The repeal of Obamacare has thrown transgender Americans into a fight for their lives

Leslie McMurray makes everyone she talks to give her a hug. That’s partially because she’s a hugger, she says, but also because McMurray, a former radio personality who now advocates on behalf of HIV patients, believes that hugging itself can be a political act. During a talk she gave to Hewlett-Packard on behalf of the Dallas-based nonprofit Resource Center a few months ago, McMurray explained that when people hug a transgender person, they’re less likely to discriminate against them.

Leslie McMurray makes everyone she talks to give her a hug. That’s partially because she’s a hugger, she says, but also because McMurray, a former radio personality who now advocates on behalf of HIV patients, believes that hugging itself can be a political act. During a talk she gave to Hewlett-Packard on behalf of the Dallas-based nonprofit Resource Center a few months ago, McMurray explained that when people hug a transgender person, they’re less likely to discriminate against them.

“It’s hard to hate someone you’ve held in your arms,” says McMurray, who came out as transgender four years ago.

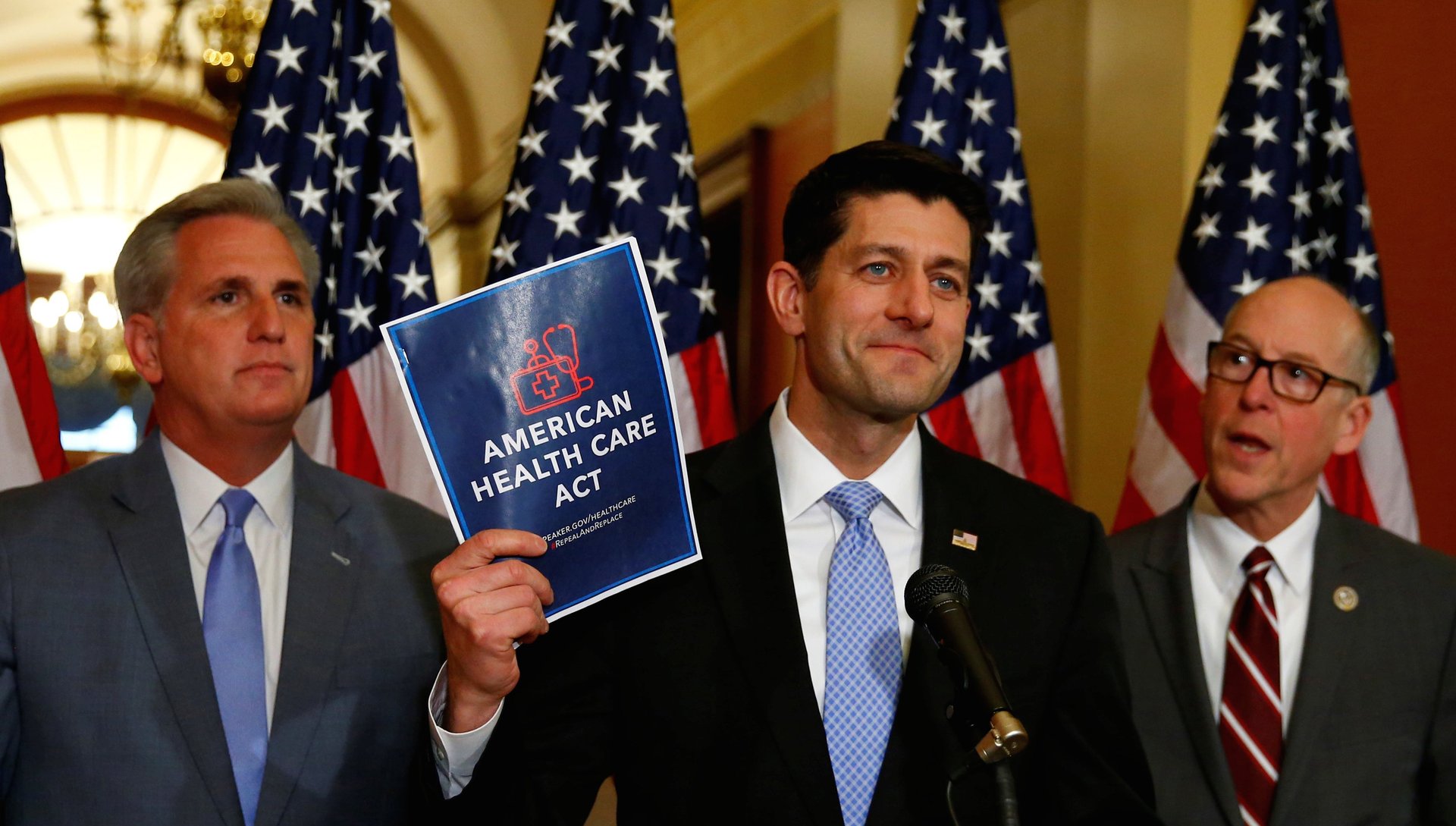

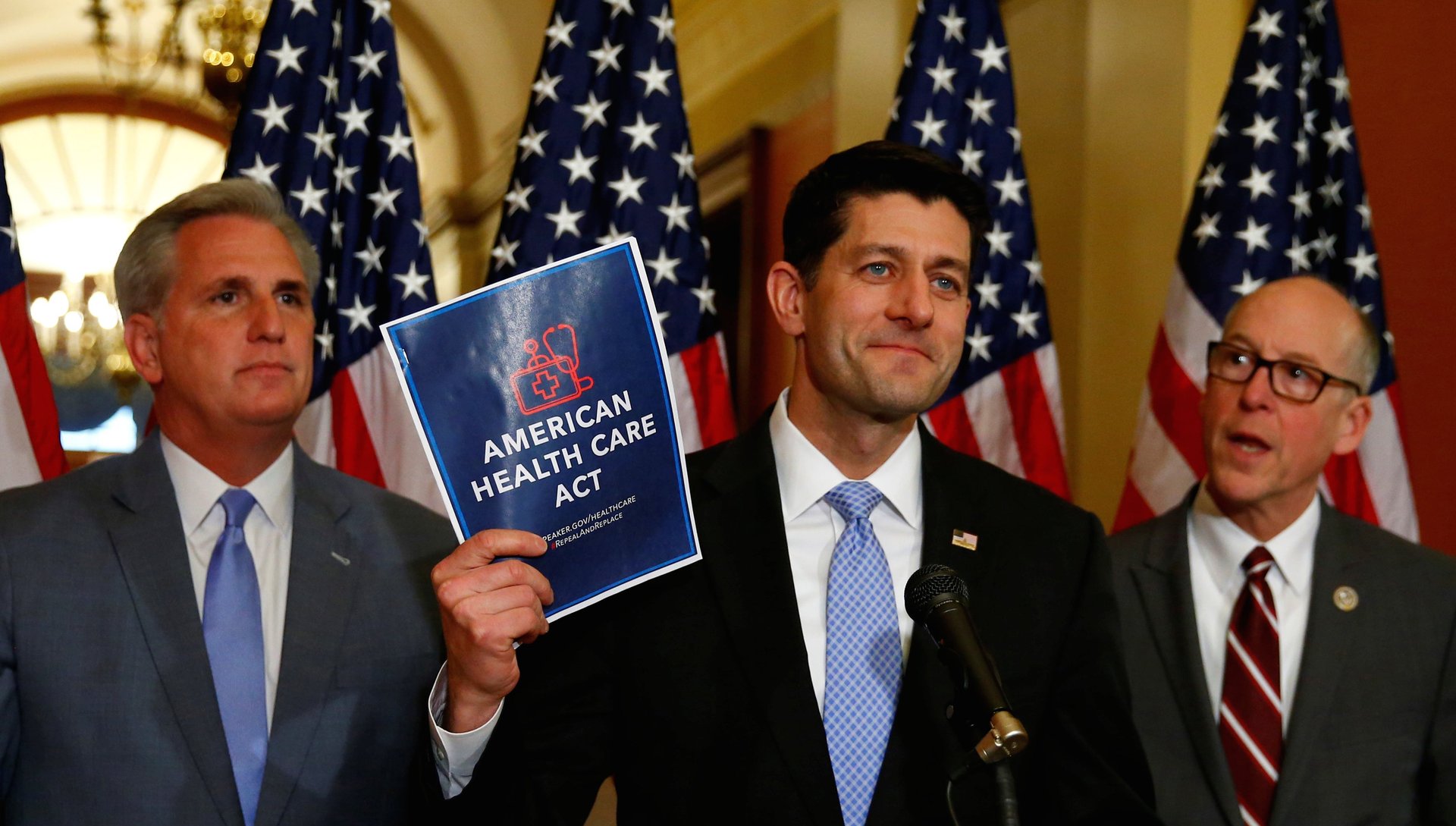

Those embraces, while small acts, have taken on a broader significance in 2017 following the election of Donald Trump to America’s highest office. Trump, who campaigned against the Affordable Care Act during his campaign, has vowed to repeal Obamacare. On March 6, House Republicans took the first step towards accomplishing that campaign promise by releasing their Affordable Care Act replacement. The bill is slated to be voted on by the House on Thursday (March 23).

While we don’t know exactly what the final bill will look like, what we do know is that a repeal of Obamacare in its current state is likely to hurt low-income Americans, the elderly, and communities of color, many of whom have only recently gotten access to health care for the first time. There’s another group, however, that will almost certainly be profoundly impacted if the Affordable Care Act is struck down: transgender people, many of whom rely on the Obama administration’s specific, trans-friendly guidelines for hormones and other transition-related care. These crucial services save lives, and they must be protected from the Trump administration at all costs.

“You’re transgender. You’re uninsurable. Have a nice day.”

Not very long ago, trans people could easily be denied health care by insurance providers because “gender dysphoria” was labeled as a “pre-existing condition.” That term, often applied to feelings of incongruence between one’s gender identity and physical appearance, replaced the outdated “gender identity disorder“ in the industry-standard setting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 2013.

The impact of the Affordable Care Act on the trans community has been profound. In 2016, the Obama administration ruled that transgender people should be granted equal access to healthcare under Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. That provision states that providers which receive federal funding must offer “health services related to gender transition” for trans patients.

“The range of transition-related services, which includes treatment for gender dysphoria, is not limited to surgical treatments, and may include, but is not limited to, services such as hormone therapy and psychotherapy, which may occur over the lifetime of the individual,” Section 1157 reads.

This is a tremendous improvement. HIV advocate McMurray paid for her transition out-of-pocket, using savings from her retirement account. She explains that prior to the Affordable Care Act, many trans people couldn’t get insurance at all, even to treat something as small as a sore throat, let alone hormones or surgery.

“When you put in an application, you got back a really nice rejection letter saying, ‘You’re transgender. You’re uninsurable. Have a nice day,’” McMurray says, adding: “That’s why transgender people are terrified. Health care is bad enough as it is right now. If the Affordable Care Act were to go away and the rules from before were to be reinstituted, transgender people would be flat insurable.”

Yet, while Section 1557 was a step forward, the health-care industry has a long way to go when it comes to providing accessible and affordable coverage for trans individuals across the US. It’s important to note that the updated regulations stop short of requiring providers to offer access to gender confirmation surgery. And many transgender people who spoke with Quartz noted that it can be difficult to get insurers to pay for other crucial necessities, including hormones like estrogen and testosterone.

Liam Hooper, a therapist and minister living in North Carolina, says that as a trans man, he’s never gotten a meaningful payment for “anything” transition related under Obamacare.

“The way they get around that is very clever,” he says. “These policies code what they approve payments for and what they don’t in such a way that they can say that they’re not necessarily noncompliant with the directive but they just don’t see medical necessity in the way we see it. For example, on my ACA policy, testosterone is coded as medically necessary only for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, which means transgender men don’t have access to it.”

This means that every month, Hooper often has to make a decision: Does he spend his money on hormones or other needs, like food and shelter?

“The needs of daily living are continually compromised,” he said. “Denial of access to resources is something we have to navigate at so many levels. If I think about it for too long, it’s really hard to swallow. It doesn’t grieve me just for myself. It grieves me for all of us. These are just basic conditions of being human.”

The problem is that so much of trans-related health care varies state by state depending on the state’s Medicaid. Individual states “legislate their own criteria for gender-affirming surgeries,” explains Ronica Mukerjee, a family nurse practitioner at Star Program in Jamaica, New York. What North Carolina is willing to cover may differ from what New York grants access to.

Currently, at least 10 states offer access to transition-related care in their Medicaid program, funding for which will slated to be cut by $880 million in the current House bill. But people living in these areas may already have trouble getting the services they need.

The ACA was still a work in progress, notes Mukerjee. “If you live in a state that says your insurance will cover trans affirming surgeries, it may still not actually work for you”—and this is under the Obama guidelines. ”You may not have anyone in your network that would be covered by your insurance plan.”

Republicans gear-up to battle bureaucracy—and data

Besides the Medicaid cuts, health and LGBT advocates fear what other aspects of Obamacare the incoming Trump plan will de-prioritize or even eliminate. Trump has thus far lost little time dismantling some of Obama’s protections for the trans community. In a deeply troubling blow to LGBT advocates, the Justice Department and Education Department rescinded Obama’s guidelines on trans students in February.

Trump’s cabinet is not much better. Tom Price, Trump’s new Department of Health and Human Services, has previously referred to the Obama administration’s landmark recommendations on equal access for trans students in public schools as “absurd.” Price, who also opposes the Affordable Care Act, called it an “overreach of power,” “a clear invasion of privacy,” and “abuse.” The message is clear: The Trump administration is unlikely to work to protect trans civil liberties under the new health-care plan.

Jason Cianciotto, vice president of policy, advocacy and communications for the HIV advocacy group Harlem United, says the elimination of Section 1557 is a real concern.

“It would ultimately kick millions of people off their health insurance,” Cianciotto says, “targeting vulnerable communities like transgender people, people of color, and those living with HIV/AIDS. It would be devastating for populations who are already underinsured under the current system and often go without health-care treatment.”

But Danni Askini, the executive director of Gender Justice League, believes that striking down Obamacare will may not be as simple as its critics might think. And it certainly won’t be as simple as an executive order.

“It took eight years to implement Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, and any repeal of the Affordable Care Act is going to take awhile,” says Askini. “Bureaucracy—especially within the health insurance industry—moves incredibly slowly. You’re talking about hundreds of companies across the country, a federal government that is serving 327 million people, and some things will not happen overnight.”

Although organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union have already vowed to fight Trump should his administration chip away at trans health care, one crucial factor is working in the community’s favor: Transition-related services are extraordinarily cheap.

Studies have shown that insuring trans individuals comes at little expense to taxpayers. In 2010, the New York State Department of Health estimated that covering gender confirmation surgery through Medicaid would add just $1.7 million to the state’s current budget, which at the time totaled $52 billion. That’s just a .003% increase. When San Francisco began offering trans-inclusive health care to city employees in 2001, the cost to taxpayers was just $386,417 over a period of five years.

In fact, because trans people were so cheap to insure, San Francisco was able to discontinue the small $1.70 surcharge for those on the City Plan, incurring no additional cost to other policy holders.

“It’s not very expensive because there aren’t very many of us,” McMurray explains, citing recent statistics showing that there are just 1.4 million trans people living in the US. “It’s not like someone with diabetes, who costs $11,000 a year to treat every single year. If you treat a transgender person with surgery, that’s it. I’ve had surgery once, and I’m very happy with it. I’m not going to have it again.”

And there’s a strong case to be made that trans-inclusive health care is actually much less costly than the alternative—both in terms of the overall price tag and the impact on the community’s livelihood.

Statistics from American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and UCLA’s The Williams Institute show that 41% of all transgender people will attempt suicide at some point in their lives. Many will do so multiple times. According to the Centers for Disease Control, each of these attempts averages $7,234 in total hospital costs. In 2011, New York estimated that additional mental health services would cost an average of $28,451 to its state Medicaid program—and that’s per patient, per year.

When transgender people receive transition-related care, though, they are less likely to experience suicidal ideation. A 1997 study from Clinical Endocrinology showed that patients who receive hormones and trans-affirming surgery had an extremely low rate of attempted suicides—as small at .8%.

These individuals are also less likely to have alcohol or substance abuse issues, meaning they won’t need to charge rehab to their insurance. It’s a win-win.

Taking the fight to the states

Given the myriad benefits of insuring trans people, many advocates are pushing states and private companies to ensure that transgender individuals will remain covered should the Trump administration target the Affordable Care Act.

Marisa Richmond, a lobbyist with the Tennessee Transgender Political Coalition, is in the process of helping the city of Nashville provide insurance to local employees, which would cover more than 600,000 metro-area residents. Richmond is also developing a list of community resources with the Tennessee Department of Health so that trans people know what options are will remain available to them, no matter what. Because the Volunteer State does not provide gender confirmation surgery through its Medicaid program, these resources will unfortunately remain few and far between for now.

But Richmond’s hope is that these smaller victories will have a domino effect in states that have yet to catch up to recent advances in policy.

“We’re hoping that once we can get one city to include transgender people—40 cities nationally have done it—other communities will follow suit,” Richmond says. “We’re also hoping that private employers will continue to advance options for trans individuals.” Currently, companies like Aetna, United, and Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield all claim some form of coverage for trans health care, although these benefits vary by state.

The problem remains, though, that many trans people won’t have access to private plans due to high rates of underemployment in the trans community. Transgender people are twice as likely as the average worker to be unemployed and more than three times as likely to have a household income that’s less than $10,000, according to 2015 statistics from the Movement Advancement Project and the Center for American Progress. Those high rates of poverty increase for people of color, especially transgender women.

These are the exact populations that will be most gravely impacted by the repeal of the Affordable Care Act—and a less inclusive replacement written by the GOP. For many in the LGBT community, this fight is a matter of life or death.

But despite widespread and justifiable panic about the future of health care, Askini has a message: The sky is not falling.

“The world is not ending,” she says. “That’s not true. We’ve made immense progress in the last 10 years both in states and at the federal level advancing the argument for covering transition related health insurance. Public awareness and education is increasing. Nothing about a hostile administration can take away the fact that cultural consciousness is moving forward. There’s no way to undo that.”