Microsoft’s new head of research has spent his career building powerful AI—and making sure it’s safe

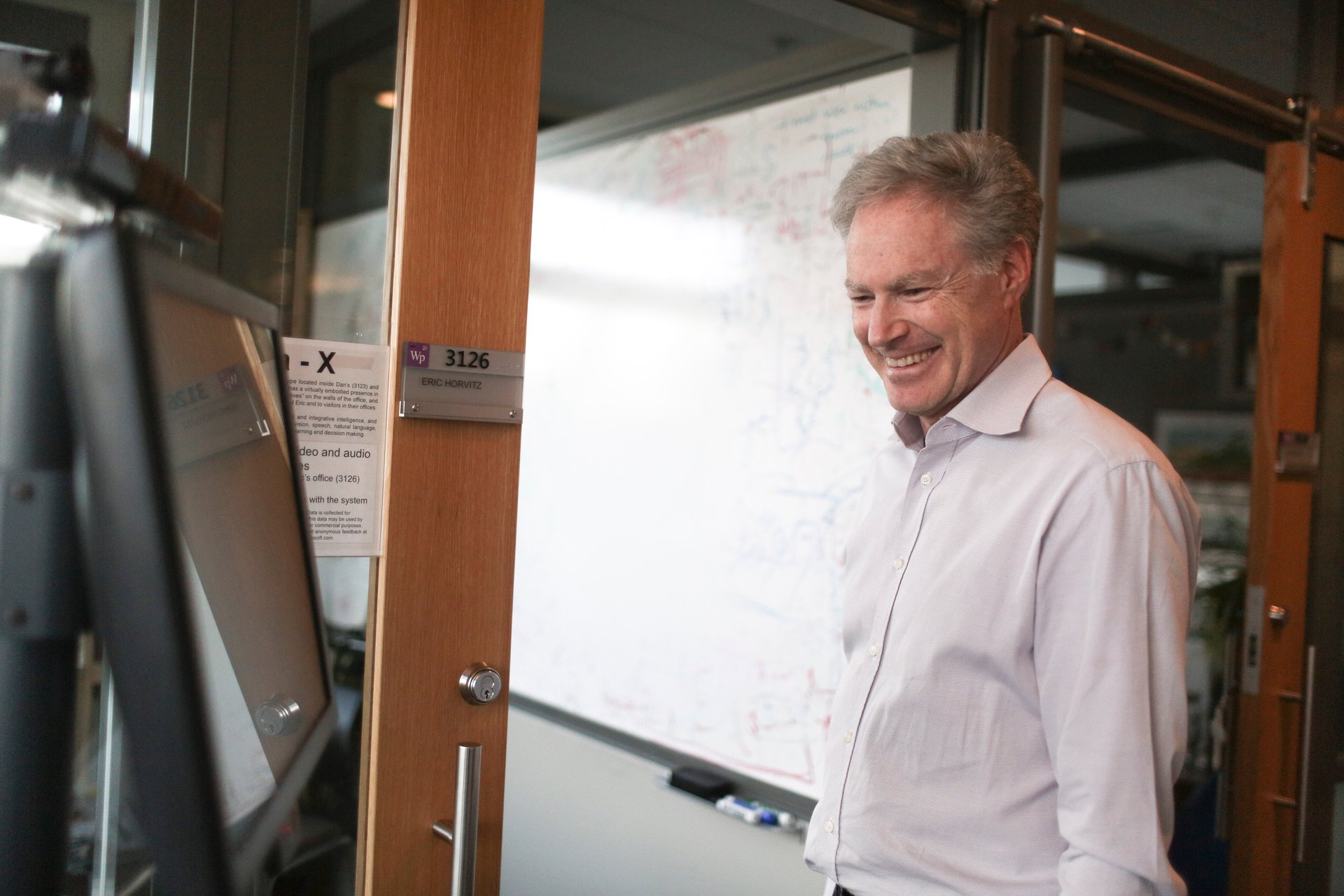

As director of Microsoft’s Building 99 research lab in Redmond, Washington, Eric Horvitz gave each of his employees a copy of David McCullough’s The Wright Brothers. “I said to them, ‘Please read every word of this book,’” Horvitz says, tapping the table to highlight each syllable.

As director of Microsoft’s Building 99 research lab in Redmond, Washington, Eric Horvitz gave each of his employees a copy of David McCullough’s The Wright Brothers. “I said to them, ‘Please read every word of this book,’” Horvitz says, tapping the table to highlight each syllable.

Horvitz wanted them to read the story of the Wright brothers’ determination to show them what it takes to invent an entirely new industry. In some ways, his own career in artificial intelligence has followed a similar trajectory. For nearly 25 years, Horvitz has endeavored to make machines as capable as humans.

The effort has required breaking new ground in different scientific disciplines and maintaining a belief in human ingenuity when skeptics saw only a pipe dream. The first flying machines were “canvas flapping on a beach, it was a marvel they got it off the ground,” says Horvitz. “But in 50 summers, you’ve got a Boeing 707, complete with a flight industry.”

Horvitz wants to fundamentally change the way humans interact with machines, whether that’s building a new way for AI to fly a coworker’s plane or designing a virtual personal assistant that lives outside his office. He will get a chance to further his influence, with his appointment yesterday as head of all of Microsoft’s research centers outside Asia.

In his new role, Horvitz will harness AI expertise from each lab—in Redmond, Washington; Bangalore, India; New York City, New York; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Cambridge, England—into core Microsoft products, as well as setting up a dedicated AI initiative within Redmond. He also plans to make Microsoft Research a place that studies the societal and social influences of AI. The work he plans to do, he says, will be “game-changing.”

Horvitz, 59, has the backing of one of the industry’s most influential figures. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has spent the last two years rebuilding the company around artificial intelligence. “We want to bring intelligence to everything, to everywhere, and for everyone,” he told developers last year.

Handing Horvitz the reins to Microsoft’s research ensures a renewed, long-term focus on the technology.

Difficult questions about AI

Horvitz, long a leading voice in AI safety and ethics, has used his already considerable influence to ask many of the uncomfortable questions that AI research has raised. What if, for instance, the machines unconsciously incarcerated innocent people, or could be used to create vast economic disparity with little regard to society?

Horvitz has been instrumental in corralling thinking on these issues from some of tech’s largest and most powerful companies through the Partnership on Artificial Intelligence, a consortium that is eager to set industry standards for transparency, accountability, and safety for AI products. And he’s testified before the US Senate, giving level-headed insight on the promise of automated decision-making, while recommending caution given its latent dangers.

In 2007, Horvitz was elected to a two-year term as president of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), the largest trade organization for AI research. It’s hard to overstate the group’s influence. Find an AI PhD student and ask them who’s the most important AI researcher of all time. Marvin Minsky? President from 1981-1982. John McCarthy? President from 1983-1983. Allen Newell? The group’s first president, from 1979-1980. You get the picture.

Throughout Horvitz’s AAAI tenure, he looked for the blind spots intelligent machines encountered when put into the open world. “They have to grapple with this idea of unknown unknowns,” he says. Today, we have a much better idea of what these unknowns can be. Even unintentionally biased data powering AI used by law enforcement can discriminate against people by gender or skin color; driverless cars could miss seeing dangers in the world; malicious hackers could try to fool AI into seeing things that aren’t there.

The culmination of Horvitz’s AAAI presidency, in 2009, was a conference held at the famous Asilomar hotel in Pacific Grove, California, to discuss AI ethics, in the spirit of the meetings on DNA modification held at the same location in 1975. It was the first time such a discussion had been held outside academia, and was in many ways a turning point for the industry.

“All the people there who were at the meeting went on to be major players in the implementation of AI technology,” says Bart Selman, who co-chaired the conference with Horvitz. “The meeting went on to get others to think about the consequences and how to do responsible AI. It led to this new field called AI safety.”

Since then, the role of AI has become a topic of public concern. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg has had to answer the very question that Horvitz began a decade ago: Who’s responsible when an algorithm provides false information, or traps people within a filter bubble? Automakers in Detroit and their upstart competitors in Silicon Valley have philosophers debating questions like: When faced with fatalities of passengers or pedestrians, who should a driverless car decide to kill?

An obsessive mind

But there are also unquestionably good uses for AI, and Horvitz arguably spends more time thinking about those—even when he’s far from the lab.

When I first met Horvitz, he was stepping off the ice at the Kent Valley Ice Centre hockey rink in, about a 30-minute drive south of Building 99. Fresh from an easy 4-1 victory on the ice and wearing a jersey emblazoned with the team name “Hackers,” he quickly introduced me to teammate Dae Lee, and launched into a discussion of a potential uses for AI. “There are 40,000 people who die every year in the hospital from preventable errors,” Horvitz said, still out of breath and wearing a helmet. “Dae is working with some predictive machine-learning algorithms to reduce those deaths.”

Meeting with him the next day, examples abounded: Algorithms that can reduce traffic by optimizing ride-sharing, systems that aim to catch cancer a full stage before doctors based on your search history (the idea being that you might be searching for information about health conditions that indicate early warnings of the disease), and trying to predict the future by using the past.

Horvitz has been chewing on some of these ideas for decades, and he’s quick to tell you if a thought isn’t yet completely formed—whether he’s discussing the structure of an organization he’s a member of, or a theory on whether consciousness is more than a sum of its parts (his current feeling: probably not).

In college, Horvitz pursued similar questions, while earning an undergraduate degree in biophysics from Binghamton University in upstate New York. After finishing his degree, he spent a summer at Mt. Sinai hospital in Manhattan, measuring the electric actuation of neurons in a mouse brain. Using an oscilloscope, he could watch the electric signals that indicated neurons firing.

He didn’t intend to go into computer software, but during his first year of medical school at Stanford, he realized he wanted to explore electronic brains—that is, machines that could be made to think like humans. He had been looking at an Apple IIe computer, and realized he had been approaching the problem of human brain activity the wrong way.

“I was thinking about this work of sticking glass electrodes to watch neurons would be like sticking a wire into one of those black motherboard squares and trying to infer the operating system,” he said.

He was trying to understand organic brains from the outside in, instead of building them from the inside out. After finishing his medical degree, he went on to get a PhD in artificial intelligence at Stanford.

Some of his first ideas for AI had to do directly with medicine. Among those formative systems was a program meant to help trauma surgeons triage tasks in emergency situations by enabling them to quickly discern whether a patient was in respiratory distress or respiratory failure.

But the machines at the time, like the famed Apple IIe, were slow and clunky. They “huffed and puffed” when making a decision, Horvitz says. The only way for a machine to be able to make a good decision within the allotted time was if the machine knew its limitations—to know and decide whether it could make a decision, or whether it was too late. The machine had to be self-aware.

Science fiction

Self-aware machines have been the fodder for science fiction for decades; Horvitz has long been focused on actually constructing them. Since the rise of companies like Amazon, Google, and Facebook—which use AI to manage workflow in fulfillment centers or in products like Alexa or search, or to help connect people on social media—much research has been focused on building deep neural networks, which have been proven useful for recognizing people or objects in images, recognizing speech, and understanding text. Horvitz’s work pinpoints the act of making a decision: How can machines make decisions like expert humans, considering the effects on themselves and the environment, but with the speed and improvable accuracy of a computer?

In his 1990 Stanford thesis, Horvitz described the idea as “a model of rational action for automated reasoning systems that makes use of flexible approximation methods and decision-theoretic procedures to determine how best to solve a problem under bounded computational resources.”

We’ll just call it a kind of self-awareness. While the term is often used interchangeably with “consciousness,” a term that philosophers still argue over, self-awareness can be considered acting after understanding one’s limitations. Horvitz makes it clear that self-awareness isn’t a light switch—it’s not just on or off, but rather a sea of small predictions that humans make unconsciously every day, and that can sometimes be reverse-engineered.

To see this in action, consider a game that Horvitz worked on in 2009, where an AI agent moderated a trivia game between two people. It would calculate how much time it had to formulate a sentence and speak it, predicting whether it would be socially acceptable to do so. It was a polite bot. In addition, if a third person was seen by the AI’s camera in the background, it would stop the game and ask if they wanted to join—a small feat for a human, but something completely out of left field for an artificial game show host.

”And that’s the magic, right? That’s the moment where it goes from just being a system to being alive,” says Anne Loomis Thompson, a senior research engineer at Microsoft. “When these systems really work, it is magic. It feels like they’re really interacting with you, like some sentient creature.”

Outside of Microsoft, Horvitz’s interests in AI safety have gone well past the Asilomar conference. He’s personally funded the Stanford 100 Year Study, a look at the long-term effects of artificial intelligence by a cadre of academics with expertise in economics, urban development, entertainment, public safety, employment, and transportation. Its first goal: to gauge the impact of artificial intelligence on a city in the year 2030.

The Partnership on AI, made up of AI leaders from Microsoft, Google, IBM, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple, represents a way for Horvitz to bring the industry together to talk about use of AI for humanity’s benefit. The group has recently published its goals, chiefly creating best practices around fairness, inclusivity, transparency, security, privacy, ethics, and safety of AI systems. It has brought in advisors from outside technology, such as Carol Rose from the ACLU’s Massachusetts chapter, and Jason Furman, who was US president Barack Obama’s chief economic adviser. Horvitz says there are about 60 companies now trying to join.

Despite the potential dangers of an AI-powered world, Horvitz fundamentally believes in the technology’s ability to make human life more meaningful. And now he’ll have an even larger platform from which to share the message.