Trump has decided not to spend on the one thing that could really deter illegal immigration

The $1 trillion spending bill that the US Congress passed yesterday funnels nearly $1.5 billion extra towards finding and catching undocumented immigrants. But once those migrants are caught, they run into a bottleneck—the courts that decide whether to deport them, which have a case backlog of nearly two years. And the spending bill includes only a modest increase for those courts.

The $1 trillion spending bill that the US Congress passed yesterday funnels nearly $1.5 billion extra towards finding and catching undocumented immigrants. But once those migrants are caught, they run into a bottleneck—the courts that decide whether to deport them, which have a case backlog of nearly two years. And the spending bill includes only a modest increase for those courts.

That means the backlog is likely to persist or even grow, and so will the inevitable use of “catch-and-release,” the practice of letting immigrants go free while they await a court hearing.

That wait has proved to be a big draw for immigrants. Many who don’t have a solid case to stay in the US still risk their lives and thousands of dollars in smuggling fees to cross the border because they know that getting a judge to officially kick them out will take years.

Speeding up judges’ rulings—and promptly removing those who get a deportation order—would drastically change the economics of that decision and make people think twice before leaving their countries, says Gil Kerlikowske, who was US Customs and Border Protection commissioner under the Obama administration. “It sends a pretty powerful message and frankly has a chilling effect on people,” he added during a panel yesterday organized by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, DC-based think tank.

Congress’s spending bill calls for 10 additional judges, but a look at the math suggests a lot more are needed. The budgets for the agencies that intercept and arrest undocumented immigrants—Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—dwarf the money assigned to the agency that processes detainees’ cases, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). Their budget increases were bigger too. CBP’s budget grew by 8% from 2016 to 2017 (though most of that is a one-off provision); ICE’s grew by 9.4%; and EOIR’s by only 4.7%.

During the first two months of the Trump administration, authorities caught some 40,000 immigrants at the border and arrested another 21,000 in the interior of the country. Not all of them are eligible for a court hearing, but many are.

Although the spending bill provides far less extra funding for Homeland Security than president Donald Trump requested—he wanted to add a whopping 15,000 new border patrol and ICE agents—it provides enough for 100 extra officers involved in the job of catching people. That means hundreds of extra cases will likely head to immigration court, even though the rate of border apprehensions has already fallen sharply under Trump. As of March, cases had been sitting there for an average of 669 days, up from 413 days a decade ago, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, or TRAC, which gathers such data.

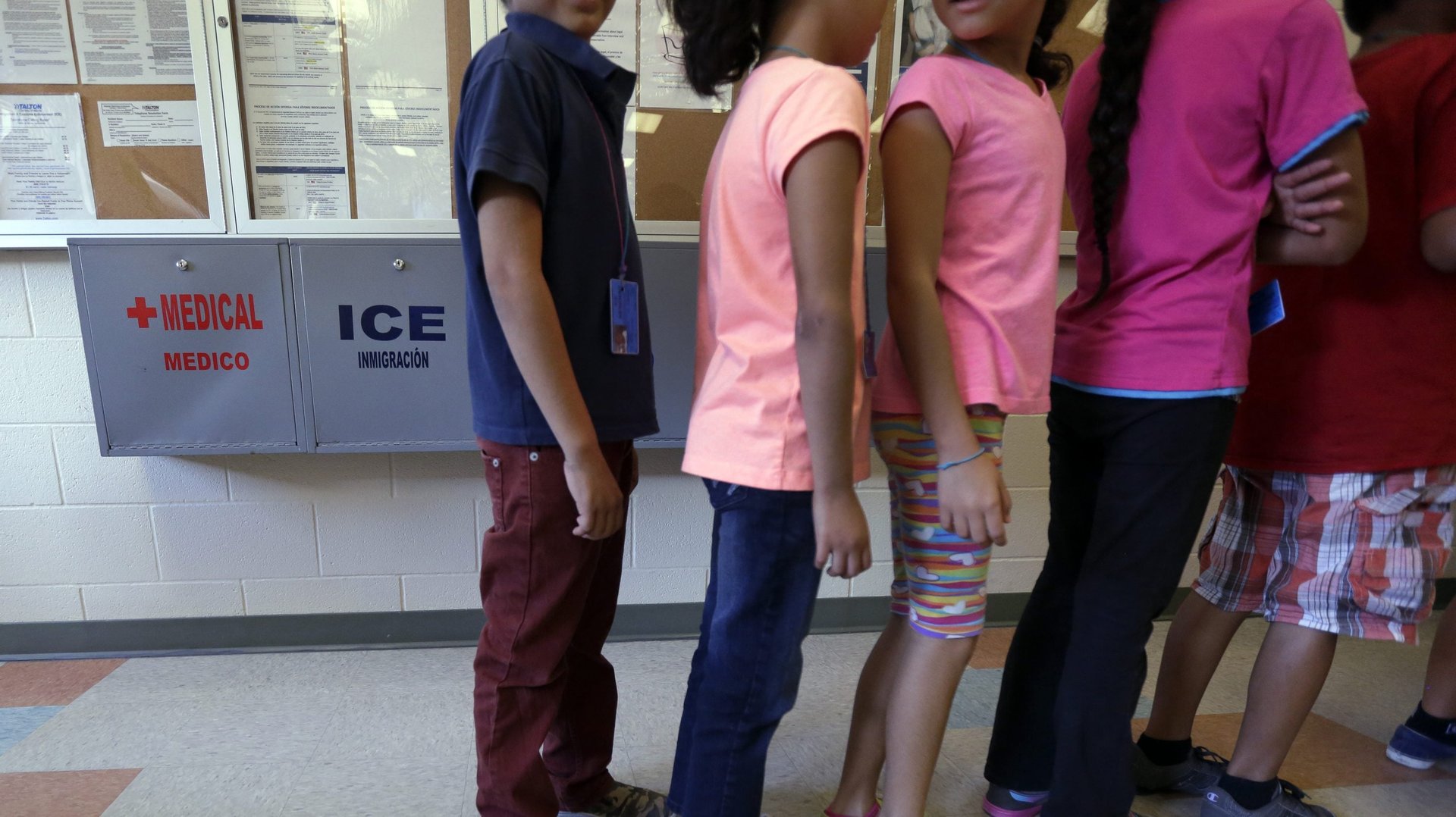

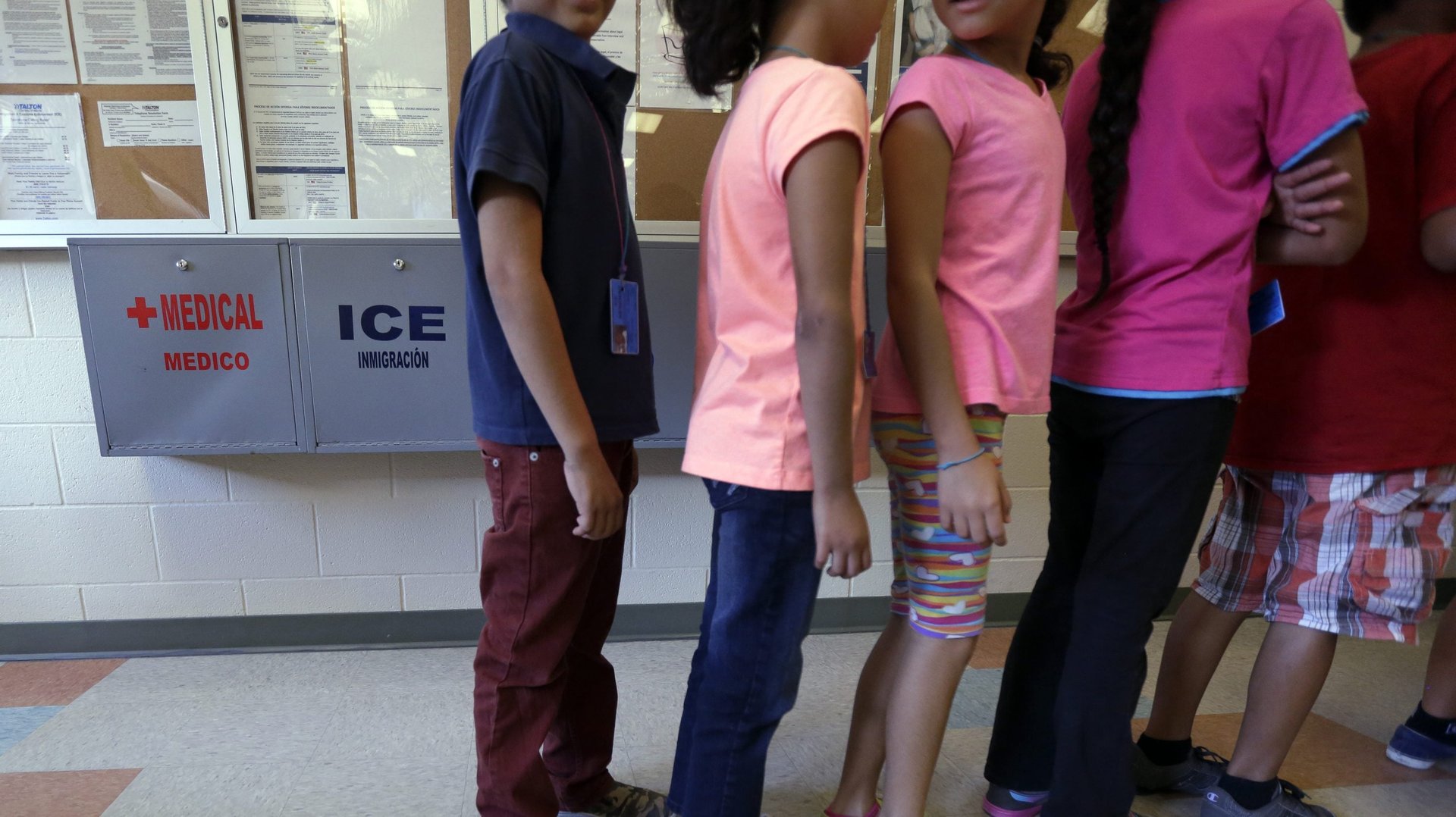

During that time, the government has to either house and feed immigrants or release them. The spending bill tries to address that, setting aside money for nearly 40,000 beds at detention centers. But if 61,000 people were caught in two months, and the wait for a court date is two years… Well, you do the math.

The EOIR budget seems similarly insufficient for the workload. There are roughly 570,000 cases pending in court, according to TRAC. EOIR currently has funding for 374 judges, though only 311 of those positions have been filled. Each judge can process about 750 cases a year. Even with the 10 additional judges under the spending bill—and assuming those and all the other vacant judgeships could be filled and trained up immediately, which they won’t be—it would still take nearly two years to get through the current backlog. By which time even more cases will be waiting.

Based on those numbers, it would make more sense to spend the money destined for enforcement agents on hiring judges instead. If migrants knew they wouldn’t get to stay in the country very long after being caught, a lot fewer of them might make the trip.