We tracked Jeff Bezos’s use of “we” versus “I” over 20 years to see how he’s changed as a leader

There’s no denying Jeff Bezos’s ambition. Not only has the Amazon founder and CEO built a company worth $430 billion, Amazon has successfully expanded beyond e-commerce to artificial intelligence development, Oscar-winning film, and cashier-free brick and mortar shopping.

There’s no denying Jeff Bezos’s ambition. Not only has the Amazon founder and CEO built a company worth $430 billion, Amazon has successfully expanded beyond e-commerce to artificial intelligence development, Oscar-winning film, and cashier-free brick and mortar shopping.

But Bezos’s most recent letter to Amazon shareholders showcases a more subtle aspect of his evolution over the past 20 years. As his company has grown and Bezos’s personal prominence has soared, the pronouns that he uses to discuss Amazon’s strategy and success have changed as well.

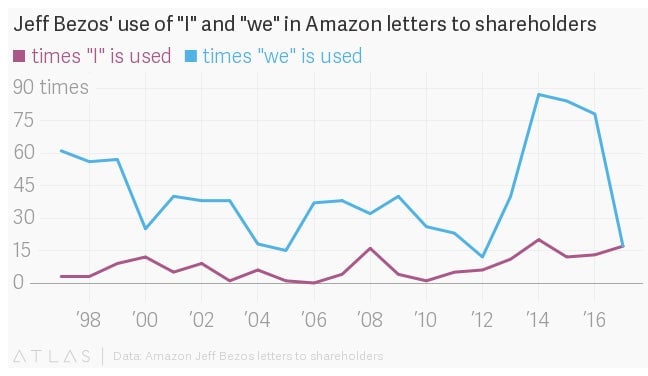

Our analysis of Bezos’s use of the pronouns “I” and “we” through his 20 shareholder letters show that, overall, he talks about himself a lot more than he used to—and uses group-oriented language a lot less. Here are the charts tracking his use of pronouns, beginning with his first shareholder letter in 1997:

In 1997, the year Amazon went public, Bezos used “I” just three times, and “we” a total of 61 times. In 2017, by contrast, he strikes a compelling balance: he uses 17 “I”s and 17 ”we”s.

Outlier years exist. Bezos’s use of “I” soared around the financial crisis, perhaps reflecting his desire to take responsibility for navigating the company through a troubled economy. And there are clear spikes in his use of “we” from 2014 to 2016, primarily because these letters were twice as long as every other year’s two- to-three page letter. (Amazon also experienced significant growth during these years, which Bezos explains in length.) But overall, the letters’ steady increase in “I” and decrease in “we” points to the solidification of Bezos’s status as a management guru.

It would be easy to quickly dismiss Bezos’s increase in “I” as evidence of an egotistical leader who started out sharing the company’s risks and now hoards credit, says Liane Davey, an organizational psychology expert and author of You First: Inspire Your Team to Grow Up, Get Along, and Get Stuff Done. Yet she says Bezos’s pronoun usage is actually quite laudable.

In his initial 1997 letter, Bezos declares his faith in Amazon’s rise by relying on team-oriented language: “Our goal is to move quickly to solidify and extend our current position while we begin to pursue the online commerce opportunities in other areas. We see substantial opportunity in the large markets we are targeting,” he writes. Listing Amazon’s management and decision-making approach, each statement starts with “We will.” Bezos only uses ”I” on the last page of the letter, when he writes, “The past year’s success is the product of a talented, smart, hard-working group, and I take great pride in being a part of this team.”

Emphasizing the inclusiveness of your company is an essential part of early-stage leadership, according to Davey. It’s a way to ensure that every employee feels they share responsibility for the success or failure of the company, and that they have a voice in shaping management and culture. Bezos’s use of “we” spikes in letters extensively describing Amazon’s success—like 2013, when he explains Prime, Prime Instant Video, Kindle, Fire TV, and more—which shows that his commitment to sharing credit for triumphs wasn’t just a facade, says Davey.

But when companies achieve wild success, the public inevitably attributes that success to individuals. Whether or not Bezos—or Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk—actively want to become management gurus is irrelevant, says Davey. American culture wants to believe the best businesses are built by geniuses with uniquely brilliant visions, especially when we believe that person can offer effective advice to the rest of us.

Bezos’s increasing use of ”I,” then, suggests that as Amazon grew, he came to recognize his responsibility not just as a CEO reporting to shareholders, but as a business leader. Shirking from the public’s desire to know his business philosophies could seem tone-deaf, even conceited.

In his most recent letter, Bezos uses ”I” to let readers in on his thought process. But he remains curious (“I’m interested in the question, how do you find off Day 2?,” he writes, “I don’t know the whole answer, but I may know bits of it.”) and non-prescriptive. He balances confidence with self-depreciation, explaining how he wasn’t awed by a major Amazon Studios pitch, but “disagreed and committed” rather than overriding his team’s enthusiasm. “Given that this team has already brought home 11 Emmys, 6 Golden Globes, and 3 Oscars, I’m just glad they let me in the room at all!” he writes.

Most importantly, when Bezos shifts to discussing the company’s overarching strategy and success, he shifts away from “I” to “we.” ”At Amazon, we’ve been engaged in the practical application of machine learning for many years now,” he writes, calling out the personal assistant device Alexa.

In this way, Bezos’s shareholder letters offer a useful management lesson. A company’s success is never an individual feat, so it’s crucial to spread the credit around. But it’s also important to keep in mind that when you’re a business leader, people want to know what you’re thinking. So feel free to indulge in some self-reflection out loud—but when it’s time to give props, embrace the “we.”

The original version of article incorrectly stated that Jeff Bezos was referring to Manchester by the Sea in discussing an Amazon Studios pitch. Amazon clarified that Bezos was not referring to that film, but to a different, unspecified Amazon original.

Follow Leah on Twitter. Learn how to write for Quartz Ideas. We welcome your comments at [email protected].

____________________________________________________________________________