That 12-year-old screaming at you while playing “Call of Duty” might actually be gaming for school

The mud-soaked and fog-blanketed World War I-inspired landscapes of Battlefield 1 can be brutal environments. Hundreds of thousands of gamers log on daily to shred airborne opponents while piloting fighter planes like the Red Baron and gallop across the desert like Lawrence of Arabia. But the vast majority likely won’t analyze whether their aerial acrobatics match those of Baron von Richthofen—the ace of aces among WWI’s fighter pilots—or if their desert warfare tactics rival those of T. E. Lawrence—the British strategist who aided the Arabic fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire.

The mud-soaked and fog-blanketed World War I-inspired landscapes of Battlefield 1 can be brutal environments. Hundreds of thousands of gamers log on daily to shred airborne opponents while piloting fighter planes like the Red Baron and gallop across the desert like Lawrence of Arabia. But the vast majority likely won’t analyze whether their aerial acrobatics match those of Baron von Richthofen—the ace of aces among WWI’s fighter pilots—or if their desert warfare tactics rival those of T. E. Lawrence—the British strategist who aided the Arabic fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire.

I am a member of the minority.

My first foray into gaming came in middle school, and my favorites were based in history: Medal of Honor: Allied Assault; Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings; and the seminal Battlefield title, Battlefield 1942 (Battlefield 1 was released in Oct. 2016). Early on, I wondered how historically accurate they actually were, and as I got older, I grew more curious about how successfully history could be taught through those games.

Some university professors, including Matthew Gabriele of Virginia Tech and Pieter Keulemans of Princeton, have found mainstream games to be useful tools for teaching some elements of their subjects and for connecting with students. “Games are a completely new medium, and I think it makes me, as a scholar, rethink the other media,” says Keulemans, an East Asian studies professor who has used the Dynasty Warriors franchise and other games to help teach the historical narrative of China’s Three Kingdoms, a conflict-ridden and bloody era of Chinese history.

Middle- and high-school teachers use video games as well. “As a teacher, you’re trying to find new ways to connect with kids,” says Scott Jackson, who has used Mission US—a game developed specifically for the classroom—to teach US history to his 11th graders at Brooklyn International High School.

Of course, video games, particularly those designed primarily for mainstream entertainment, will not replace textbooks, historical documents, and other traditional tactics. “If video games were the only way you accessed history in a classroom, I think that would be hugely problematic,” Keulemans says. “I just see it as one more tool.”

There’s not much research available to prove whether or not game-based learning even works, according to a 2012 paper that University of Connecticut researchers published in the Review of Educational Research. The studies that have been done to date lack a cohesive theme or line of inquiry from which to draw any inferences about video games’ ability to aid students, the paper says.

The paper does cite one interesting 2010 study in which 74 undergraduates were split into two groups: one listened to a history presentation and the other played an American Revolution-version of Civilization IV. Although the study found no significant difference between the knowledge gained by either group, it did suggest that those who played the game remembered the information longer.

History, however, is far more convoluted than the largely linear narratives of many popular games. Each game has a story it wants to tell, and it tells that story by getting the player to complete given objectives. An example storyline from Age of Empires II: 1) Convince a tribe to join Genghis Kahn. 2) Kill a big wolf. 3) You’ve done it! Historians, meanwhile, want to understand exactly how things happened, not just that they happened.

“Games reinforce that you have to get from A to B. In history, people made decisions and there was no guarantee that they’d make the decision they did,” says Gabriele, who specializes in medieval studies. But as a historian, “you’re trying to get across the messiness of history,” he says.

Players have long had many types of games to choose from. There are first-person shooters such as Battlefield, Call of Duty and Medal of Honor; real-time strategy games such as Age of Empires; turn-based strategy games such as Civilization; and third-person fighting and adventure games such as Dynasty Warriors and Assassin’s Creed. Each genre differs in the way it presents history to players.

First- and third-person games, for example, let players inhabit characters who live history as it happens around them, occasionally making history themselves. Games like these can spend a lot of time on the facts—weapons, dates, locations, and people—but don’t delve too deeply into why things happened the way they did, or on the motivations of the people involved. “They have one kind of fidelity to the truth, but allow you to make counterfactual actions, like assassinate Hitler,” says Leah Potter, a former college history teacher who now works at Electric Funstuff, the company behind Mission US.

But with game developers becoming increasingly sensitive to historical context and the ever-improving capabilities of modern technology, some educators see a real opportunity for games to expand their roles in the classroom.

“I encounter at least 10 students each semester that think history is boring,” says Luke Reynolds, a PhD candidate in history at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York who teaches undergraduates at CUNY-Hunter College. “Just giving them a little bit of interactivity will draw them in, in a way a textbook won’t.”

As an 11th grader taking US history in 2005, I was one of those students. The homework often involved reading chapters in a thick textbook—tested by weekly quizzes—but I couldn’t force myself to endure such drudgery for any period of time. Instead, I’d spend hours playing games. Then I’d spend hours more searching the internet for any information I could find about what I’d just seen on the screen, such as whether Joan of Arc’s comrade La Hire was as much of a beast as he is in Age of Empires, or if the fortifications on Omaha Beach really were as imposing as they appeared in Medal of Honor. Today, I can only vaguely picture the textbook (closed, as it spent most of its time), but I can vividly remember the games and what they taught me.

Aileen Nunez, who teaches global history to 10th graders at Hyde Leadership Charter School in the Bronx, doesn’t use video games in her class, but has seen how gaming can help students relate to historical events, particularly World War II. “A lot of the kids know the history from playing it in the games,” Nunez says. “When we’re talking about a specific area of the war, a lot of them actually know about it because they’ve played Call of Duty.”

World War II games, including the first three Call of Duty titles, saturated the market around the turn of the 21st century. Another franchise, Medal of Honor, rolled out 14 different games based on that era for a variety of gaming platforms from 1999 to 2007. I own five of them and have spent uncounted hours playing and replaying the oldest one of the bunch—Allied Assault—in an effort to critique the historical accuracy of the game and the actions of Lieutenant Mike Powell, the game’s protagonist.

Although the weapons, vehicles, landscapes, and timelines related to Powell’s travels through North Africa, Norway, and France are accurate, the messiness of history is often swept under the rug to drive the game’s storyline. Such sanitizing is particularly obvious in Allied Assault’s first mission, which takes place on the night of Nov. 7, 1942.

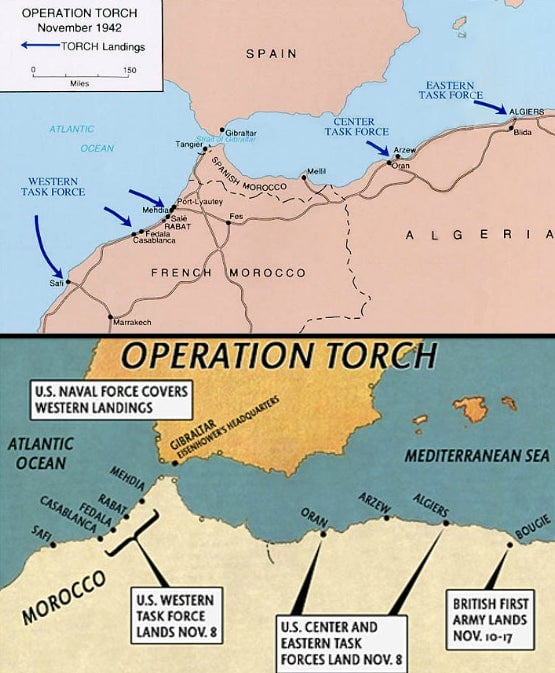

In the game, Powell and a small team of US Army Rangers sneak into a town outside of Arzew, Algeria, and sabotage artillery batteries that threaten the landing zone of Operation Torch—a real Allied invasion that began on Nov. 8, 1942. Powell’s only enemies throughout the game’s mission are Germans, and it’s easy to tell who’s a bad guy and who’s not. That wasn’t exactly the case for the real Allied soldiers who carried out the real Operation Torch (and who did not include Lt. Powell, who is a fictional character).

At the time, Algeria was governed by Vichy France, which controlled the unoccupied part of France but actively collaborated with Nazi Germany. Given France’s status as a US ally in prior wars, the Allies believed an American-led invasion would be met with little to no resistance. Instead, some Allied troops found themselves stuck in parts of the Vichy France—particularly the country’s capital, Algiers—where some French officers were sympathetic to the Allies and others were not. One Allied unit, the 168th Regimental Combat Team, was openly aided by French troops on the morning of Nov. 8, but found themselves under fire from those same soldiers a few hours later when a pro-Nazi officer took command, according to the US Army Center of Military History.

In the game, however, the player never faces that kind of uncertainty.

Taking liberties with history to drive the narrative or to simplify players’ experiences is common in mainstream games. And for the most part, gamers don’t seem to care, as long as the surface layer of facts are in order. This is especially true with Assassin’s Creed and Dynasty Warriors, both immensely popular game series based on historical events.

Many educators consider Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series difficult to use in the classroom because of how tightly its own elaborate, fictional storyline is woven with historical facts—if you’re a teacher, you have to spend precious minutes explaining why Pope Alexander VI probably wasn’t a member of a secret order trying to take over the world. Despite this, some have found it useful. Gabriele says one of his colleagues uses Assassin’s Creed II, based in Renaissance Italy, to take students on a virtual tour of Il Duomo di Firenze in Florence, Italy, a cathedral that, at the time, featured the largest dome ever built. Similarly, Assassin’s Creed I, set during the Third Crusade, includes a “pretty good” reconstruction of medieval Jerusalem, Gabriele says.

“I think where Ubisoft really succeeds is mapping their cities,” Reynolds says. “It really will give you a good feel of what it’s like to walk around the streets.” He points to the depiction of Revolutionary War-era New York City in Assassin’s Creed III, part of which has been destroyed by the 1776 Great Fire of New York. Roaming the in-game version of the city can show history students that Manhattan wasn’t always packed full of skyscrapers and apartment buildings, Reynolds says.

Francois Furstenberg, a US history professor at Johns Hopkins University, advised on that game and remembers how determined Ubisoft was to ensure New York and Boston were depicted as accurately as possible. “They were really keen to make sure that these buildings were where they had been in 1776,” he says. “It was important for them, for the brand, and for the sense of what the experience is, to make it as historically accurate as possible.”

But to history professors, most of these surface-level details aren’t tremendously important, he says. “’Was this building two stories or three stories?’” Furstenberg asks facetiously. “That’s not an interesting historical question.”

At a basic level, video games can be a springboard for teaching history, but they can also land a teacher in the shallow end of history education—oversimplification—or the deep end—treading water while tediously explaining every incorrect detail. “I think they’re great jumping-off points,” Gabriele says. “Unfortunately, when you’re teaching history, the past is kind of an esoteric concept.”

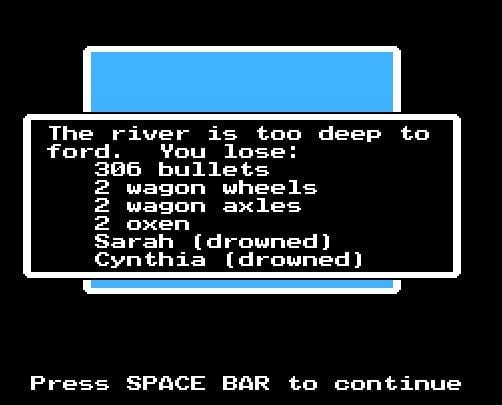

Robert Whitaker, a professor at Louisiana Tech University who also produces “History Respawned,” a YouTube show on history and video games, says he used the classic computer game Oregon Trail—publicly released for the first time in 1974—to supplement his lessons on westward expansion in a community college class he taught. Most West Coast-bound wagon trains in the mid-19th century totaled between 15 and 30 people—about the size of his class—so one session playing the decades-old game worked wonders to help his students understand how decision-making worked in a group of that size.

“It teaches the students not only what life was like trying to interact with group members on the trail, but it also taught them some of the possibilities of life on the trail,” Whitaker says. “They enjoyed the game because they remembered it from their childhood, but I think they came out of it more equipped to talk about that time period and also to critique depictions of that time period.”

Mission US, a free-to-play, browser-based game developed specifically to teach history to children in fifth through eighth grade, also seeks to drive deep discussions about history, its creators say. “Our hope really is that teachers are going to do all kinds of things with the game—not that kids are just going to play it and that’s it,” says Jill Peters, executive producer at WNET Channel 13, the PBS television station that had a hand in the game’s development.

The game, which currently features five stories from different periods of American history, is a collaboration of the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning at the City University of New York; WNET, the New York metro area public television station; and Electric Funstuff, a New York-based software company. Unlike many mainstream games, Mission US is not shooting for a mere veneer of historical authenticity.

“History comes first,” Peters says. “History drives the narrative.”

In each mission, players assume the role of fictional teenagers; Peters says it was important to show that “history doesn’t just happen to people wearing powdered wigs.” Students, she adds, have been “blown away” to learn that history happened to people their age as well.

Jackson, who uses the game with his 11th graders, finds the game is compelling enough to appeal to students older than its designated age range. One of his students, Assy Barry, who was born and raised in Benin, says the game helped her understand what happened and why it happened better than the textbook. “I feel like we learn more by getting engaged rather than just stating facts, and that is what these games allow us to do,” Barry says. “We get to experience it, be engaged, and see the results of our choices.”

Despite the drawbacks to using video games as a history teaching tool, they do offer unique benefits. Most basically, they offer a new way into the material—a means for teachers to teach to different learning styles in their classrooms. “We tried too long to make history classes kind of a one-size-fits-all approach based on textual analysis, and I think we could be doing much more to incorporate different types of media and different types of learning,” Whitaker says.

They are also particularly effective in showing students that history isn’t inevitable and that things easily could’ve turned out differently, Keulemans says—press the wrong button and you could lose a battle that was actually won. “Games are open in a way that for us, history is not.”

Of course, history is as much written by chance events as a given attempt at beating a video games. In 1918, the Red Baron, with 80 air combat victories under his belt, was killed by a single bullet, likely fired from the ground, that pierced his heart and lungs. T.E. Lawrence of Arabia fame retired after in 1935 after 16 years of military service—and died two months later in a motorcycle crash. “There are accidents in history,” says Joshua Brown, executive director of CUNY’s social history project. “It’s not simply determined by how many weapons you brought with you or how much food.”

“When most students approach history, they think that things were going to play out the way they were going to play out regardless of anybody’s individual actions,” says Whitaker. “That’s a really difficult idea to overcome, and I think video games help us do that.” They are, Whitaker says, a vibrant reminder that “the past isn’t a foregone conclusion.”