Why we keep coming back for mergers even though they don’t work

The next merger boom is already here.

The next merger boom is already here.

It’s easy to think such a statement is based upon optimism following the worst post-war recession in living memory, new sovereign and municipal debt crises seemingly arising once a month, and the still-unknown consequences of quantitative easing.

But it’s not the case entirely.

New merger booms always have their doubters, and the present cyclical upsurge is no exception. For every few articles such as The Economist’s “Shall We” anticipating a rise in overall merger activity and volume, there seems to be at least one other media piece bemoaning stagnant deal total transaction numbers when assessed on a year-to-year basis.

But understand the factors behind those apparently flat numbers through February through March, and the result is a decidedly more buoyant forward perspective, merger-wise.

Tech sector deal volume has risen fairly consistently since the second half of 2011, particularly in social networking. Bank financing—required fuel for merger-cycle growth once the initial cheap, cash-only opportunities are depleted—has been a question mark for several quarters, as bank capital adequacy levels are debated in New York and Brussels. But merger financing is historically a profit-leader, and the siren-song allure of increased profits is music to embattled bankers’ ears.

The Economist piece points to an additional explanation for the relatively subdued levels of deal volume in this decade’s signature M&A cycle through about February of this year: hesitancy on the part of would-be operating company acquirers to blindly chase those sexy-but-doomed deals, which were reminiscent of merger bubbles past.

No longer are dud deals rubber-stamped by the board just on the say of the acquiring company chief executive.

Those mistakes included “transformational” deals designed to puff up the acquiring firm CEO’s ego and temporary market stature while changing a utility into an entertainment conglomerate (Vivendi/Universal) or a fading dial-up net service provider into a multimodal print-and-virtual media juggernaut (AOL/TimeWarner). Both deals—and transactions resembling them—are today correctly viewed as being merger train wrecks. These errors shortened chief executives’ careers while stalling the acquiring company’s momentum and competitiveness.

The newest merger boom

As spring 2013 officially heats up and becomes summer, the corner in the M&A deal marketplace finally appears to have been turned, with tech leading the way. It all started with Facebook’s shock acquisition of Instagram shortly before its May 2012 Initial Public Offering at DOUBLE the price set a week earlier.

At one point in time, Facebook/Instagram appeared to be a one-off. But social networking competitors, and those trying to make up for lost time, have picked up the momentum, exemplified by Google’s acquisition of Waze and Yahoo’s acquisition of Tumblr (the latter snatched away from Facebook at the eleventh hour). International telecoms, local news media, natural resource companies, utilities and pharma are all now picking up their consolidation pace. Announcements of the creation of acquisition war chests come once-per-week, signaling acquirers on the hunt.

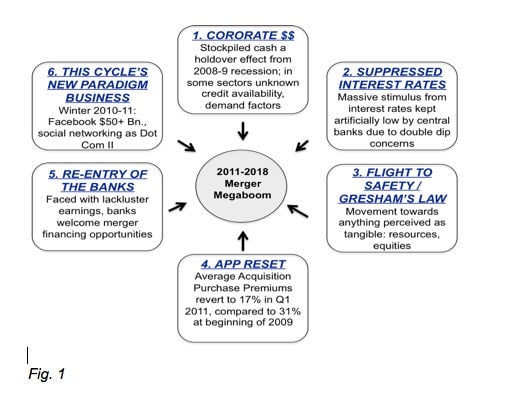

Thus, the customary factors, which have driven each of the past three post-merger booms are now all falling into place (Fig. 1). Plus one more: record high share prices coincide with new expansion optimism.

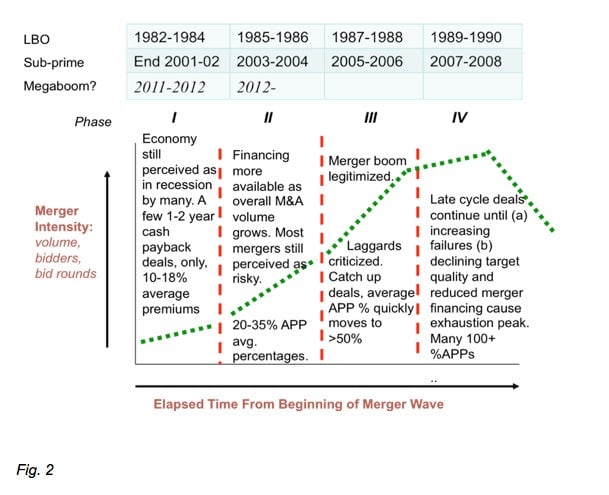

In a phrase, mergers are once again beginning to appear safe to do. The result is that the present merger boom appears to be in second phase of a predictable pattern (Fig. 2). With returns from internal investments now often disappointing to outright career-threatening, it is at this point in time in recoveries past that chief executives begin looking outside the firm: to strategic alliances, new commercial licenses and contracts, and most conspicuously, acquisitions of other companies.

As in any marketplace, the intensity of buying mania matters in M&A. The number and range of quality merger targets for external investment quickly disappear as the merger cycle ages and a ‘buyers’ panic’ takes hold. In the late phases of recent merger cycles past (1982-1990, 1996-2000, 2002-2008) all that’s left to acquire in the final, frantic months of the merger cycle- just before the bubble pops- are poorer quality target companies at prices so high that acquisition regret is almost assured.

Thus, not only do merger cycles matter, but knowledge of them are also critical to the acquiring company’s CEO in order to know which part of the acquisition cycle she or he is entering, thus helping ensure the highest chances for M&A program success.

Yes, Most Mergers Will STILL Fail

Is it really safe to jump into the merger pool? History suggests that the answer is “mostly no” as evidenced by more than 20 articles and papers indicating that two-thirds or more of all deals “fail” based on the criteria those researchers applied.

But can companies do better? With spectacular merger missteps such as BofA/Countywide Financial, Hewlett-Packard/Autonomy and RBS/ABN Amro all in recent memory, every wannabe acquirer gives lip service at least to prudent acquisition practices for the next deal: determining whether the financial return from the deal justifies the outlay (rather than total reliance, nebulous, subjective notions such as “strategic fit”), and assessing whether the acquisition purchase premium (APP)— referring to the amount that has to be paid above the target company’s share price in order to close the deal—is mostly backed by achievable synergies: postmerger improvements.

Whether or not such prudence is real or continues yet to remain. Figure 2 shows how modest merger activity in early phases of M&A cycles past and present quickly become runaway buyers-panic bubbles, especially as late arrivers to the party scramble to make up for lost time.

As the current merger cycle marches through its second phase (of four), merger activity is no longer a matter of business media speculation, but rather, is confirmed by companies own acquisition war chests. In October 2012, 3M closed its biggest deal in two years and in the May 2013 declares that more deals are on the horizon.

This month, following speculation about its pursuit of Spain’s Telefonica, telecommunications giant AT&T openly admits to what the financial market had already suspected for months: earnest pursuit of international deals, especially those involving next generation 4G mobile technology.

Steady, moderate acquirer John Chalmers of Cisco Systems endures as a poster boy for this acquisition boom, in stark contrast in terms of both style and substance to the pop-biz media stars of M&A bubbles past, such as Jean-Marie Messier of Vivendi or Jurgen Schrempf of Daimler-Benz. Firms such as Cisco, 3M, Apple and PepsiCo typify merger prudence for others in the new boom: generally (but not always) smaller-sized deals, closely aligned with areas of existing or emerging strength in those organizations, justified on a hard numbers basis, and acquired at a price likely to be perceived by both the financial markets and their own boards as justifiable.

Merger volume will still increase, even if most mergers continue to disappoint

For argument’s sake, let’s pretend that today, there will be no discernable improvement in overall merger performance in the present-merger wave, compared to the disappointments of last three post-1980 M&A cycles.

Does that mean that the newest merger boom will sputter and crash, as acquirers become timid and/or scared again? Despite the reality that most mergers STILL fail, the answer to that question is “no” (at least over the next few years) for reasons including:

I’m the exception. Wannabe merger dealmakers, consultants and advisors try to turn lemons into lemonade, acknowledging that most mergers disappoint, but that they’re just the guys to help find the one-third of transactions that are viewed as successful nine months after the close.

Looking for alternatives. Holding cash and near-cash means close to zero returns, and even less, if new indications of return of modest inflation persist. The acquiring firm’s easy areas for organic growth, such as product line extension and expansion into contiguous geographic areas, are quickly becoming used up. What’s left? External investment, usually referred to by its other name: mergers.

Spending imagined wealth. Never mind that in broad-based stock market booms such as the rally since late 2010, prices of ALL companies tend to rise, acquirer and target alike. The corporate fiction—and the sense on the board—persists that “we should do something to take advantage of our high stock price.” A likely target? Another company.

Acquiring company CEO hubris. Presiding over a major acquisition during his or her period as company CEO remains as a driving force, admitted or not. Faced with a reality that only around a third of deals succeed, the super-confident new chief executive has little doubt of his/her own ability to beat the odds.