Google took your drawings and taught its AI to sketch on its own

A few months ago, Google made a game called Quick, Draw!, where it supplied you with a word and you’d try to sketch it online. The game then used a neural network, a statistical approximation of how the brain learns, to identify what you were trying to sketch. It was like playing Pictionary with an opponent powered by more than a dozen high-powered data centers across the world.

A few months ago, Google made a game called Quick, Draw!, where it supplied you with a word and you’d try to sketch it online. The game then used a neural network, a statistical approximation of how the brain learns, to identify what you were trying to sketch. It was like playing Pictionary with an opponent powered by more than a dozen high-powered data centers across the world.

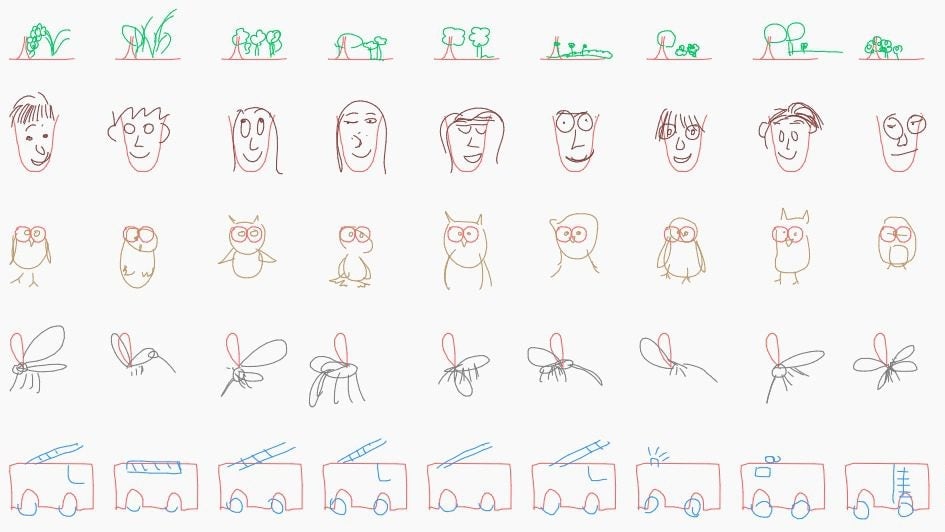

As people played the game, Google collected more and more examples of how humans quickly sketch common things, like owls, gardens, pigs, and yoga. So researchers took those examples and built another neural network, one that would mimic the way humans draw, that had the capability to draw a few ideas on its own. The network, called Sketch-RNN, learned to draw from more than 5 million sketches that people entered into the Quick, Draw! site, according to a Google paper by researchers David Ha and Douglas Eck.

“The goal of our research is to be able to train machines to draw and generalize abstract concepts in a manner similar to humans,” Ha tells Quartz in an email. “We think by training a neural network to understand and generate sketches that are similar to the ones that humans produce is a good starting point.”

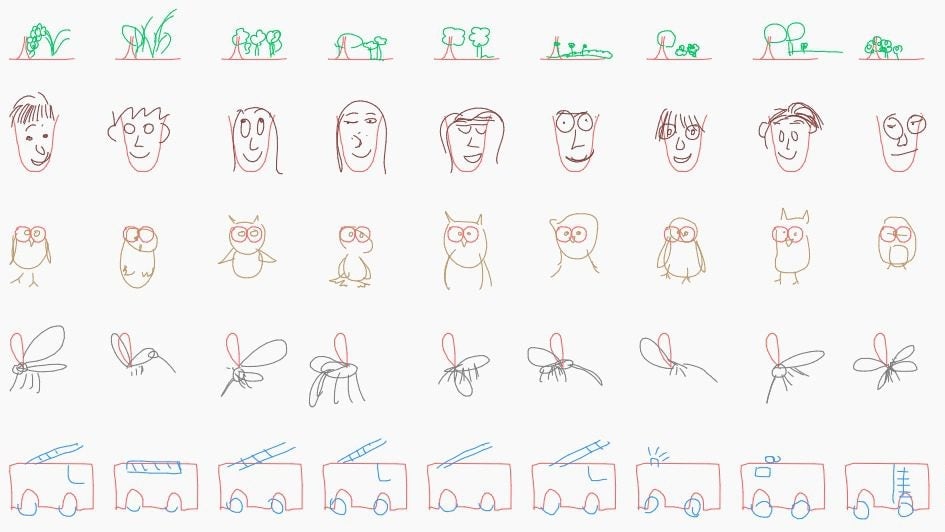

This new neutral network acts like a kid who wants to do everything it sees somebody else do. It takes a human-made drawing and thinks (but not really thinks) “I can do that too!” For instance, once it’s shown about 70,000 images of cat sketches, it can see a sketch that a human makes of a cat and then try to do the same thing, getting relatively close.

Crucially, the network isn’t just copying what it’s seen before, it’s actually generating its own attempt each time, even varying the details a little. It might add a whisker or a little tail, researchers wrote. This shows that the network actually knows the component parts of what “makes” a cat. Moreover, it will correct mistakes that humans make when sketching.

“When presented with a non-standard image of a cat, such as a cat’s face with three eyes, the reconstructed cat only has two eyes,” Ha and Eck wrote in the paper.

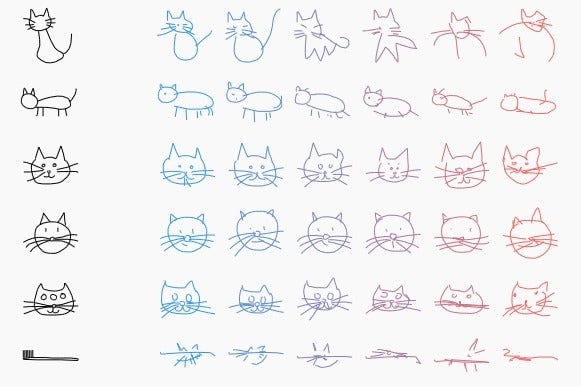

When only told what to draw, and not given anything to copy, the network was able to generate different variations of the same idea of “frog,” “cat,” or “crab,” with a similar accuracy to a lot of people with bad art skills, which makes sense, because that’s a majority of the data the network was trained on.

This work is different than a lot of other research on generating art, images, or video. Instead of looking at images as a set of pixels, the neural network considers the sketches as vectors —a mathematic expression of a shape. This allows the network to focus on how the idea is being expressed in shapes, rather than its size, color, contrast, and other information that varies when looking directly at pixels. To Ha, this is closer to how humans think.

“As humans, we don’t really think of images as 2D grids of pixels, but instead develop an abstract concept of what we see,” he says.

The researchers see this as potentially a powerful tool for artists. One of the experiments in the paper tasked the network with finishing sketches that the human had started drawing. They found that it was able to complete easy sketches like mosquitoes, oriented around where the original drawing had started, as well as firetrucks and owls.

In the future, this kind of creative AI could help suggest to artists or architects how to finish their drawings, or help beginners learn to draw. The researchers even suggest using this method to create wallpaper designs, or to help designers think about different ways to draw an idea.