Hebrew was the only language ever to be revived from extinction. There may soon be another

“All things must pass,” wrote Ian Roberts, a Cambridge University linguist, in a book published last year. “This is as true of you and me as it is of everything we know. It’s also true of languages: Avestan, Etruscan, Tocharian, Gothic, Cornish, Klamath, Yurok, Akkadian, Sumerian, Dyirbal. Gone.”

“All things must pass,” wrote Ian Roberts, a Cambridge University linguist, in a book published last year. “This is as true of you and me as it is of everything we know. It’s also true of languages: Avestan, Etruscan, Tocharian, Gothic, Cornish, Klamath, Yurok, Akkadian, Sumerian, Dyirbal. Gone.”

There are 7,000 languages spoken in the world, and half are seen as at high risk of dying out in the coming century. History records just one that has been brought back to robust life: Hebrew, revived by eager Zionists more than a century ago on the basis that a state required a unifying language as well as a territory.

Now, however, another is on the road to revival. And remarkably, it’s one of the ones Roberts included in his esoteric list of long-dead tongues: Cornish, the language of the southwestern tip of England.

Most language experts are unaware of the extent of this renaissance. Cornish is one of nine languages that Ethnologue, the standard reference guide to all the world’s languages, lists as “reawakening”. These languages have “no known L1 speakers, but emerging L2 speakers”, which means no native speakers, but a few adults who have acquired the rudiments of the language later in life. Yet, as I learned on a recent visit to Cornwall, and previously unbeknownst to the data-gatherers at Ethnologue, Cornish in fact now has several adult native speakers—L1s—as well as perhaps several hundred fluent second-language speakers.

What makes this especially remarkable is that Cornish is thought to have had no native speakers or any other form of regular use for more than two centuries. That sets it apart from Manx, the indigenous language of the Isle of Man and the only other language to have been taken off the list of extinct languages kept by UNESCO, the UN’s cultural body. Manx was only briefly dead; its last native speaker died in 1974, and revival efforts have been in full swing for much of the time since.

It also distinguishes Cornish from Hebrew, which, though not spoken as an everyday tongue for some 2,000 years, was never truly extinct—it was used by millions of Jews as a language of prayer, literature, commerce, and study throughout their history. If Cornish can reestablish itself robustly it would show that linguistic resurrection doesn’t require the fervor that comes with a religion or state-building. Instead, with minimal and intermittent support, a few true believers can do the trick.

A Celtic heritage

Cornish, part of the Brittonic branch of the Celtic family, is closely related to Welsh and Breton, the language of Brittany. (The other branch includes Manx, Scottish Gaelic and Irish.) The languages’ distribution reflects an ancient diaspora. The Anglo-Saxon invasion of the sixth century pushed Celtic speakers in the south of Great Britain to the west, to the north, and across the sea to Brittany and Galicia.

For centuries thereafter the Celtic spoken in Cornwall and in Brittany was virtually the same, but in time they diverged. Cornish is thought to have reached its peak number of speakers in the 13th century, and most historical Cornish literature was written in the centuries just after. The longest works were the “Ordinalia”, three Christian mystery plays. There were also 13 mid-16th-century Catholic homilies translated into Cornish by John Tregear and collaborators. By this time, says Allan Kent of Open University, knowledge of Cornish was already in sufficient decline that Tregear, writing in haste, inserted English words into the text, possibly ones he could not recall in Cornish but hoped to insert later: “Ima an profet Dauit in peswar vgans ha nownsag psalme ow exortya oll an bobyll the ry prayse hag honor”.

The homilies were part of Catholic Cornwall’s resistance to the Reformation, with its English-language church services. But the “Prayerbook rebellion” was squelched, and the language was beaten back to a south-western corner of the peninsula. The number who could look an uncomprehending Englishman in the eye and say “Meea navidna caw zasawzneck”—“I will speak no Saxonage”—eventually dwindled to nothing.

It is usually said that Dorothy (“Dolly”) Pentreath, who died in 1777, was the last native speaker. Today’s enthusiasts for the language eagerly point to evidence that it continued to be spoken among farmers and fishermen, and perhaps among the Cornish diaspora. A conference held in September 2016 in the Cornish town of Penryn heard word of an Australian matriarch recorded reciting a memorised Cornish prayer in 1970. Jenefer Lowe, an independent scholar of the Celtic languages, says that when she began teaching enthusiasts in the 1980s she was surprised by what they already knew: “These women would come out with these things that were pure Cornish.”

Nevertheless, Cornish was thought dead enough in the 19th century for people to start taking an interest in bringing it back to life. Henry Jenner, born in 1848, was the first person to try. In 1904 he published a handbook of the language, not so that antiquarians could study its texts passively, but so all Cornishmen could learn to read, write and speak it. It remained, though, a very fringe interest until the 1970s and 1980s, when a cadre of Cornish enthusiasts yoked a political taste for centrifugal autonomy to a passion for a neglected language.

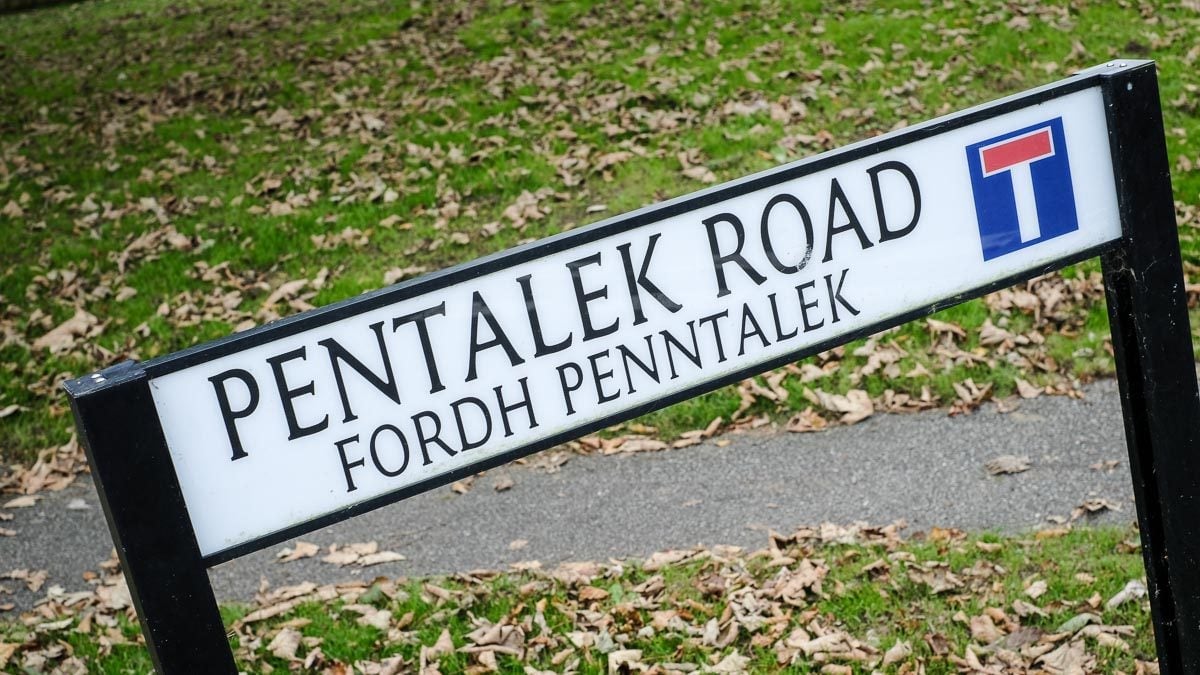

A campaign begun in the 1990s culminated, in 2002, with the British government’s recognition of the language as covered by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages—an agreement by members of the Council of Europe (a democracy watchdog) which requires governments to support and protect small languages. Funds flowed to organizations under the umbrella of the Cornish Language Partnership (CLP) to write textbooks, adjudicate spelling disputes, create terminology for the modern world, support teacher training, fight for a place in primary schools, and so on.

Getting funding, though, required a standard written form. In the 1970s Ken George, an activist, proposed a new spelling system meant to be easier than that which Robert Morton Nance, a student of Jenner’s, had come up with two generations earlier. But before long other systems were established, their proponents in bitter competition despite the systems’ by-now ironic names: Unified, Common, Unified Revised and so on. They argued about which period (middle or late) to base the spellings on, whether to keep historical irregularities, how many borrowings (especially from English) to allow. Some of the antagonists are still hardly on speaking terms.

In 2008, after two years of meetings, a new compromise version was proclaimed, the “Standard Written Form” (SWF). But the official support it was meant to make easier has proved short-lived. In April 2016, the British government, as part of its push for a balanced budget, eliminated the £150,000 (now $188,000) a year funding for Cornish, rendering the CLP a shell, and leading to a lecturing report on minority rights from the Council of Europe in February.

A Cornophone with a microphone

For now, Cornish relies again on nothing but its devotees’ enthusiasm. But such enthusiasm can produce surprising successes. The handful of adult native Cornish speakers are proof of this. Their parents were idealists who raised their children to speak Cornish from infancy, despite not being native speakers themselves.

Ray Chubb is one such parent. He hosted Cornish-speaking gatherings at his house from the 1970s on, and at some point decided that his sons, born in 1983 and 1985, should understand the proceedings. He bought a book on raising bilingual children and followed its recommendations faithfully. He notes that early on, the boys assumed that Cornish was the only language the visitors spoke. The first time one of the children heard one of them speaking English, “his jaw dropped.” To this day, they speak only Cornish with their father.

Another Cornophone, this one with a microphone, is Gwenno Saunders. After some success in an English-singing, indie-pop group, The Pipettes, she now sings and writes songs exclusively in Welsh and Cornish, which are about as closely related as Spanish and French. Here is a recording of her singing a song called “Amser” (Time) in Cornish.

Her father, Timothy Saunders, is a poet who spoke only Cornish to Gwenno and her sister as they were growing up. It was not her only language; her mother spoke Welsh to her, and she went to Welsh-language schools. Today she speaks Welsh to her son, though her grandfather speaks to him in Cornish.

Saunders, too, recalls a community of Cornish-speaking friends around her father, and was completely unaware of being one of the language’s only living native speakers. She says her fans are even more enthusiastic and curious about her work in Cornish than they are about her Welsh songs. For her, “using [Cornish] in my songwriting has been the most freeing, liberating experience.”

Pop music, like the eager handful of Cornish-users on social media, may boost the language’s relevance to the young. Mike Tresidder, formerly of the CLP, insists it must not be seen as “the preserve of retired schoolteachers”. At the conference in Penryn most people were indeed older; but a few young scholars joined them, their Cornish sometimes halting, sometimes quite comfortable. Next to presentations on Tregear’s Homilies, they discussed apps for teaching Cornish and tools for automatic translation.

One of the conference’s running themes was what to do now that government cuts have got rid of the few full-time jobs fighting for Cornish (Lowe and Tresidder both previously had government-funded jobs). Volunteerism and donations seem the only way forward, but they are not as forthcoming as the enthusiasts would wish. Tresidder decries the “passive” attitude of many in Cornwall. The activists envy the Isle of Man, which is partly self-governing; the Manx can decide for themselves whether their language is a luxury or an essential cultural heritage. Cornwall has no such autonomy, and fears being merged with neighbouring Devon; the dread word “Devonwall” is enunciated with scorn in Penryn.

From the mouths of babes

If Cornish is to have a future, more parents will have to raise their kids speaking it. Emilie Champliaud, a Frenchwoman married to a Cornish-speaking Welshman, is doing her part. An enthusiastic language-learner, she sought, however improbably, to learn Cornish on her arrival there. In 2010, she opened a small creche in Camborne, where she speaks only Cornish to the children (including three of her own).

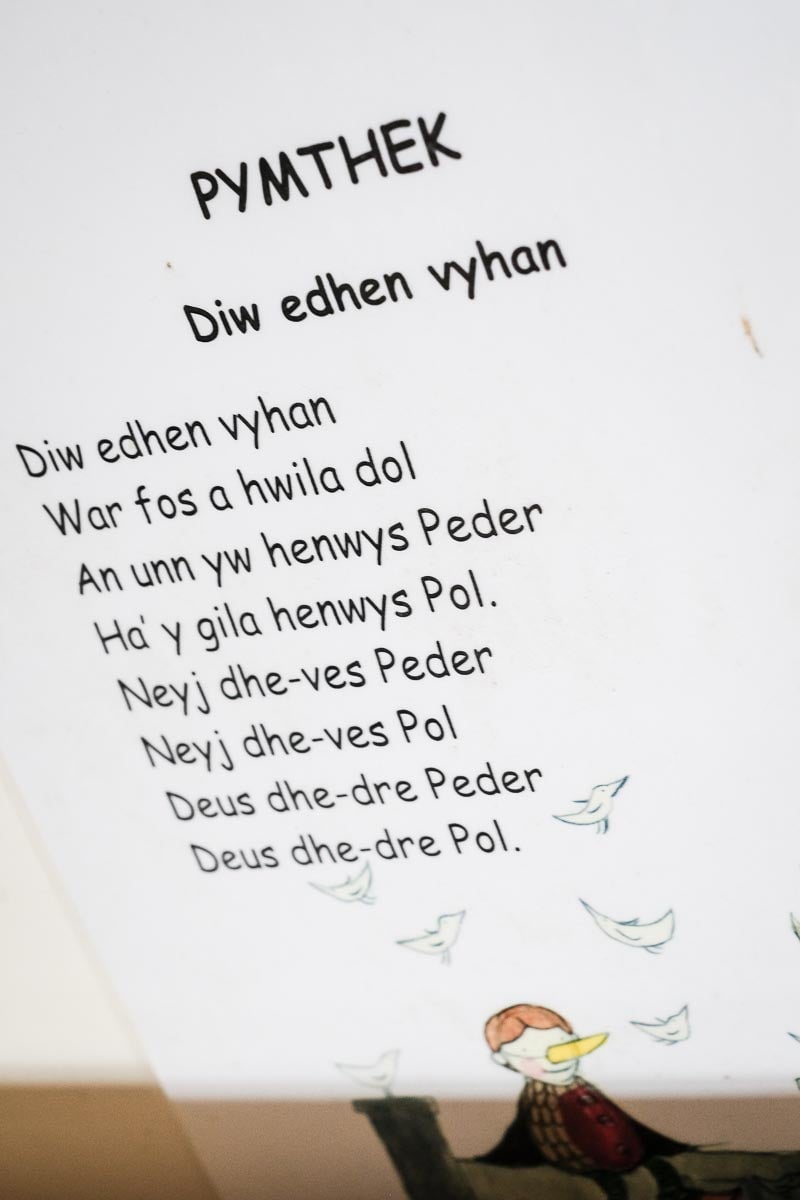

The children understand what Champliaud and Esther Johns, another volunteer, say to them in Cornish. They mostly reply in English (or, in the case of Champliaud’s children, in French), which shows their passive competence to be better than their active usage. The adults’ occasional prompts to speak “yn Kernewek” will often get them to switch tongues. Rituals are important: a game based around a song in Cornish that everyone knows, for example.

But earlier graduates of the creche have gone on to schools where their Cornish, unsupported, tends to wither; some have found themselves chided for using Cornish words. For the language to survive, it needs speakers of all ages. For now it has only small children, a few adults like Gwenno, and a band of mostly older enthusiasts. That’s a lot more than any other language trying to come back from the dead, but Cornish’s isolated speakers need to link up if the language is to truly thrive.

Cornish has the advantage of existing in a rich country that could afford more to support it. But it has the disadvantage of sharing that country with the biggest and most useful language in the world. Many people will pragmatically decide that Cornish is not worth their time and money. As Henry Jenner observed in the 19th century, “The reason why a Cornishman should learn Cornish, the outward and audible sign of his separate nationality, is sentimental, and not in the least practical.” Its resurrection will rest on the strength and breadth of that sentiment. If it cannot spread, Cornish may be trapped in eternal reawakening, not truly asleep, but never making it out from under the covers into the world.

Johns, a grandmother to three of the children at her creche, says her optimism comes and goes. But she reports at least one reason to believe in the future of Cornish. When her daughter, Alice, was complaining about the loss of government funding, Johns’ granddaughter, aged five, chimed in: “We’ll just do it anyway.”