The new growth industry in Africa is Muslim tourism

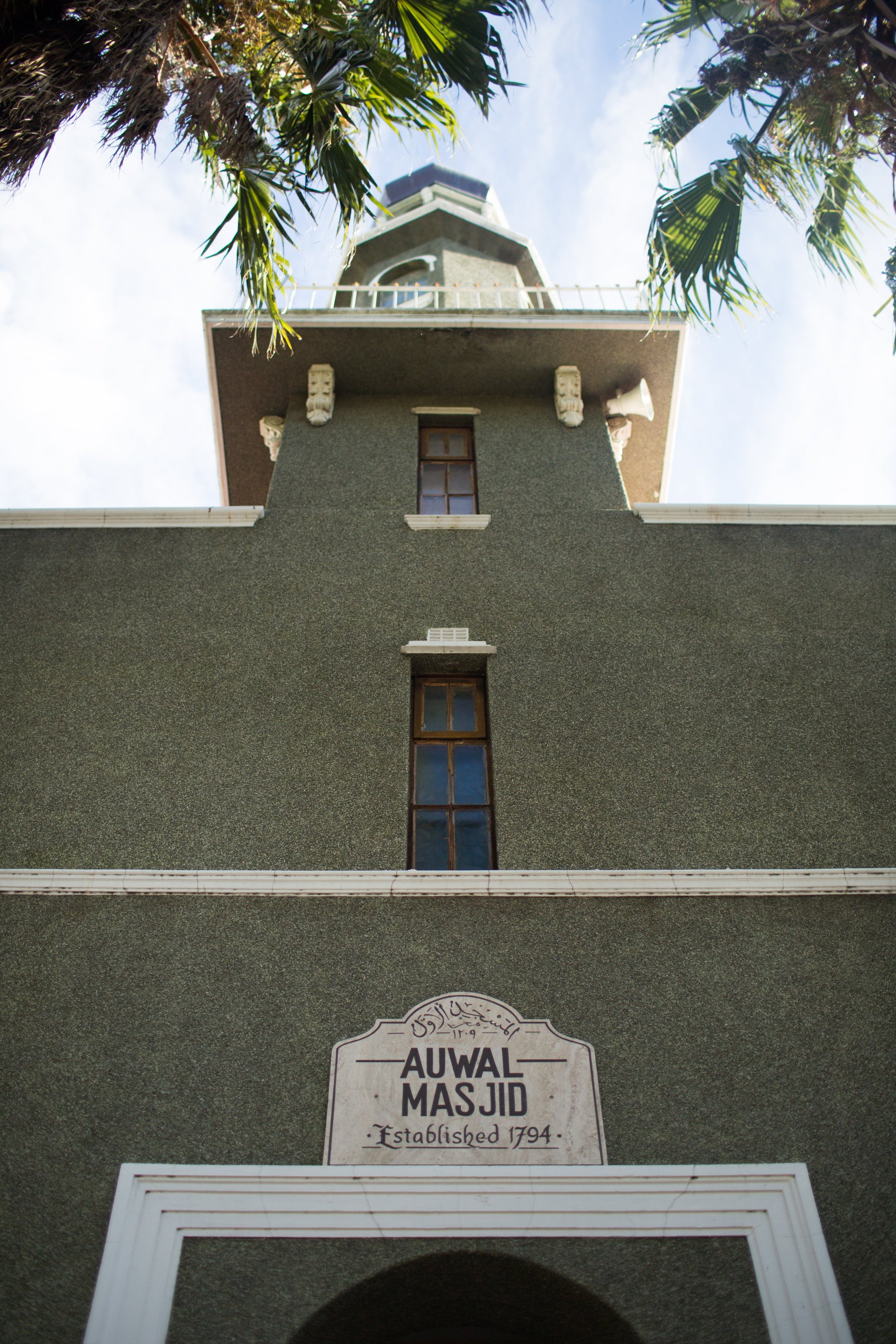

Islamic Travels and Tours is a boutique agency tailored to attend to the complete needs of the Muslim traveler in South Africa. In addition to organizing shark cage dives, whale watches, and bungee jumps, it will plan honeymoons for Muslim couples, arrange visits to a Muslim-owned predator park in Johannesburg, and schedule tours of South Africa’s first mosque, built in Cape Town in 1794.

Islamic Travels and Tours is a boutique agency tailored to attend to the complete needs of the Muslim traveler in South Africa. In addition to organizing shark cage dives, whale watches, and bungee jumps, it will plan honeymoons for Muslim couples, arrange visits to a Muslim-owned predator park in Johannesburg, and schedule tours of South Africa’s first mosque, built in Cape Town in 1794.

It will arrange tours of Soweto and trips on safari, and leave room on its clients’ itineraries for ritual prayer and dinners adhering to religious dietary laws. It will even match clients with local host families who share their religious background, giving tourists a chance, Islamic Travels owner Khalid Vawda says, to solidify their experience of South Africa and “see what life is like [for] an average Muslim working family.”

What you won’t find advertised on Islamic Travels’ website: excursions to vineyards, casinos, and nightclubs—staples of typical South African tour operators, but not activities that many Muslims would care to be associated with.

Vawda, a practicing Muslim from Johannesburg and an intrepid traveler himself, started his business in 2015 after realizing that traditional travel firms were overlooking a big opportunity. “Halal tourism,” as the growing niche is known, is being driven by a rising Muslim middle-class population that is well-educated, with disposable income and access to travel information. An estimated 117 million Muslims traveled internationally in 2015, according to the 2016 MasterCard-Crescent Rating Global Muslim Travel Index. That number is expected to grow to 168 million by 2020, with travel expenditures exceeding $200 billion.

But where some businesses see opportunity, others see danger. Donald Trump’s attempts to turn away visitors to the US from seven Muslim-majority countries, and to ban laptops aboard flights from several North African and Middle East countries, threatens to cut the US off from a growing opportunity to court Muslim tourism dollars, even from people who don’t live in countries the travel restrictions would cover. In February, the head of the World Travel & Tourism Council told the Boston Globe that the loss could be on par with the hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue he estimates was lost in the decade after the 9/11 terrorist attacks because of “strict visa policies and inward-looking sentiment.”

As Muslim travelers explore more welcoming destinations, Africa stands to benefit.

In Africa, Muslims mainly prefer to visit countries in North Africa like Morocco and Egypt, which have Islamic traditions, institutions, and cultural artifacts. Both countries are members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), an intergovernmental collective of 57 Muslim nations on four continents. But even Muslim-minority countries like Kenya, Ghana, and Tanzania are positioning themselves as places of halal tourism.

In Kenya, where tourism plays an important role in generating employment and foreign-exchange earnings, tourism officials plan to roll out standards by 2018 for certifying hotels and restaurants that meet halal standards to cater to Muslim tourists. Its cabinet secretary for tourism, Najib Balala, has suggested hiring Muslim-travel brand ambassadors and that Kenya join the OIC as an “observer” nation to better market itself to Muslims.

The most popular destinations for Muslims today include the United Arab Emirates, Malaysia, Turkey, and Jordan, according to data from Thomson Reuters. Lebanon, Iran, and Bahrain also attract many visitors. In the non-Muslim world, halal tourism is heading to places like Singapore, Thailand, Japan, and the United Kingdom—some of which have adopted Muslim visitor-friendly policies. Mastercard’s Muslim travel index shows that many countries outside of the OIC are moving up the ranking at a faster pace than their Muslim counterparts, reflecting faster growth in Muslim tourism.

South Africa has positioned itself as a regional hub for Islamic investment and travel, despite less than 2% of its population being Muslim. The country is one of the top five non-IOC countries most visited by Muslim travelers.

Local platforms like Stay Halaal offer travelers accommodation, sight-seeing activities, and food options. Local outlets of major international franchises like McDonald’s and Burger King are in many cases halal-certified. The Cape Town chapter of the nation’s hospitality association is working with Crescent Rating, a halal accreditation service, to audit the city’s facilities and run workshops to help businesses attract Muslim travelers.

Vawda says that steps by the local hospitality industry to accommodate travelers from different cultures have helped to boost his country’s image with travelers globally. South Africa’s major cities—Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban—remain the most visited cities in Africa, according to the MasterCard Global Destination Cities Index, and the country boasts the most hotels in sub-Saharan Africa. A diversity of services means clients are able to “shoot for any budget” for their travel, Vawda says, whether they are coming from Malaysia, Singapore, India, or the US.

The tourism sector in other African countries isn’t as developed. To meet the growing need, investors are looking at markets that have potential to develop halal-friendly hotels. Chris Nader is the vice president for development for Shaza Hotels, an independent five-star hotel management company based in the UAE. The company helps manage halal-friendly properties on behalf of investors and owners. After developing hotels all across the Middle East, Nader says the company is shifting focus toward expanding the brand in southeast Asia, Europe, and Africa.

“We know that there are investors in these markets who are keen to own a hotel,” Nader says. One opportunity is to develop halal-compliant lodges in popular safari destinations across Africa, he says.

This month, a startup called Muzbnb plans to launch an Airbnb-like service to let Muslim proprietors rent to Muslim travelers around the world. The platform would provide travelers with guidance on properties with a prayer space or proximity to a mosque, and have recommendations for nearby halal dining options. Co-founder and CEO Hadi Shakur hopes to enrich the experiences of Muslim travelers and to have them feel treated not “as a liability, but rather as an asset.”

Muzbnb says it has received listing requests from several African countries including Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Tunisia, Tanzania, and South Africa.

Overcoming challenges

Before it becomes more profitable in Africa, the halal tourism business has to overcome some challenges. The cost of obtaining certification, restructuring facilities, and training employees and chefs on how to attend to Muslim guests can be prohibitive to hotel operators and service providers. Local hospitality sectors also face losing revenue from alcohol sales.

What constitutes “halal” is subjective; there are no unified, global halal standards. Without established guidelines and proof of strict compliance, orthodox travelers could be put off.

“Halal certification is not just about the product, but about the process,” says Anna Maria Aisha Tiozzo, president of the World Halal Development certification center in Italy. For instance, hotels have to be careful not only in how they prepare food as prescribed by Muslim law but in where they source their meat or other ingredients, Tiozzo says. Without uniform standards, it will be hard for different regulators in different nations to follow the certification criteria, let alone supervise how businesses conduct their operations in their respective cities and countries.

Another key challenge is the looming threat of terrorism, which has battered tourism markets in Tunisia, Egypt, and Kenya.

But the even bigger obstacle for halal tourism providers in Sub-Saharan Africa is obtaining financing and convincing investors that the market is ready. Nader says that most investors interested in financing halal tourism want to “put their money in already saturated markets” in the Middle East or North Africa. This, he says, creates “difficulties in bridging the gap between statistics, demand, and people who have the money that can invest.”

To overcome the cash shortage, governments might look into the Islamic finance industry for investment. Islamic finance, which operates on a profit-sharing basis rather than collecting interest, or usury, has proven to be an effective tool to raise capital globally and finance development projects, according to the World Bank. Sub-Saharan Africa countries like Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo have all tapped into Islamic finance, with some even offering sukuk or Islamic bonds.

If Islamic Travels’ early success is any indication, there’s money to be made in halal tourism in Africa. Vawda says his company has been profitable for the two years it’s been in operation, and is getting more and more calls from travelers and agents overseas.

“The business is still in its infancy,” Vawda says, “but the potential is immense.”