America helped create the racist myth of the violent Mexican that Trump is exploiting today

With a growing middle class, a healthy export economy, and a resilient democracy, Mexico is much more than a spring break destination for the United States. And yet, US president Donald Trump has repeatedly linked his anti-immigration campaign promises with the alleged threat posed by Mexico’s “bad hombres.” In the newly-minted chief executive’s eyes, Mexico seems to be a country that can only cause the US problems. He has also met several times with families of victims of crimes committed by undocumented immigrants and used their grief to bolster his sensationalist allegations.

With a growing middle class, a healthy export economy, and a resilient democracy, Mexico is much more than a spring break destination for the United States. And yet, US president Donald Trump has repeatedly linked his anti-immigration campaign promises with the alleged threat posed by Mexico’s “bad hombres.” In the newly-minted chief executive’s eyes, Mexico seems to be a country that can only cause the US problems. He has also met several times with families of victims of crimes committed by undocumented immigrants and used their grief to bolster his sensationalist allegations.

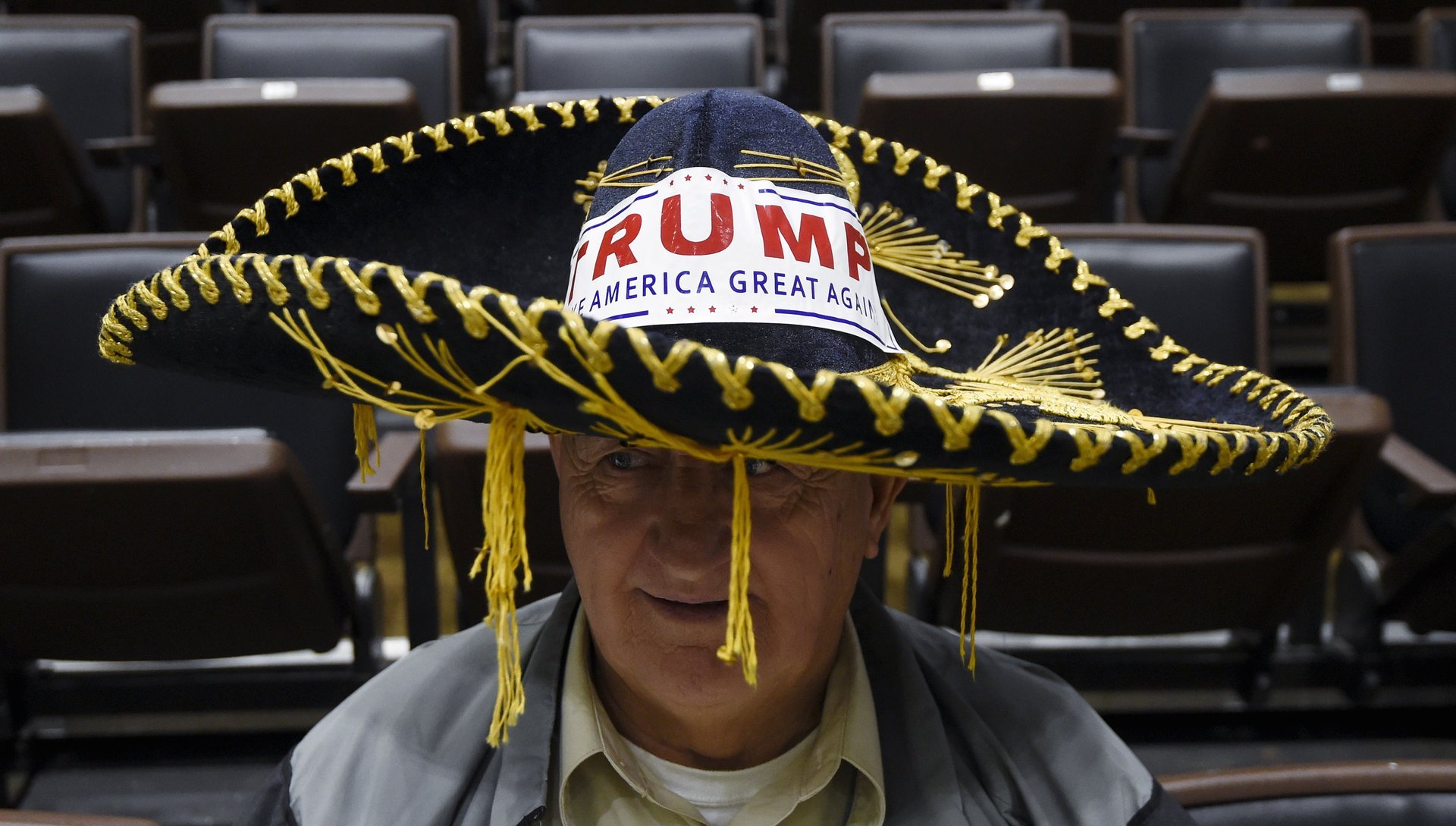

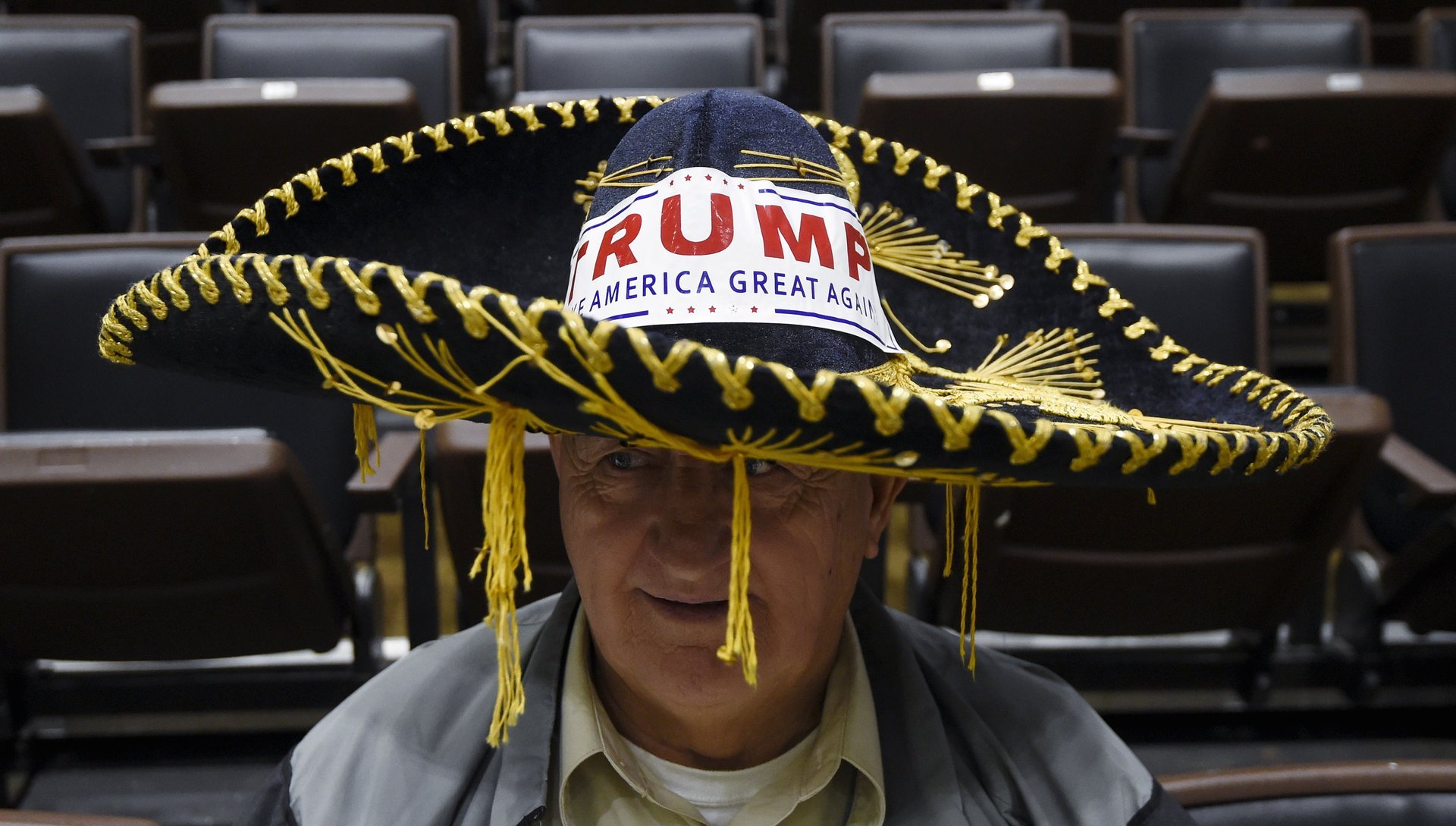

Inadvertently or not, Trump is masterfully exploiting long-held visions of Mexico as a nation defined by crime to further his political agenda. These views can be traced back to 19th-century legends about bandits robbing coach travelers between Veracruz and Mexico City, to the images of Pancho Villa or other revolutionaries in the early twentieth century, and more recently, to the threat of narcos. Ironically, while Trump is now using this reputation as a political means to an end, over the past century the US has been instrumental in the creation and perpetuation of the myth.

Mexico’s violent reputation—at least in the US—became a powerful stereotype by the mid-20th century. After a decade of revolutionary fighting cost the country around five percent of its population, a new political class emerged and changed the ways of politics in Mexico City. Hardened by civil war, this generation brought with them bodyguards who were also enforcers, gunmen that came to be known as pistoleros.

By the 1930s, some pistoleros embraced the looks and style of Hollywood gangsters: smooth suits, broad hats, and brutal methods. They acted as hired thugs for their bosses but they also got involved in their own illegal businesses, from exploiting prostitution to protecting then small-scale drug traffickers. When deputy Manlio Fabio Altamirano was shot in an elegant café in Mexico City in 1936, in front of an astonished Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, his widow described the shooter as a slick and efficient pistolero. In 1948, alarmed reports from the Mexico City embassy to Washington described rampant “political gangsterism” close to president Miguel Alemán’s inner circle. Although Mexican citizens demanded that pistoleros be punished, the US media’s narrative of Mexico as a country of illegality and danger had taken root in the minds of American readers.

This misperception was further fueled by a series of thrill-seeking US tourists, including beat poets like Jack Kerouac, Neil Cassady, and William Burroughs. Burroughs accidentally killed his wife in 1951 and was only able to escape punishment in Mexico City thanks to a lawyer whose own reputation was that of a pistolero with a law degree. Cinema eventually caught on as well, romanticizing a lawless Mexico Wild West in movies like Orson Well’s 1958 noir Touch of Evil. A recently translated noir novel about pistoleros and the underworld of espionage in Mexico City, The Mongolian Conspiracy by Rafael Bernal, is perhaps the best literary look at the myth of Mexican pistoleros and their legendary mixing of politics, business, and bad international reputation.

And yet, despite the conventional wisdom of the time, Mexico was not simple a lawless outpost in the way Hollywood lead its American viewers to believe. My research shows that during most of the 20th century murder steadily decreased across Mexico. Rates did begin to grow again, without reaching the levels of the late 1920s, by the turn of the 21st century. However this makes sense: Mexico, after all, was enjoying higher levels of education and more and more people were flocking to its cities.

Today, the recent climb in violence is connected to the growth of drug trafficking. And yet, where are the majority of these drugs headed? American neighborhoods. A seemingly insatiable US demand for psychoactive substances, coupled with the futile “war on drugs” engaged by Mexican authorities with the urging and cooperation of the US government, has one again brought violence back to the border.

This latest incarnation of the myth centers on all-powerful, hyper-violent narcos. It is true that since the mid-20th century, drug traffickers have taken full advantage of a thriving US market. Illegality made the business risky but highly profitable—and perversely, ensured that only the most violent narcos thrived. Although some narcos, like Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, enjoyed local popularity, most Mexicans viewed the growth of the industry with weary eyes. Big profits increased corruption, undermined the rule of law and, when Mexican authorities arrested big bosses, fueled internecine disputes.

Here again we have the crimes of a few being used to tar all Mexicans with the same brush. Despite Trump’s xenophobic accusations, Mexicans have paid the overwhelming price for the so-called War on Drugs. More than 100,000 of people have died and tens of thousands of disappeared since 2006. Large and small gangs have branched out of drug trafficking to include human trafficking, kidnapping, and extortion. When journalists and human rights organizations attempt to speak up, they are often met with violence.

While drug-related violence has been devastating, Trump’s use of anti-Mexican mythology is potentially even more toxic. With little evidence to back him up, Trump continues to justify the construction of his border wall by citing the threat of migrants. The reality of course, as research proves, is that immigrants commit fewer crimes than native-born people of comparable age in the US. They often come to the US fleeing violence in Mexico and Central America, and they provide essential labor in some sectors of the US economy. Yet Trump’s grasp of the facts echoes William Burroughs’s explorations of Mexican mind-altering products.

Prejudices, myths, and conspiracy theories can in their own way alter reality. Republicans in Congress are willing to fund the wall, creating an additional reason to paint Mexico as a national adversary. It is unlikely that the Mexican government will agree to pay for it, thus potentially imposing a new reason for antagonism between the two nations.

In the decades following the war of 1846 and multiple US interventions, Mexico has gradually managed to foster stable regimes and mend fences with the northern neighbors. The current tensions throw some of this progress into jeopardy, and could even lead to costly commercial and immigration disputes in the short-term.

Through it all, Trump’s characterization of Mexicans as criminals seems likely to remain a theme that he and the Republican party generally can exploit for electoral gain. Hopefully, however, Mexico-US relations will outlast and eventually transcend these negative stereotypes, depositing the legend of the violent Mexican into the same mythical past that cowboys now inhabit.