Zebra companies offer an alternative to the unicorn fantasy

A year ago we wrote “Sex & Startups.” The premise was this: The current technology and venture capital structure is broken. It rewards quantity over quality, consumption over creation, quick exits over sustainable growth, and shareholder profit over shared prosperity. It chases after “unicorn” companies bent on “disruption” rather than supporting businesses that repair, cultivate, and connect. After publishing the essay, we heard from hundreds of founders, investors, and advocates who agreed: “We cannot win at this game.”

A year ago we wrote “Sex & Startups.” The premise was this: The current technology and venture capital structure is broken. It rewards quantity over quality, consumption over creation, quick exits over sustainable growth, and shareholder profit over shared prosperity. It chases after “unicorn” companies bent on “disruption” rather than supporting businesses that repair, cultivate, and connect. After publishing the essay, we heard from hundreds of founders, investors, and advocates who agreed: “We cannot win at this game.”

This is an urgent problem. For in this game, far more than money is at stake. When VC firms prize time on site over truth, a lucky few may profit, but civil society suffers. When shareholder return trumps collective well-being, democracy itself is threatened. The reality is that business models breed behavior, and at scale, that behavior can lead to far-reaching, sometimes destructive outcomes.

Facebook — the ultimate unicorn — was weaponized to spread fake news during the presidential election. Uber has come under fire for supporting dubious political agendas, tolerating a toxic workplace culture, manipulating employee wages, and circumnavigating regulations. Medium has backpedaled, having realized that while clickbait content may produce the ad-revenue hockey stick investors want to see, it undermines the founders’ original mission to create a publishing model that enlightens, informs, and rewards quality over quantity.

Many well-reasoned think pieces have been written about the gaping chasm between the world we need and the world that exists. Today, we want to provide the seeds of a solution — and to encourage founders, investors, foundations, corporations, and their allies to organize around it.

A company’s business model is the first domino in a long chain of consequences. In short: “The business model is the message.” From that business model flows company culture and beliefs, strategies for success, end-user experiences, and, ultimately, the very shape of society.

We believe that developing alternative business models to the startup status quo has become a central moral challenge of our time. These alternative models will balance profit and purpose, champion democracy, and put a premium on sharing power and resources. Companies that create a more just and responsible society will hear, help, and heal the customers and communities they serve.

Think of our most valuable institutions — journalism, education, healthcare, government, the “third sector” of nonprofits and social enterprises — as houses upon which democracy rests. Unicorn companies are rewarded for disrupting these, for razing them to the ground.

Instead, we ought to support companies that provide extreme home makeovers. We can’t assume these companies will be created by accident. We must intentionally build the infrastructure to nurture them.

Enter the zebra

This new movement demands a new symbol, so we’re claiming an animal of our own: the zebra.

Why zebras?

- To state the obvious: unlike unicorns, zebras are real.

- Zebra companies are both black and white: they are profitable and improve society. They won’t sacrifice one for the other.

- Zebras are also mutualistic: by banding together in groups, they protect and preserve one another. Their individual input results in stronger collective output.

- Zebra companies are built with peerless stamina and capital efficiency, as long as conditions allow them to survive.

The capital system is failing society in part because it is failing zebra companies: profitable businesses that solve real, meaningful problems and in the process repair existing social systems.

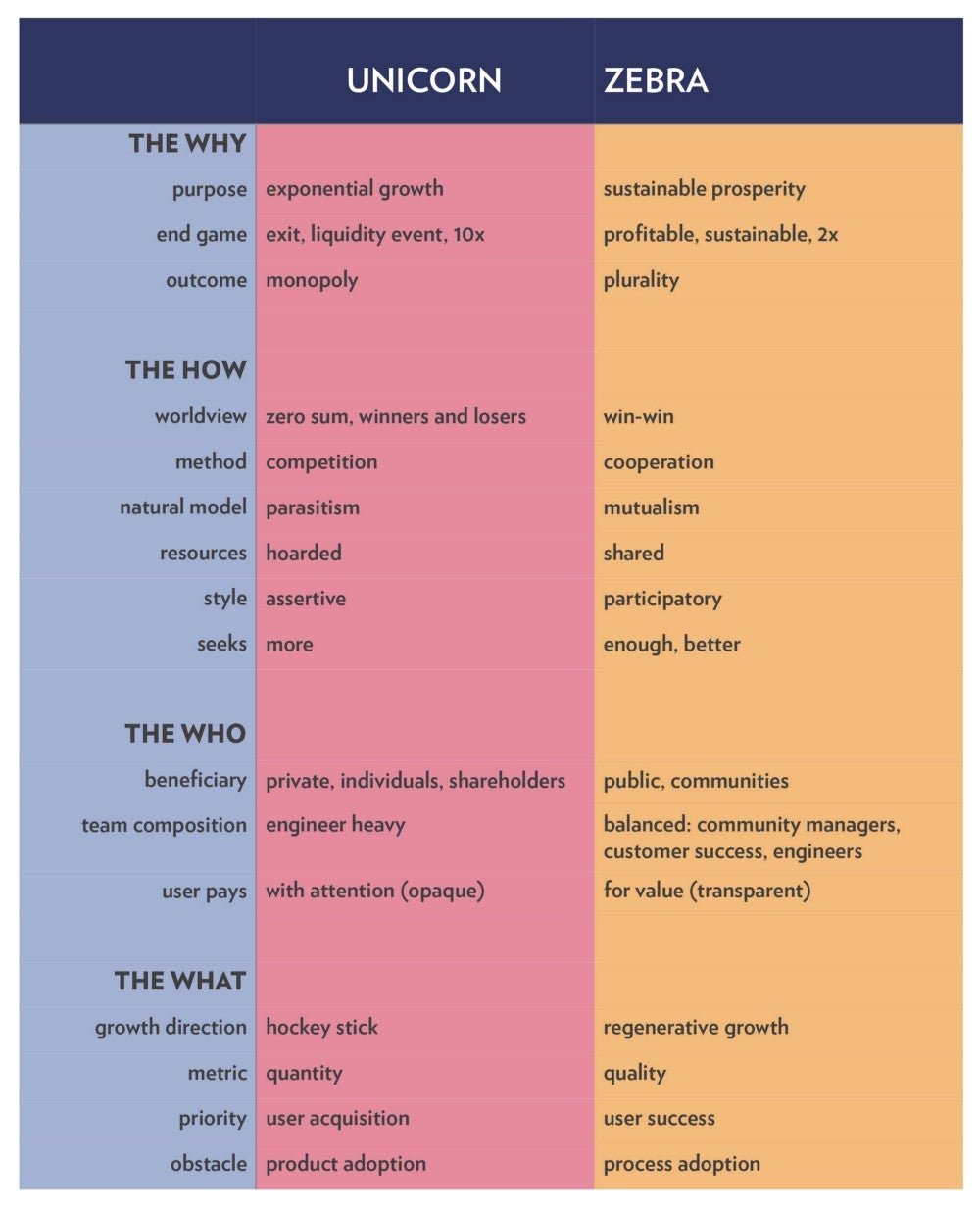

Drawing from the work of many thinkers, we’ve developed a portrait of what a zebra company is, does, and stands for. This chart outlines how a zebra company compares with its mythical cousin, the unicorn.

Why is it so hard to build zebra companies?

In the last year we’ve spoken to countless founders, investors, foundations, and thought leaders who believe zebra companies are crucial to our society’s success. Yet zebras struggle for survival because they lack the environment to encourage their birth, let alone to support them through maturity. “I wonder how many change-makers are stuck under the demands of unicorn investors,” said TJ Abood of Access Ventures, who added that he worried about “the opportunity cost to society” under this model.

From our conversations with stakeholders, we distilled the most common challenges facing zebra companies:

1. The problem isn’t product, it’s process. Tech isn’t a silver bullet. Building more won’t solve the biggest challenges we face today. An app won’t address the homelessness crisis in San Francisco or unite bitterly divided partisan politicians. The obstacle is that we are not investing in the process and time it takes to help institutions adopt, deploy, and measure the success of innovation, apps or otherwise.

2. Zebra companies are often started by women and other underrepresented founders. Three percent of venture funding goes to women and less than one percent to people of color. Although women start 30 percent of businesses, they receive only 5 percent of small-business loans and 3 percent of venture capital. Yet when surveyed, women — who perform better overall than founding teams composed exclusively of men — say they are in it for the long haul: to build profitable, sustainable companies.

3. You can’t be it if you can’t see it. Look hard outside of Silicon Valley and you’ll find promising zebra companies. But existing and aspiring business owners haven’t seen enough proof that they’ll have a higher chance of becoming financially successful and socially celebrated if they follow sustainable business practices. They lack heroes to emulate, so they default to the “growth at all costs” model. Imagine if every fund allocated a small percentage for zebra experiments. The investing firm Indie.vc has bravely stepped into this space, but it shouldn’t stand alone.

4. Zebras are stuck between two outdated paradigms, nonprofit and for-profit. For young companies pursuing both profit and purpose, the existing imperfect structures (hybrid for-profit/nonprofit, Public Benefit Corps, B-Corps, L3Cs) can be prohibitively expensive. The expense comes not only in legal fees, but in the consumption of a founder’s most precious commodity: time. Months are lost searching for aligned, strategic investors who are both familiar and comfortable with alternative models. This presents a chicken-and-egg problem for foundations, philanthropists, and investors alike. They are spooked by unproven alternative models, but companies can’t prove their models work without experiments to fund them in the first place. Moreover, the current tax system doesn’t reward — or even acknowledge — anything other than for-profit (tax) or nonprofit (deduction) strategies. From the IRS’s perspective, there is nothing akin to a “50 percent financial return, 50 percent social impact” investment. This leaves many potential investors in a straitjacket.

5. Impact investing’s thesis is detrimentally narrow and risk-averse. Much of the $36 billion in impact investment funding is restricted to verticals like clean technology, microfinance, or global health. This immature market limits innovation in other sectors — like journalism and education — that could desperately use it.

“So how will investors turn a profit and mitigate risks?” you may be asking. Dividends? Equity crowdfunding? We don’t have all the answers. But we’ve seen how a company’s business model and values can negatively affect the bottom line (#deleteuber). So what if the opposite is also true? What if more-enlightened dollars invested in more-enlightened companies led to stronger returns? What if companies that stood for something were in fact more profitable? Patagonia, Warby Parker, Zingerman’s, Etsy, Mailchimp, Basecamp, and Kickstarter are a start — but the world needs so much more.

Make zebras: Join us

If you believe technology and capital must do better, if you are building a zebra company or want to help carve out a space for them to thrive: join us.

Our goal is to gather zebra founders, philanthropists, investors, thinkers, and advocates to meet in person this year for DazzleCon — a group of zebras is called a dazzle! — to learn from one another and pool resources, ideas, and best practices, to collectively advance this set of ambitions. From this gathering, we will capture and share the unique patterns that zebra founders and funders are finding, and we’ll turn a loose network into a powerful, cohesive movement.

Are you in? Go here.