“Abortion is never mentioned” in the Bible—a Christian ob-gyn on why choice is pro-life

To those working in reproductive rights in the US, doctor Willie Parker is a hero. “A colored boy from Birmingham,” Alabama, as his 1962, pre-Civil Rights Act birth certificate described him, Parker grew up in abject poverty, fourth of six children, raised by a fierce single mother. Against all of the obstacles his country stacked against poor, African-American boys and young men, he became a doctor. Parker progressively expanded the horizon of his dreams and ambitions. First, he aimed to get any education at all. Then he made it to college, summer school at Harvard, and eventually onto med school.

To those working in reproductive rights in the US, doctor Willie Parker is a hero. “A colored boy from Birmingham,” Alabama, as his 1962, pre-Civil Rights Act birth certificate described him, Parker grew up in abject poverty, fourth of six children, raised by a fierce single mother. Against all of the obstacles his country stacked against poor, African-American boys and young men, he became a doctor. Parker progressively expanded the horizon of his dreams and ambitions. First, he aimed to get any education at all. Then he made it to college, summer school at Harvard, and eventually onto med school.

It’s perhaps because of all those obstacles that he became a crusader. After years as an ob-gyn, in 2005 he had what he calls his “come to Jesus moment.” As a devout Christian, he realized he could not justify his choice to not perform abortions—not as a doctor, and not as a believer.

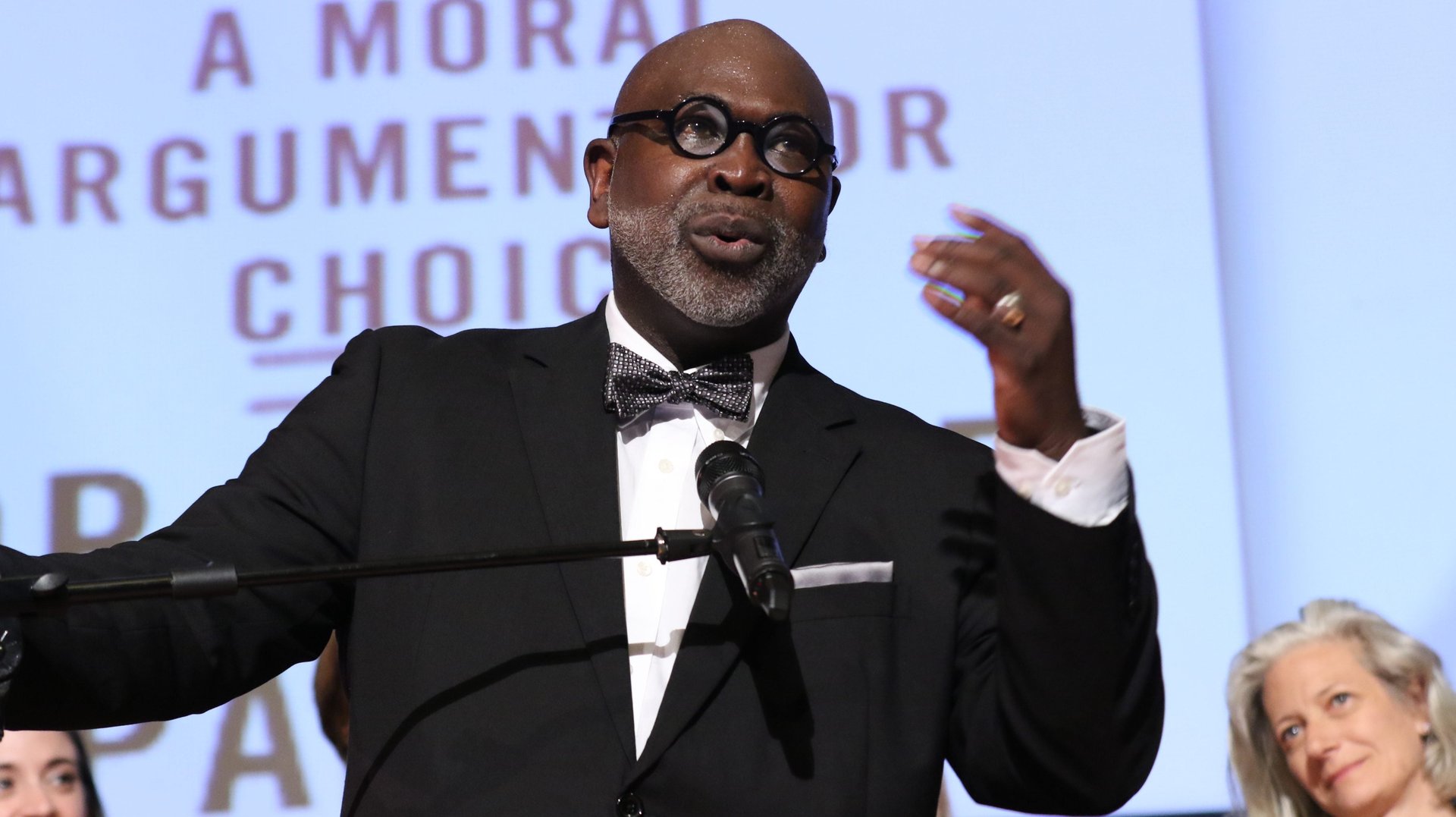

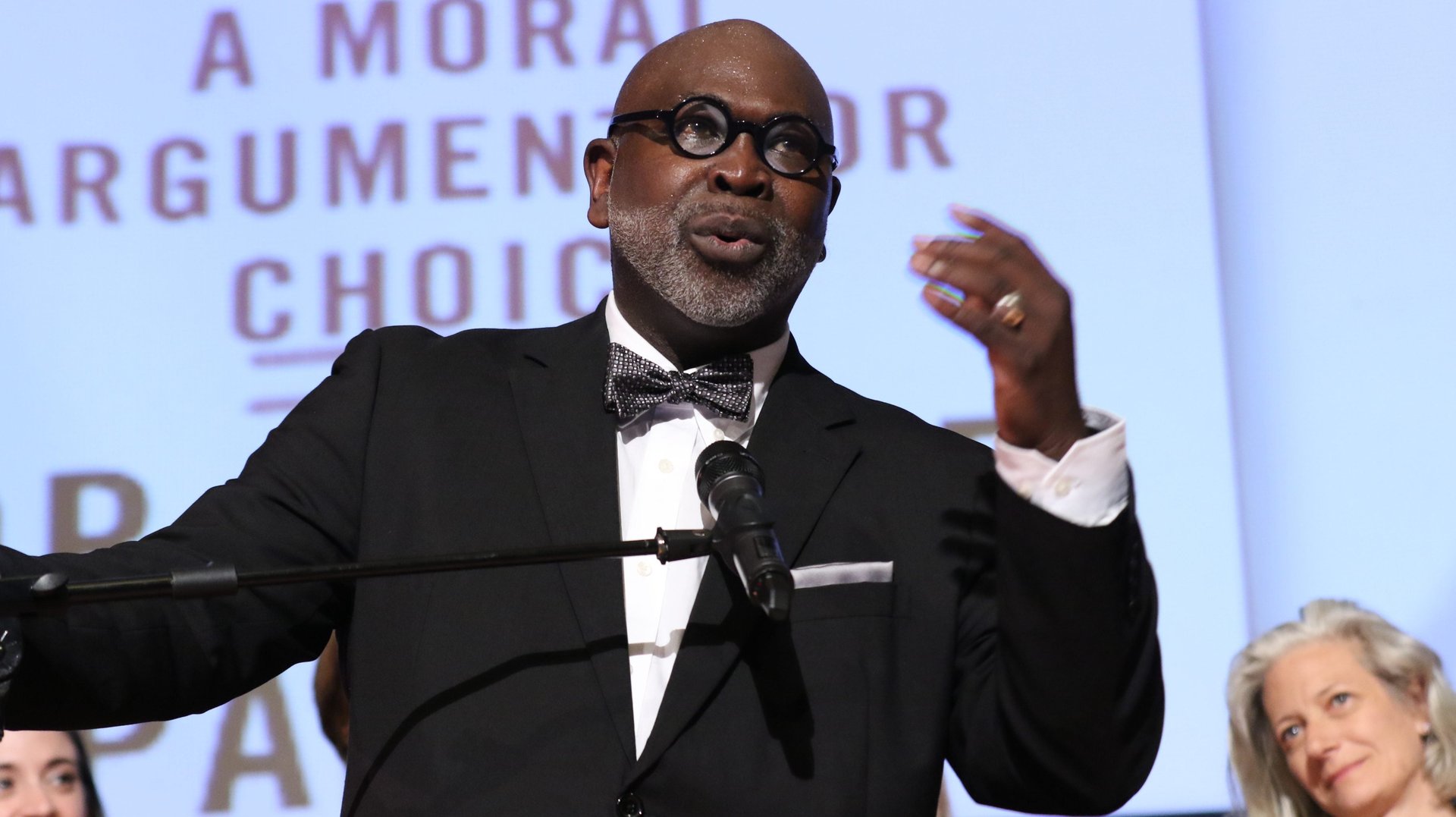

Since then, he’s been on the front line of what in the US is a war, and not just a legal one. While over 200 state laws have been passed in the past decade to try and curtail the right to abortion, 11 health practitioners, including Parker’s own mentor, Dr. George Tiller, have been murdered by anti-abortion activists. ”No one on earth expects a large, bald black man in sweats and a baseball cap to be a doctor at all, let alone one of the last abortion doctors in the south,” Parker writes in his memoir Life’s Work: a Moral Argument for Choice. With courage and just enough lightness, he does not let threats deter him or racist insults provoke him. He continues providing safe and compassionate abortion care to the women who need it in the southern states where they are least likely to see their rights honored—Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi.

As the Trump administration moves forward to cut funding to clinics that provide abortions—the main providers of reproductive care and education for millions of American women—and opposes support for women’s reproductive rights at home and abroad, Parker’s book provides a tight moral and religious case in favor of choice. It has the potential to speak to an audience far beyond those who are pro-choice.

As a doctor and as an advocate (Parker chairs Physicians for Reproductive Health), Parker debunks the myths around abortion with scientific precision and moral clarity, stripping away political interests, social prejudice and religious misconceptions to show it exactly for what it is, a medical procedure that offers women control over their own bodies. The scientific rationality with which he speaks about the practical, routine elements of his work are educational and eye-opening. Yet what’s most poignant about his book is how Parker demonstrates that he has made his medical and ethical choices, not despite his faith, but because of it.

For Parker, the moral and religious arguments against abortion are misguided at best: The will of God, he says, manifests itself in human’s free will. That extends to the freedom to choose whether or not to take part in the reproductive process, a divine freedom accorded to women as it is to men, regardless of their biologies.

“Decision-making should not stratify by gender,” Parker told Quartz, “and so if the most essential thing is to men so to be self-determining, and to be able to make complex decisions, women are no less capable of that.” Yet, as he writes, abortion is subject unparalleled social and government oversight and stigma, something that finds no equivalent in medicine. “By accidental biology, the procreation process plays out in the body of a woman,” the writer told Quartz, so “if women have equal agency to men, that process should not trump the ability to be self-governing, to have bodily integrity, or moral authority to make decisions about her body, including reproduction.”

In the US, one in three women have an abortion in their lifetime—and fewer than 5% ever regret doing so. Anti-abortion activists describe women who seek or contemplate abortion as full of doubt, misery, and regret. Parker says his experience is quite the opposite. He serves women who overwhelmingly know exactly what they want, and why, and are capable of making the choices they need to make with rationality and conviction.

“How can a pregnancy be more important that the woman herself?” Parker asked rhetorically during the interview. Any attempts to force a woman to carry forward a pregnancy she does not wish to have denies rights to a life that already exists. Limiting a woman’s right to self-determination renders the label “pro-life” disingenuous. Parker highlights how abortion is exploited as political currency to get votes, most notably in the election of 2016 when US president Donald Trump turned anti-abortion only when he sought to the Republican nomination.

Parker traces how opposition to abortion rights has become an “effort to save a patriarchy that is in its last vestige as a society becomes more diverse, with gender identity, race, class, religious identity.” In that, he doesn’t spare just conservatives politicians and their supporters. He takes on religion, too.

“In the world of the Bible, bearing many children was a woman’s most important job,” writes Parker. Yet “in that ancient cultural context, however, abortion is never mentioned…The death of a fetus is regarded as a loss but not a capital crime. Throughout Jewish scripture, a fetus becomes human when—and only when—its head emerges from the birth canal.” The New Testament doesn’t mention abortion at all. Thus, for Parker, the idea that life begins with the mere meeting of sperm and egg is offensive to God.

What he calls a “theology of abortion” is an appeal to religious people of all faiths to look beyond what they are taught by the patriarchal ranks of their churches:

“[I]f you set aside the idea that God is like Siri, telling you to go left and go right, then the whole business is sacred. All of it. A pregnancy that intimates a baby is not more sacred than an abortion. …The God part is in your agency. The trust—the divine trust—is that you have an opportunity to participate in the population of the planet. And you have an opportunity not to participate…The process is bigger than you are. The part of you that’s like God is the part that makes a choice. That says, I choose to, Or, I choose not to. That’s what’s sacred. That’s the part of you that’s like God to me.”

Parker uses his personal journey to shed light on an often foggy matter with compassion and understanding. He speaks about finding inspiration for his work, and life, in Martin Luther King Jr.’s work, learning from him “not to be compassionate by proxy.” He identifies a thread of radical solidarity that runs through all civil progress—be it for race, gender, or income equality.

“My decision to go home and to practice was informed by the reality of people who look like me,” he explains.

Parker understands oppression in its most pervasive and insidious forms—masked as a right to suppress, determined to blame the victim. In this light, being able to provide abortions for the women who need it most is nothing more, and nothing less, than a form of social justice.