The surprising ways neuroscience can help design smarter, more intuitive cities

We have used economics, creativity, and technology to shape the built environment—and now it’s time for science to become the final piece in this puzzle. By integrating aspects of cognitive neuroscience into the design process, we can build cities that are primed for their residents’ health and happiness.

We have used economics, creativity, and technology to shape the built environment—and now it’s time for science to become the final piece in this puzzle. By integrating aspects of cognitive neuroscience into the design process, we can build cities that are primed for their residents’ health and happiness.

The “smart city” movement started the conversation. This trend focuses on advanced technologies and geo-spatial sensors to help make the utilities and transport industries more financially efficient. For example, companies such as AppyParking, Waze, and Uber solve private automotive problems of mobility while providing valuable data to city authorities. Likewise, Space Syntax and Sidewalk Labs LINK-NYC Kiosks measure noise, pollution, and pedestrian movement.

While companies like these answer the question of what is happening within a city, they are not providing the biometric feedback to explain why it is happening and how the city is impacting its residents. If we were going to have a truly “smart” city, it would measure impact, not just action, and then use that data to improve the lives of its residents.

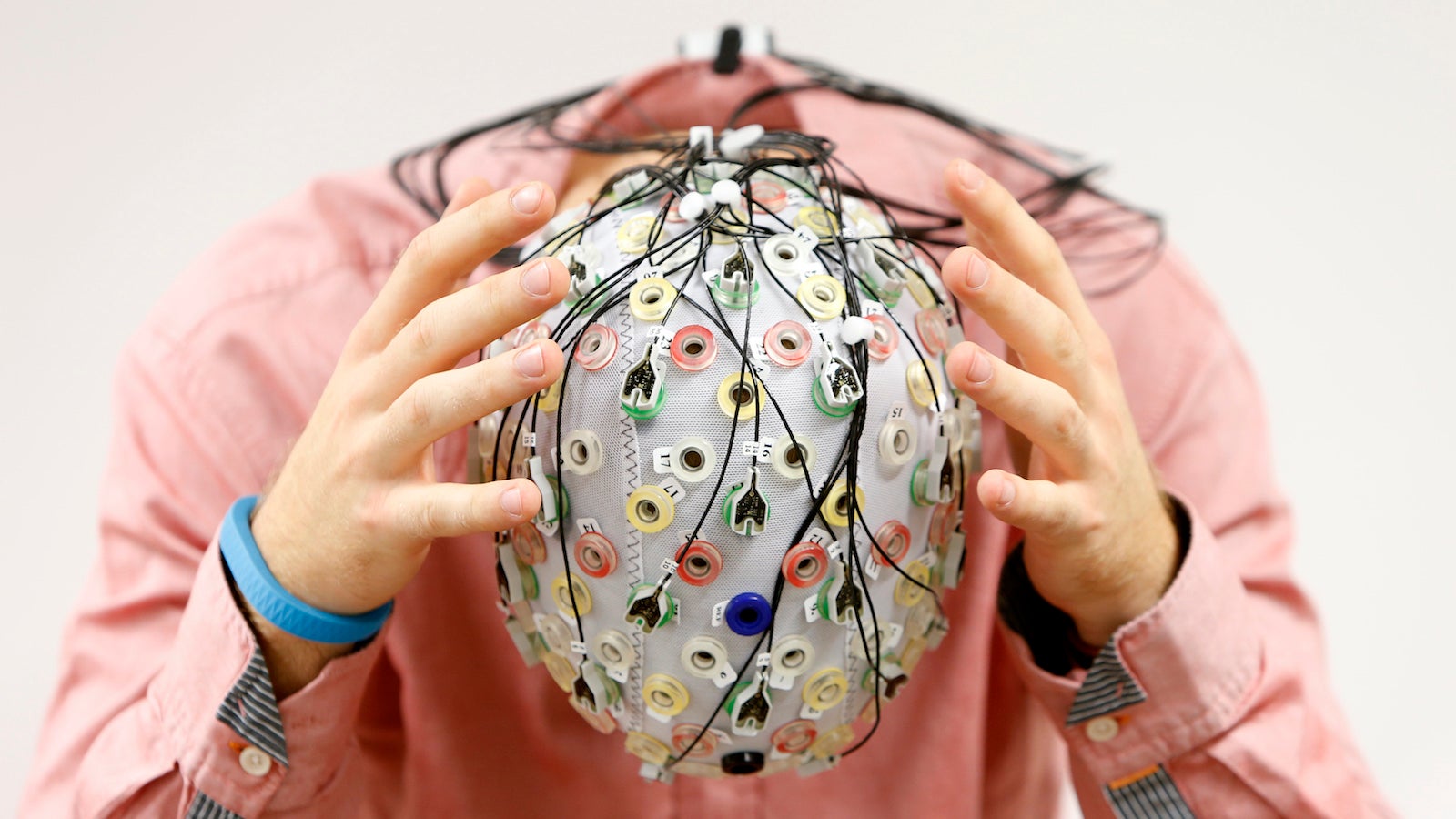

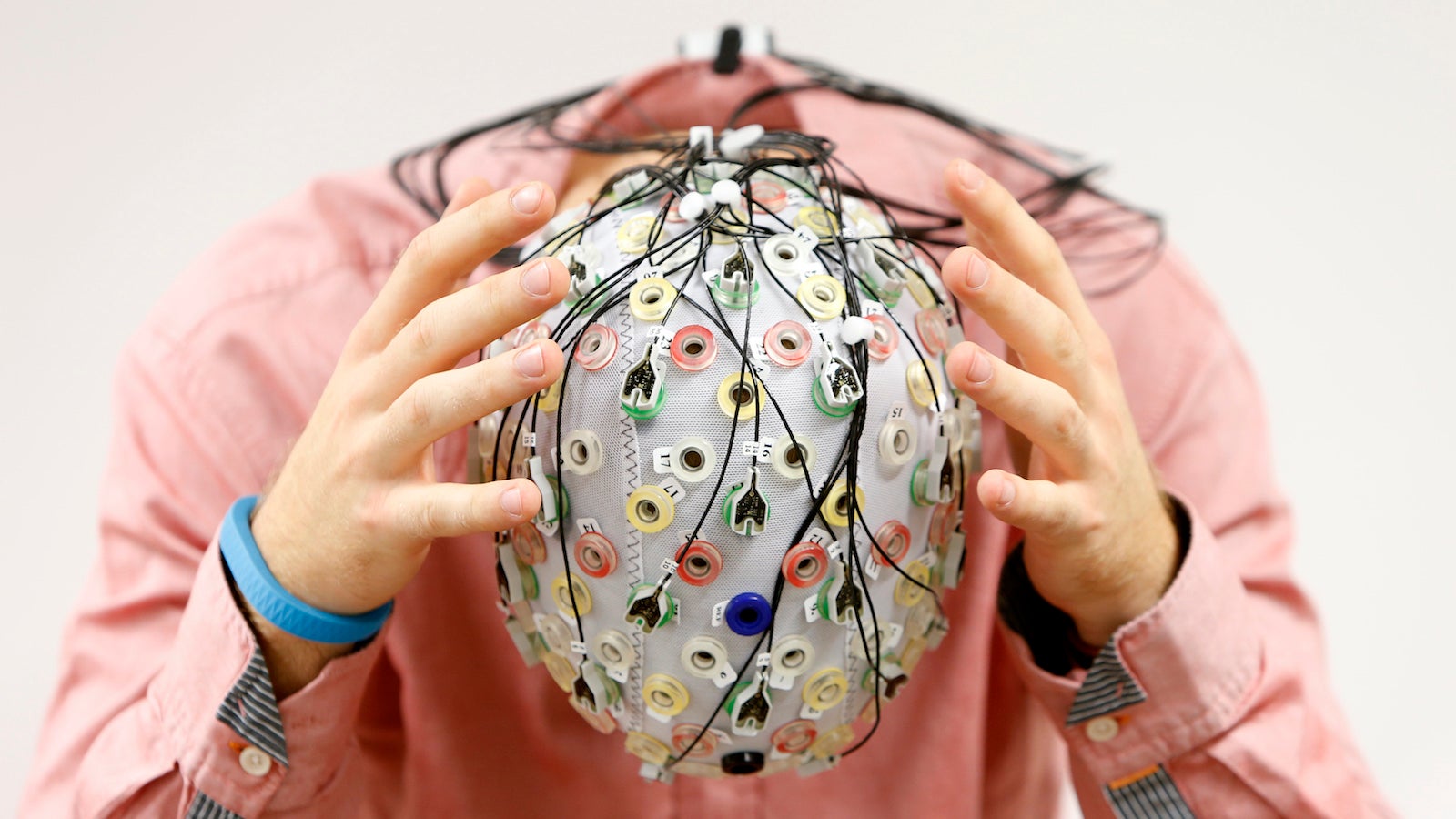

Science can add to the wealth of existing technologies to create more effective human-centric cities. “Technology has now reached the stage where we can translate decades of neuroscience and psychological research from the lab into the city,” says neuroscientist Dr. Hugo Spiers of University College London. We can now measure behavior, cognition, emotional reactions, physiological markers, and brain activity in regards to our surroundings. For example, we can track a resident’s reactions as they wander the streets using high-quality mobile electroencephalography (EEG) devices. These are helmets with small sensors attached to the scalp that allow neurophysiologists to view the electrical signals produced when brain cells send messages to each other.

Combine these kinds of technologies with state-of-the-art methods used in smart cities, and we have access to a powerful understanding of both space and the person within it. With this understanding, we can help change cities for the better, such as mitigating rising levels of stress and anxiety disorders associated with city living.

Our cities are increasing in density and sprawl with increased urbanization. Couple this with factors such as increased noise, reduced natural space, and an uncertain economic market, and our anxiety levels are rising, leading to increased levels of neurochemicals such as cortisol in our bodies. While cortisol is a necessary hormone valuable for regulating blood pressure and assisting in life-threatening situations, it can have a negative effect when experienced at a sustained level, such as disrupting people’s sleep and reducing neuronal connections.

For those who have to solve complex cognitive tasks in our daily lives, stress literally inhibits success on a biological level : The cortisol travels into the brain and binds to the receptors inside many neurons in the cytoplasm. Through a cascade of reactions, this causes neurons to admit more calcium through channels in their membrane. In the short-term, cortisol presumably helps the brain cope with a life-threatening situation. However, if neurons become over-loaded with calcium, they fire too frequently and die—they are literally excited to death.

We should encourage architects, designers, and urban planners to apply this knowledge to their design processes. Unfortunately, many of us have got caught up in the hype machine of Google-type multidisciplinary offices, which aim to create the non-office: a place where imagination, creativity, and productivity are embodied in spaces designed as boats, with slides, and over-stimulating patterns and designs. But the excitement caused on a short-term basis by playful activities is not sustainable; it drains neurochemicals such as serotonin that are required by your body throughout the day. Spikes in the release of such chemicals are met with equal troughs. Understanding the neuroscience that affects design decisions such as these can help us avoid making the same mistakes.

We should also consider cognitive neuroscience when it comes to designing new buildings. There is an opportunity for engineers to understand more about the relation of light, air, and temperature to cognition. For example, an Italian study found that patients with depression who were exposed to direct sunlight in east-facing rooms were able to leave the hospital nearly four days quicker than a control group whose rooms faced west. With the average cost of a day in the hospital over $2,000, early exits can deliver substantial savings. Such studies such support the contention that buildings should introduce natural-light sources to increase wellbeing.

And it’s not just about well-being: There is a growing economic argument for a much-needed change in how we understand the relationship between people’s wellbeing and a city’s influence on it. Sick days and office loathing alone contribute an annual private-business loss of £29 billion in the UK and $180 billion in the US each year. If we used science to make informed design and architectural decisions that increase health and happiness, we could begin filling in this chasm.

So what are the next steps to using science to design mentally healthier, more economically viable cities? The sustainability movement has already led to the development of BREEAM and LEED status for buildings. We need the biological and neurological industries to do the same for mentally healthy and conscious spaces. We need to find ways to give designers access to the information and resources that abound at the intersections of neuroscience and urban design.

And it’s starting. Conferences such as Conscious Cities bring together the disparate groups in academia and industry. More directly, the MIT SENSEable City Lab is looking at the biological science of a city by measuring a city’s sewage, aiming to find patterns relating to illnesses and their geographical areas. These insights are set to inform design and governmental policies. The Centric Lab also works with University College London in applying the advancements in neurotechnology, modeling programs, and advanced research and testing facilities to shed greater light on human experience in the built environment.

Understanding how the built environment makes its inhabitants feel allows us to pinpoint where to make innovations that enhance well-being in a city. Through deeply and meticulously studying human behavior, we are able to add another layer of data and intelligence to the design of the built environment.