As the 20th anniversary of the handover to China nears, Hong Kong artists meditate on space, memory

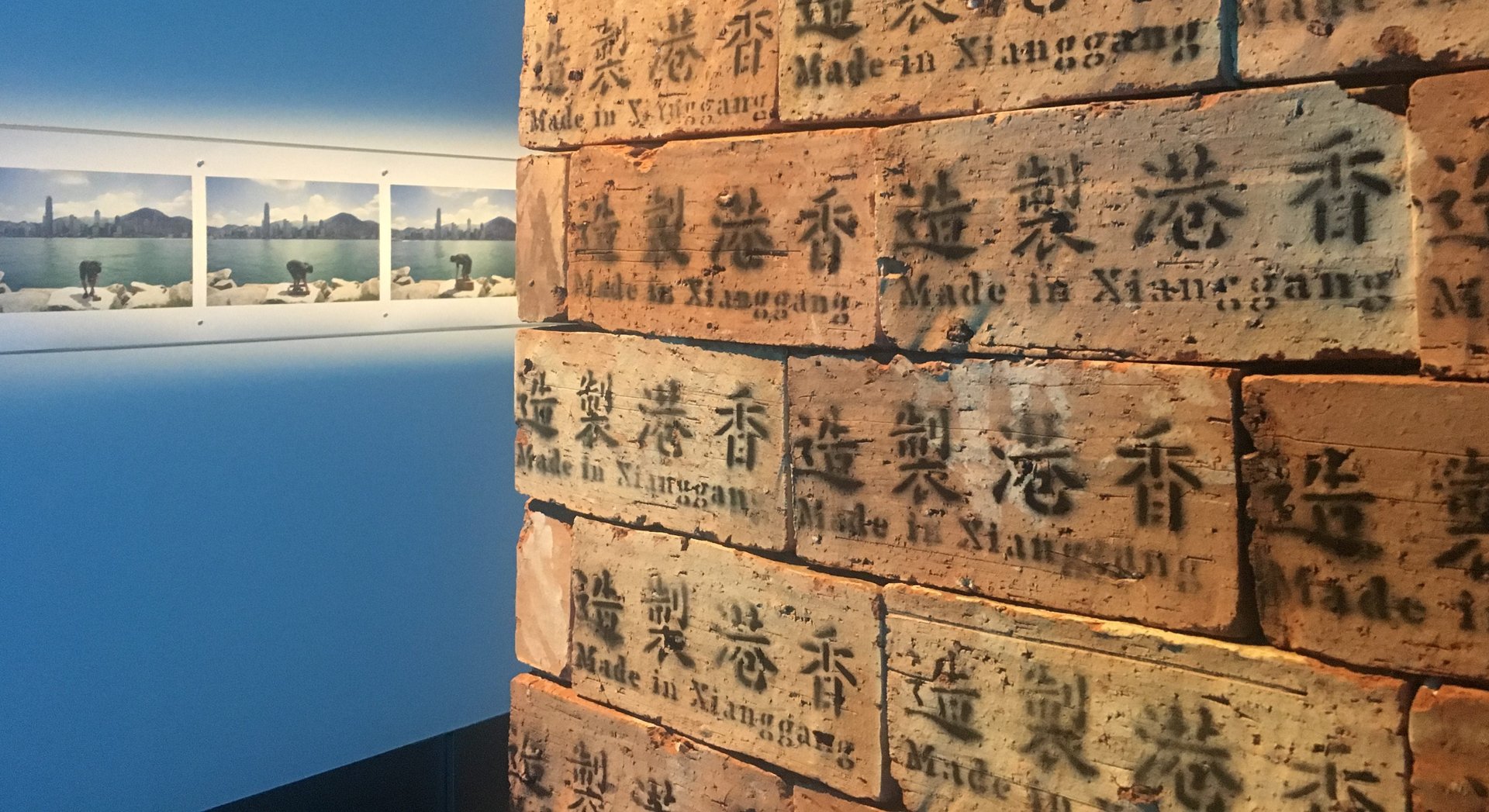

A series of photographs on a wall captures artist South Ho as he builds a wall around himself, a sparkling blue Hong Kong harbor behind him. Nearby is a tumbling tower of red bricks printed with the words “Made in Xianggang”–the Mandarin way of saying Hong Kong. Ho’s website describes the work, Defense and Resistance, created in 2011, as expressing “the confrontation between Hong Kong people and tourist from the Mainland China in recent years.”

A series of photographs on a wall captures artist South Ho as he builds a wall around himself, a sparkling blue Hong Kong harbor behind him. Nearby is a tumbling tower of red bricks printed with the words “Made in Xianggang”–the Mandarin way of saying Hong Kong. Ho’s website describes the work, Defense and Resistance, created in 2011, as expressing “the confrontation between Hong Kong people and tourist from the Mainland China in recent years.”

Another work, Rally by Cheuk Wing-lam, evokes reflections on obedience, and how orders from on high are handed down and enforced. In it, four small machines each placed on a pillar mimic the staccato Morse Code sounds played by another machine on a higher pillar. No explanation of the work is given, but the exhibition is taking place in Admiralty, which was a main site for the Occupy protests, also known as the Umbrella Movement, of 2014, and where violent clashes sometimes occurred as police tried to subdue protesters.

Both works are part of a show that opened at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center in the run-up to Art Basel, whose fifth edition in Hong Kong is taking place right before Sunday’s contentious chief executive election, in the year when the territory marks the 20th anniversary of its return to Chinese sovereignty.

Hong Kong artist Kacey Wong, whose eye-catching public art can often be seen at major political rallies in Hong Kong, including the annual January 1 anti-government protests in recent years, and who’ll be hosting a talk on his work on Friday, says the appearance of politics in the region’s art was inevitable. “Artists simply can’t help responding to the social condition,” he said. “Their works are just statements to reflect what’s going on in the society.”

It’s Not Personal

Dominique Chan, curator of Breathing Space: Contemporary Art of Hong Kong, showing the work of Ho and Cheuk along with that of other artists, says in the past Hong Kong artists focused more on intimate works expressing their personal feelings. Now, he says, the work is often likely to offer a commentary on the world. In this case, the focus of the show is on restrictions, from the spatial to the historic.

“These days, they also look around what’s happening in the city–socially, economically and politically. They embed messages in their works. That’s a very distinctive change in the shift of their artistic language,” Chan says.

The form of the work also reflects changes in Hong Kong, including the ever-lessening living space available as property prices rise, often as a result of investment from mainland China. “The fact that they tend to produce installations that are compact and can be stored easily and apply digital technology in their works is also a mirror to their living conditions,” he said.

Breathing Space is a departure from the exhibitions that Asia Society Hong Kong Center has presented in the past in March, known as Hong Kong art month. Previously, the center showcased blockbuster shows of world famous artists in March, such as Yoshitomo Nara’s Life is Only One in 2015, to capitalize on the traffic from Art Basel. But this time, the center decided to take gamble and stage a group show of emerging local artists less known to global art aficionados, its first major exhibition of Hong Kong’s contemporary art.

Creating, Curating Political Art

Art Basel, which opens to the public on March 23, after two days of VIP viewing at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, first landed here five years ago after the fair’s organizer, MCH Swiss Exhibition (Basel), acquired a majority stake in Asian Art Fairs, organizers of an earlier art fair.

Art Basel has helped seal Hong Kong’s status as one of the world’s most important art markets, alongside the city’s vibrant auction and growing gallery business. Though the fair is about sales of multi-million dollar artworks, it also aims to make art more public and accessible, and in the process has become a place to see and be seen. Last year, the fair had to stop selling public tickets before it closed because it maxed out its capacity.

Although the fair is primarily a trading ground, politics has made its way here too. Also on Friday (March 24), Hong Kong artists Chow Chun-fai, Wen Yau, and Sampson Wong, together with Cosmin Costinas, executive director of nonprofit art space Para Site, will hold a panel discussion entitled “Does political art matter?” (This author will be moderating the event.)

“Political art shown at art fairs and galleries is very different from how it appears in the street as protest art. Art fairs are a spectacle. We shouldn’t be asking how much political art is shown at an art fair. We should be asking how museums handle it. If museums cannot show political art, it’s a much bigger problem,” says Kacey Wong. “The practice of self-censorship common in China could be spread to Hong Kong soon.”

“June 31, 1997”

Artist David Clarke urges viewers to take a step back when they stand before these works and consider “where we are at the moment.” He says his own work is shaped by that and by his interest in the human condition. “And naturally that will become political, especially when we talk about freedom and aspirations,” he says.

Clarke, an art historian and a professor at the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Hong Kong, says that the opening up of China put mainland Chinese art on the world map, while the Occupy protests brought Hong Kong back into the international limelight. “[The protests] made people more sympathetic with our issues, and the visual-making [street art created during the protests] was a very big part of that. I think it helps in giving people a feeling that Hong Kong can still be a city that still has freedom and creativity, and it might change China one day,” he says.

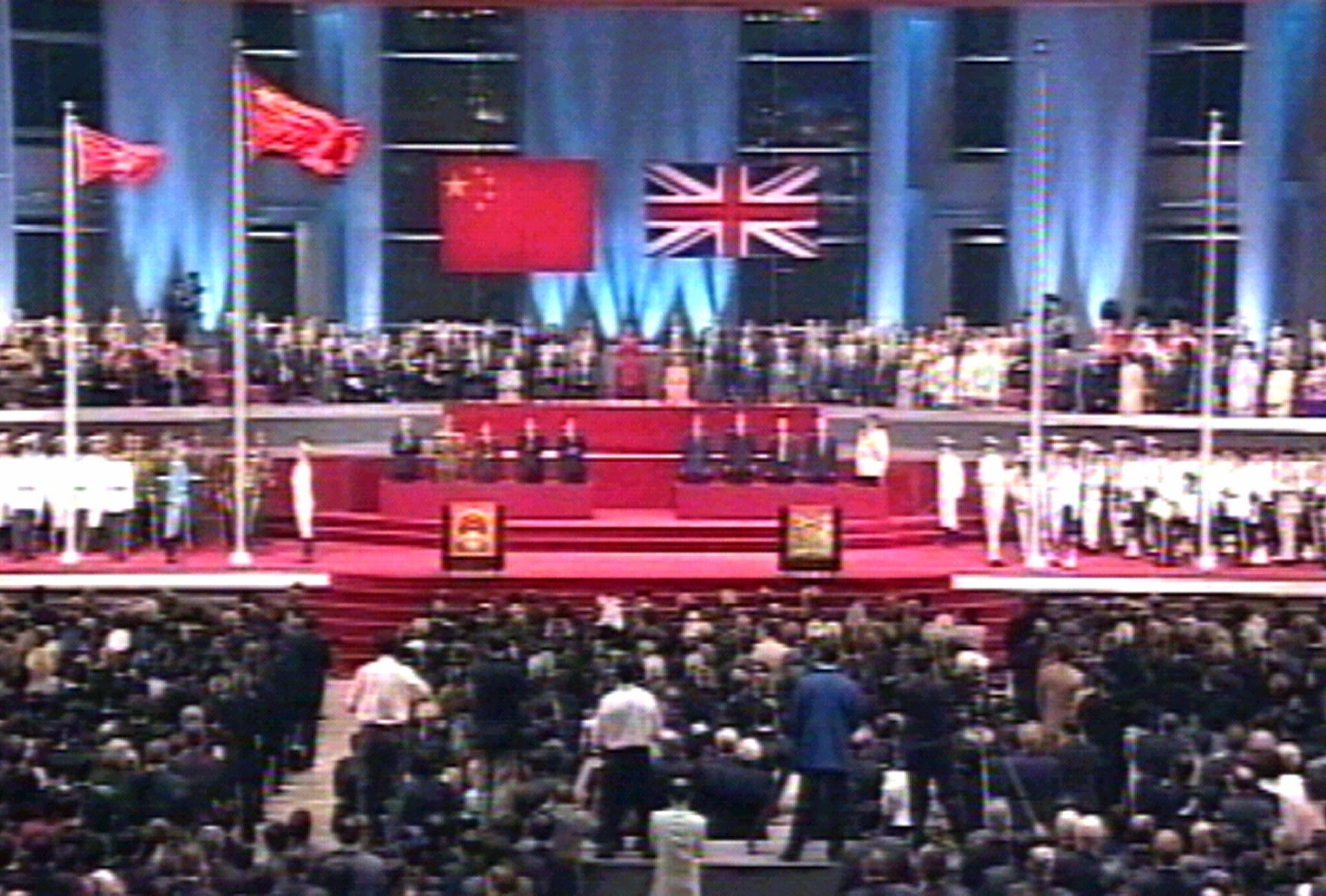

Clarke is now preparing an exhibition inspired by the history of handover, which will open around July 1, the day Hong Kong became a part of China 20 years ago. The show will feature videos of his interviews with 50 people of various ages of their memories of June 31, 1997, a day that never existed.

He says the work is inspired by the 10-second uncomfortable silence during the handover ceremony. “There was a 10-second hiatus between the British and Chinese national anthems during the ceremony,” he says.

In Clarke’s imagination, that 10 seconds is a day when Hong Kong belongs to neither Britain nor China. He says as part of his research for the piece, he asked people to recall what they did on June 31, 1997–a question that many answered by offering him recollections they appeared to believe to be of that day. He says he also came across some records that bore that date–most likely, he suspects, as a result of clerical error.

Memory and identity have been big themes in Hong Kong art, says Clarke, and besides acting as a reflection of the handover, he wants to prompt people to think again about the nature of memory.

“People think of memory as a photograph, but it’s much more creative and slippery. It is not that simple to get a sense of the past,” he says. “The work is about how people felt about the handover, and how we feel now when we look back. It is important to remember these events.”