Americans gave away online privacy to advertisers long ago

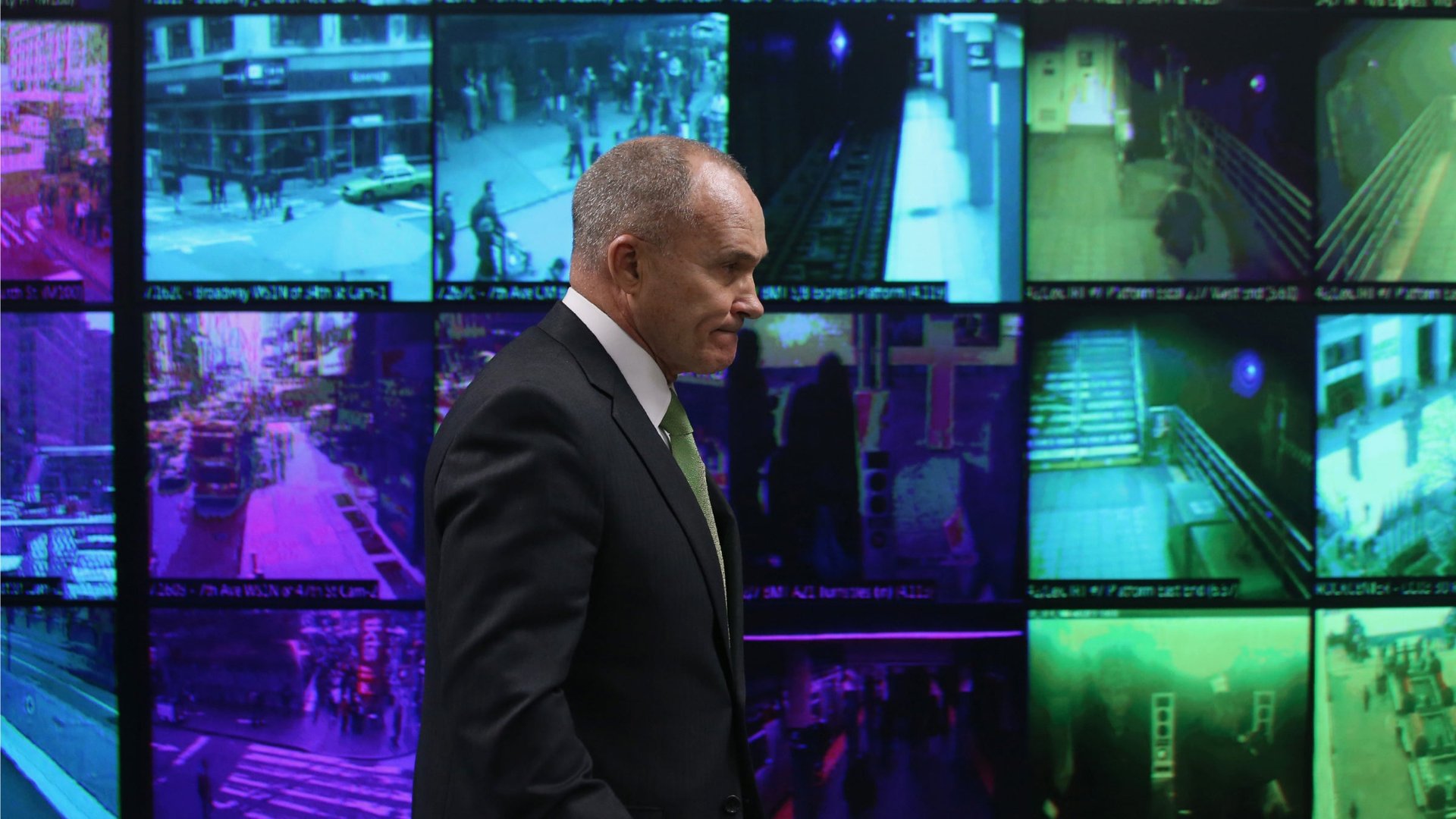

New stories surface every day detailing the National Security Agency’s administration of secret programs designed to keep the US “safe” in an era of internet communication and global networks. Having a strong opinion on any particular set of details would be premature.

New stories surface every day detailing the National Security Agency’s administration of secret programs designed to keep the US “safe” in an era of internet communication and global networks. Having a strong opinion on any particular set of details would be premature.

But allow me to offer this: Whatever abuses of privacy occurred, we remain entirely responsible for our reaction to them and the subsequent action taken by lawmakers. So far, in general Americans have been apathetic—the New York Times described the reaction as “a collective national shrug.” While sales of 1984 have spiked in the wake of the NSA reveal, Americans have basically told our leadership that the monitoring of personal communications is A-OK. If we look for a genesis of this unbelievable attitude, I believe we must look closely at the tech industry’s addiction to revenue models that cost end-users nothing except their privacy.

The conundrum of privacy in a digital era is that the more of it you give away, the better the service you’re using becomes. Facebook mines your friends and preferences to make your Newsfeed as interesting as possible. Foursquare analyzes your check-in data in order to give you recommendations when you visit new cities. Twitter routinely recommends new and interesting accounts based off of who I already follow, as do scores of other services—network effects are, after all, what makes these websites so useful in the first place.

In the interest of growing these network effects as quickly as possible, almost all new socially-oriented services are free. Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare, Google—never in their wildest dreams would they have thought to charge users for signing up. In lieu of subscriptions, these companies have one real alternative: advertising.

With the exception of the Super Bowl and Times Square, hating ads is an American tradition, and most advertising is met with an attitude ranging from begrudging acceptance to active avoidance. To combat this, the industry has rallied behind the idea of relevance, or ads so good that you’ll actually be excited to see them.

Relevant ads are obviously better than irrelevant ads—imagine how much collective time and money has been wasted on Viagra commercials—and the treasure trove of newly available data regarding our browsing habits is ushering in a golden age of relevancy. Relevant ads, however, come with a cost. After agreeing in its terms of service that Gmail may read your emails and store your searches, and that Facebook and Twitter can scan every word you post, you also agree that they can turn around and sell that information to advertisers.

It’s the complete ubiquity of data-enhanced ad targeting that, over and above previous government over-reach, has numbed Americans to the idea that their online lives are anything from private. This is not to say that online advertising is worse than government spying—it isn’t. But the constant, daily reminder that our information does not belong to us, courtesy of hundreds and thousands of “relevant” ads, has accustomed us to think that the government might as well spy on this information too. Advertisers are using our information to sell us crap we don’t need, so the government might as well use it to keep us safe, right?

I don’t know exactly what the government did, but I have the sense that none of our founders would be too proud of us for allowing them to do it. Just because online services sell our information to advertisers, it doesn’t mean that the government should have any natural right to it as well. We need to stop acting like they do and demand accountability.