed, by converting “the mechanical energy of key strokes into local magnetic disturbances,” and transmitted that information by radio. Those signals could be picked up by nearby receivers, which could then output the information being typed in realtime.

That is, of course, a much greater feat of engineering than hijacking a computer inside a smart TV and setting its microphone to stay on, and its power lights to pretend to be off. Perhaps if today’s spies had, as Kellyanne Conway recently suggested, managed to transform microwaves into video cameras, we’d have a real competition.