This is the last year a car will be made in Australia

Sydney, Australia

Sydney, Australia

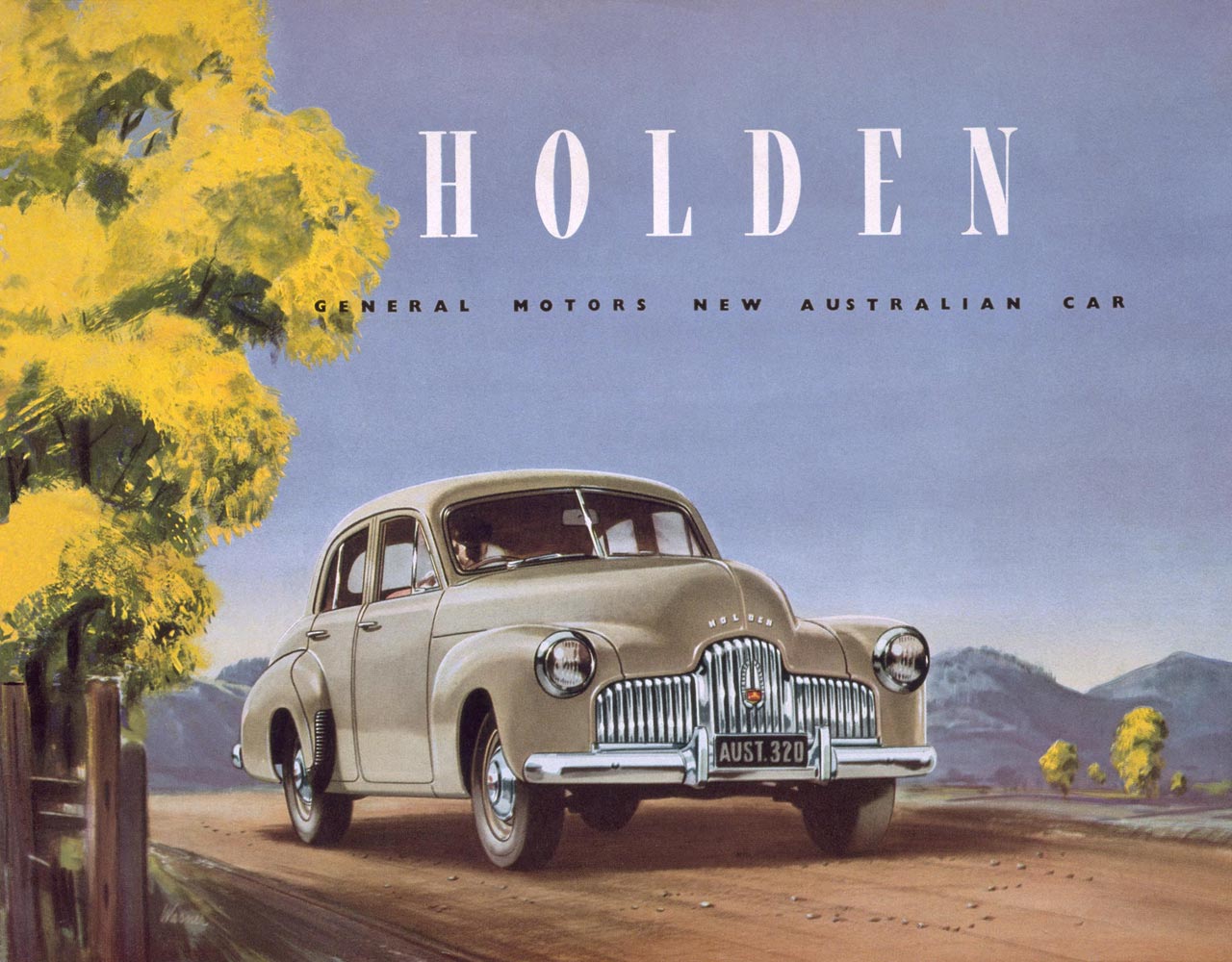

It’s farewell to ”Australia’s Own Car” when General Motors’ Australian unit Holden closes the door on its factory later this year. And with that, the country’s almost century-old auto-manufacturing industry will officially come to an end.

Holden was and remains an Australian icon, having started as a local company before eventually catching the eye of GM. Its cars were the choice of fair-dinkum rev heads and police alike. As such its closure is momentous for both the national psyche and economy, exemplifying the country’s shift to a services-dominated economy. But while Donald Trump promises to bring back manufacturing jobs to the US and make America a more protectionist economy, Australia has by and large embraced its economic choices—the country, after all, has now gone nearly 26 years without a recession.

“Making things is officially over. [Australia] is now a country whose economy is about doing things and helping people,” argued Jason Murphy, an Australian economics commentator.

In Australia, phasing out the auto-manufacturing sector has been an active choice. Australia was one of just 13 countries in the world capable of building a car from scratch—at its peak, Australia produced almost half a million cars in 1974, but output never recovered to those levels.

Australia decided to stop subsidizing the industry and slowly pull the plug instead. From the 1980s, successive Australian governments pursued a policy of “managed decline” to “consolidate the industry and make the end of the car industry economically and politically palatable,” said Tom Conley, a lecturer in political economy at Griffith University in Queensland. “It was a bit like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.”

Australia’s Productivity Commission calculates Australian taxpayers spent A$30 billion (US$23 billion) on subsidies for the local car industry between 1997 and 2012. But with reduced, or in many cases no, tariffs, “Australia became flooded with foreign cars that were either cheaper to buy than local models, better equipped, or both,” motoring journalist Joshua Dowling argued. “Australia was the only country in the world to manufacture cars and not have some form of protection for its local industry.”

Once the Coalition government led by prime minister Tony Abbott announced an end to long-running subsidies in 2014, the writing was on the wall for companies that made cars in Australia—including Toyota. The Japanese giant, which had been the nation’s biggest automaker, announced that same year it would stop making cars in Australia. Max Yasuda, Toyota Australia president and CEO, described the decision to leave as “one of the saddest days in [Toyota’s] history worldwide.”

Of course, turning off the industry’s life support hasn’t been painless for Australia. John Spoehr, director of the Australian Industrial Transformation Institute at Flinders University in Adelaide, estimates the closure of the industry will mean 200,000 job losses, wiping off around A$29 billion, or 2%, of the nation’s GDP.

The blow is softened by Australia’s unique advantage of having an abundance of natural resources while also being relatively close to China. As many other economies suffered from the ravages of the great financial crisis, Australia, riding the once-in-a-generation mining boom, saw its living standards soar as China’s economic development took off in the last decade. That all helped make the decline of the manufacturing industry “economically palatable,” said Conley.

And while some lament that the opening of Australia’s economy over the last 35 years has facilitated the decline of its auto-manufacturing industry, it has also made Australia one of the most affordable places to buy a car, as consumers benefited from cheaper foreign offerings—at the expense of inefficient local manufacturers.

Australia’s openness to trade has also transformed the nature of its economy. In 1973, the number of Australians (pdf, p. 5) employed in the services sector was 58%. Today, services employ four out of five Australians and represent 70% of Australia’s GDP. In contrast, the mining sector represents 7% to 8% of GDP.

But Australia’s rev heads need not worry, said Royce Kurmelovs, author of a book about Holden.

“Holden will still sell cars here, only they’ll be made in Germany.”