How we’ll know when China really is working with the US on North Korea

This past weekend Donald Trump praised his Chinese counterpart for his efforts to address the increasingly tense situation on the Korean peninsula. The US president said Xi Jinping “is working to try and resolve a very big problem, for China also.”

This past weekend Donald Trump praised his Chinese counterpart for his efforts to address the increasingly tense situation on the Korean peninsula. The US president said Xi Jinping “is working to try and resolve a very big problem, for China also.”

That problem, of course, is the ongoing development of ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons by North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un, despite UN sanctions. Kim seems hellbent on being able to hit North America with nuclear-tipped missiles, and some analysts think he’s only a few years away from it.

Trump suggested he might be willing to meet Kim under the right conditions, echoing sentiments from secretary of state Rex Tillerson that the US is open to direct talks with North Korea as long as the agenda is a “denuclearized Korean peninsula.”

Fear of military force is unlikely to bring North Korea to the table, if the past half century or so is anything to go by. But the Trump administration is hoping that the threat of crushing sanctions against North Korea—with strong assistance from China—might do the trick.

Pressure, but not too much

There is an argument to be made that sanctions have never been properly used against North Korea, and evidence to suggest that the nation’s elite will feel the consequences if they are—perhaps enough to bring about change.

But China, as North Korea’s largest trading partner, must play a stronger role, and it’s unclear how much pressure China is willing to apply—despite the “great chemistry” Trump says he’s developed with Xi.

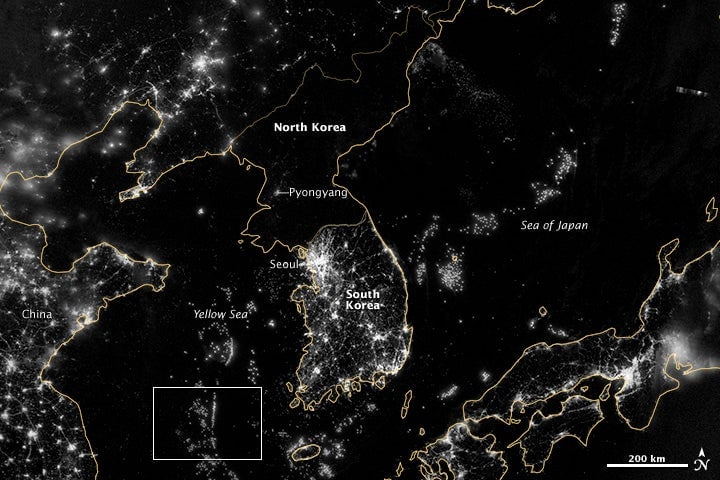

Beijing, like Washington, doesn’t want to see its unpredictable neighbor armed to the teeth with nuclear-tipped missiles. But Beijing also wants to avoid a government collapse in North Korea, or applying so much pressure that Kim becomes nervous enough to start a conflict. Either scenario could result in millions of impoverished North Koreans streaming across the border into China.

“They want to put pressure on him,” says Carla Park Freeman, director of the Foreign Policy Institute at the School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, DC. “They have implemented sanctions, but they’ve implemented them in a way that still allows the North Korean regime to sustain itself.”

China reported last month that its trade with North Korea actually expanded in the first quarter (paywall), despite complying, it says, with UN sanctions regarding coal. It was up 37.4% from the same period a year ago.

Which raises the question: How will we know if Beijing is applying sufficient pressure to bring about change, and not just paying lip service?

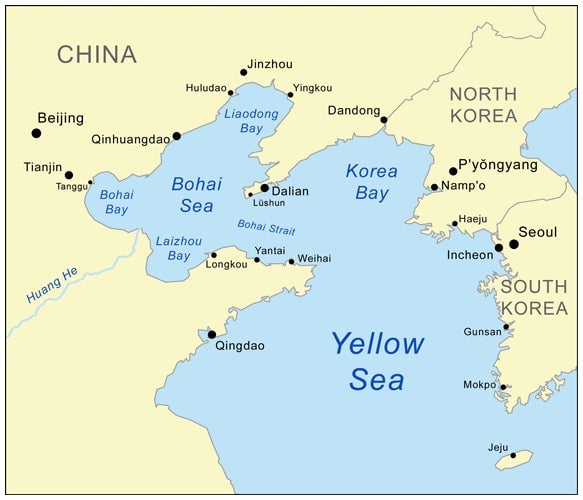

The busy Yellow Sea

One indication would be trade traffic patterns. China accounts for about 90% of North Korea’s trade. ”In terms of cross-border trade, we can observe activity at the major crossing points,” says Paul Stares, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “We can try to gauge the availability of certain goods in stores.”

North Korea has mineral reserves (including rare-earth minerals) valued at more than $6 trillion—and China isn’t shy about importing its share (paywall). The UN sanctions prohibit trading in minerals with North Korea, in some cases partially, in others completely, depending on the mineral.

“A reduction in the volume of coastal freighters plying the Yellow Sea and trucks crossing the Yalu River would signal a tangible Chinese effort to apply pressure to Kim Jong-un,” says Sean Liedman, an adjunct fellow at the Center for New American Security, referring to the river that divides the two nations along much of their shared border and the sea that lies between the Korean peninsula and China.

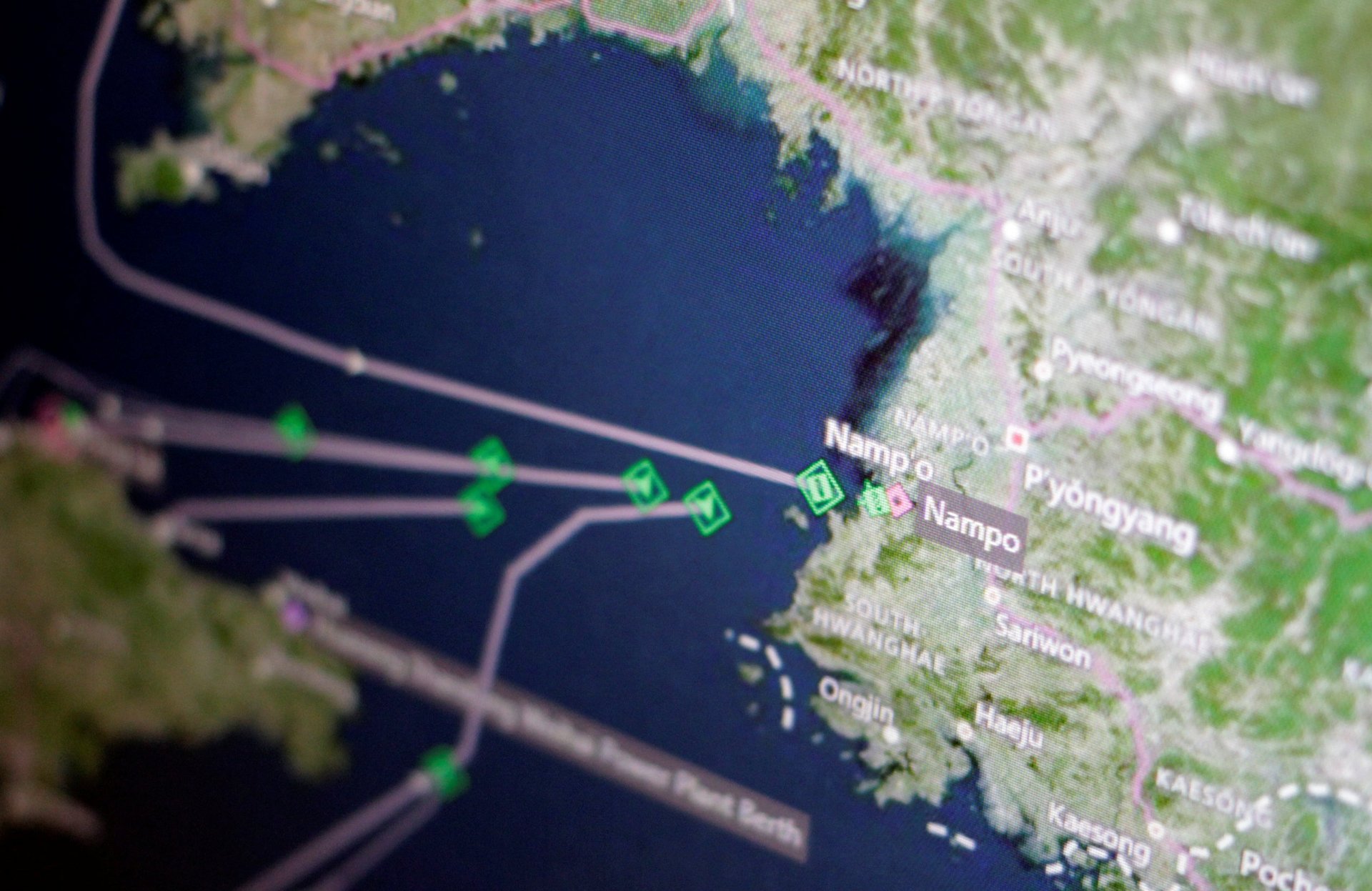

An example came when when China turned back cargo ships from the port of Nampo, North Korea last month. The ships were carrying coal, sales of which are an important source of funds for Pyongyang. Trump heaped praise on Xi, who had just visited him in Florida, for the action. “Nobody has ever seen such a positive response on our behalf from China,” Trump said on April 17.

The importance of the limited flow of luxury goods like liquor and flat-screen TVs into North Korea should not be underestimated either, says Robert Kelly, an associate professor of international relations at Pusan National University in South Korea.

“When I went to North Korea, you could see guys walk straight from Chinese duty-free in the Beijing Capital International Airport onto Air Koryo. Air Koryo lands in Pyongyang about two hours later. Where do you think that alcohol is going? It’s not going to the farmers, it’s going straight to Pyongyang.”

Fewer fine things reaching the upper crust could contribute to a power shift.

“If hard currency and luxury goods were cut off, the regime could lose the support of the elite,” says David Maxwell, associate director of the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University.

Evidence of pressure from Beijing would also be seen in the prices of consumer goods. “I think what we would see is sustained high prices and shortages for both goods and restricted supplies of oil” says Freeman.

Hitting North Korea where it hurts

Oil fuels the military, Freeman notes, so energy restrictions would be especially effective in hurting the Kim regime. China is believed to supply North Korea with most of its oil. Official numbers haven’t been released in a few years, but estimates put the annual volume of crude oil imports from China to North Korea at 520,000 metric tons (about 573,200 tons). South Korea imported more than 12.6 million metric tons of crude in March.

The Global Times, a state-backed Chinese tabloid, recently suggested a sixth nuclear test by the North would merit China cutting oil shipments. Doing so would be devastating to North Korea’s economy.

China could also apply major pressure by curtailing access to its financial system. Kelly points to 2005 US sanctions against (paywall) Banco Delta Asia, a bank in Macau holding North Korean funds, as an example: “The North Koreans got really hyper-sensitive about that, and there was a lot of regime activity about that the intelligence community picked up.”

But, he adds, some of the Chinese elite might also be nervous about actions taken against Chinese banks. “You hear people saying, ‘Hit them [the North Korean elite] where it hurts: Go after their cash in Chinese banks.’ The problem is, a lot of people are worried that’s tied to Chinese-elite money itself, and then you’re chewing towards the middle, as it were.”

“There is I think resistance to sort of showing the books because of other activities those banks may be used for for other actors within the Chinese system,” adds Stares.

Out of Beijing’s control

These days, much of the North Korean economy is fueled by the black market. Though Chinese players are heavily involved, it isn’t necessarily under Beijing’s control.

“Even if Beijing went ‘all in’ on economic sanctions and embargoes, the Chinese Communist Party may find it difficult to curtail black-market smuggling activities between Chinese companies and the DPRK,” says Liedman.

“I think North Korea has developed a whole black-market economy that helps keep it going,” says Freeman. “Not necessarily feeding lots of people, but it keeps the government going, and it probably helps pay for the nuclear program.”

North Korea has economic relationships outside of China, of course. For instance the regime essentially rents out slave labor to other repressive governments. It’s also a weapons supplier, and it profits handsomely from the civil war in Syria, helping the military of president Bashar al-Assad with parts, artillery, and technical assistance. It’s a partner with Iran on various fronts, including, possibly, nuclear weapons development.

It also dabbles in cyber-theft and has its own illicit drugs industry.

History lessons

Many take it for granted that there’s some amount of economic pressure China could apply that would make the Kim regime give up its nuclear weapons. But ”this is a widespread assumption that probably has no basis in fact,” notes John Pike, a military analyst at Globalsecurity.org. “Kim Jong-un saw what happened to Saddam [Hussein] and [Muammar] Gaddafi, and he doesn’t want to wind up in a necktie party.”

“Nuclear weapons are also a key tool as part of its blackmail diplomacy,” notes Maxwell. “The threat of use, proliferation, as well as holding out the possibility of talks, provides the regime with leverage to use with the US and international community.”

The Kim regime “has no intention of negotiating away its nuclear-weapons program,” he adds, though it may be open to “limitation and reduction talks.”

Then again, the elites surrounding Kim might apply pressure if their status and way of life is threatened. As a North Korean official said (paywall) after the US hit Banco Delta Asia, “You finally found a way to hurt us.”

China, Pyongyang knows, could also bring the pain.