Internet car start-ups look to the new mayor of Los Angeles for a helping hand

Anyone keeping up with the battles between online car services and local taxi companies is familiar with this dynamic: Municipal regulators and cab services will use any legal outlet they can to bar new companies leveraging mobile networks from entering the marketplace.

Anyone keeping up with the battles between online car services and local taxi companies is familiar with this dynamic: Municipal regulators and cab services will use any legal outlet they can to bar new companies leveraging mobile networks from entering the marketplace.

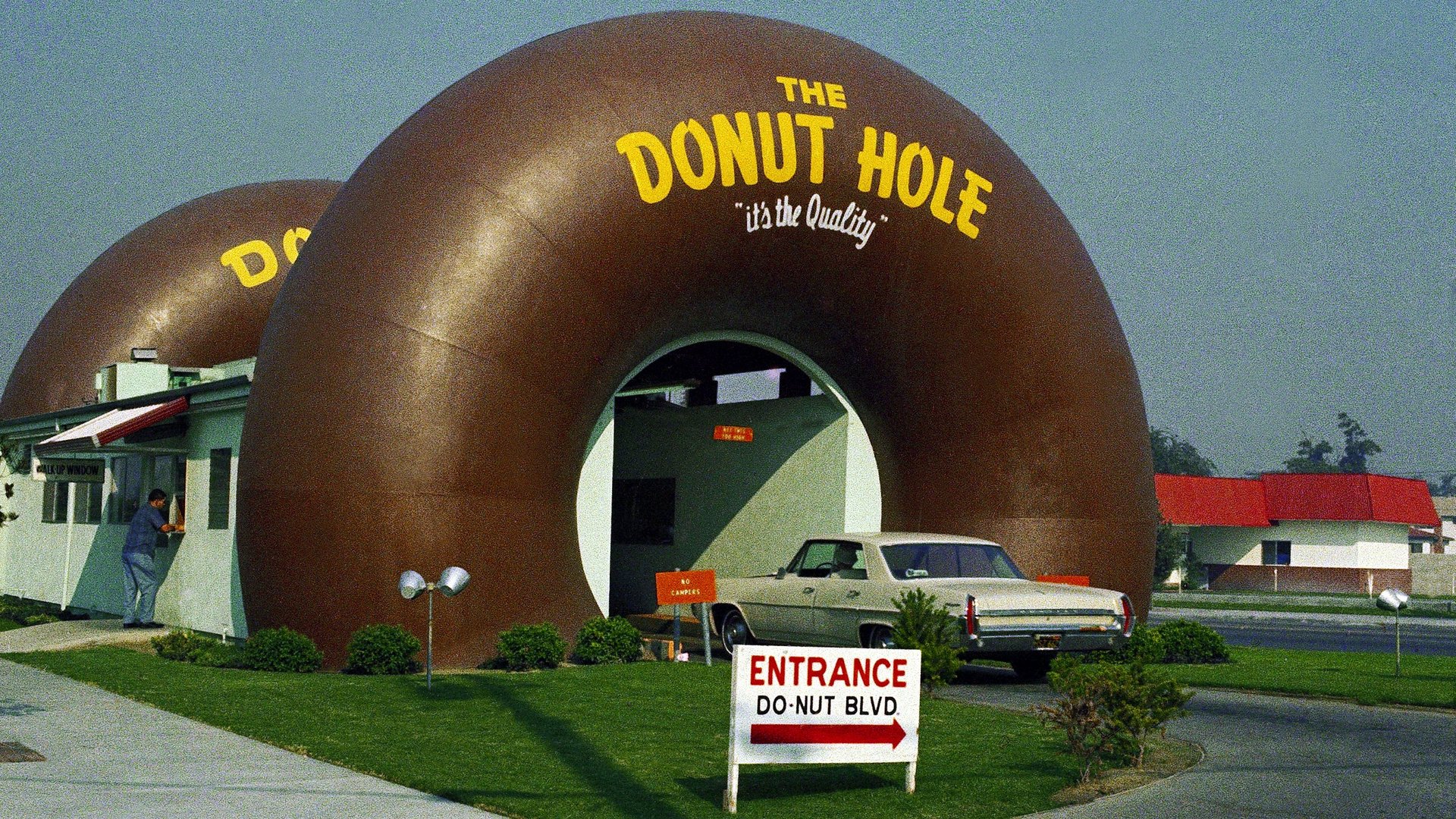

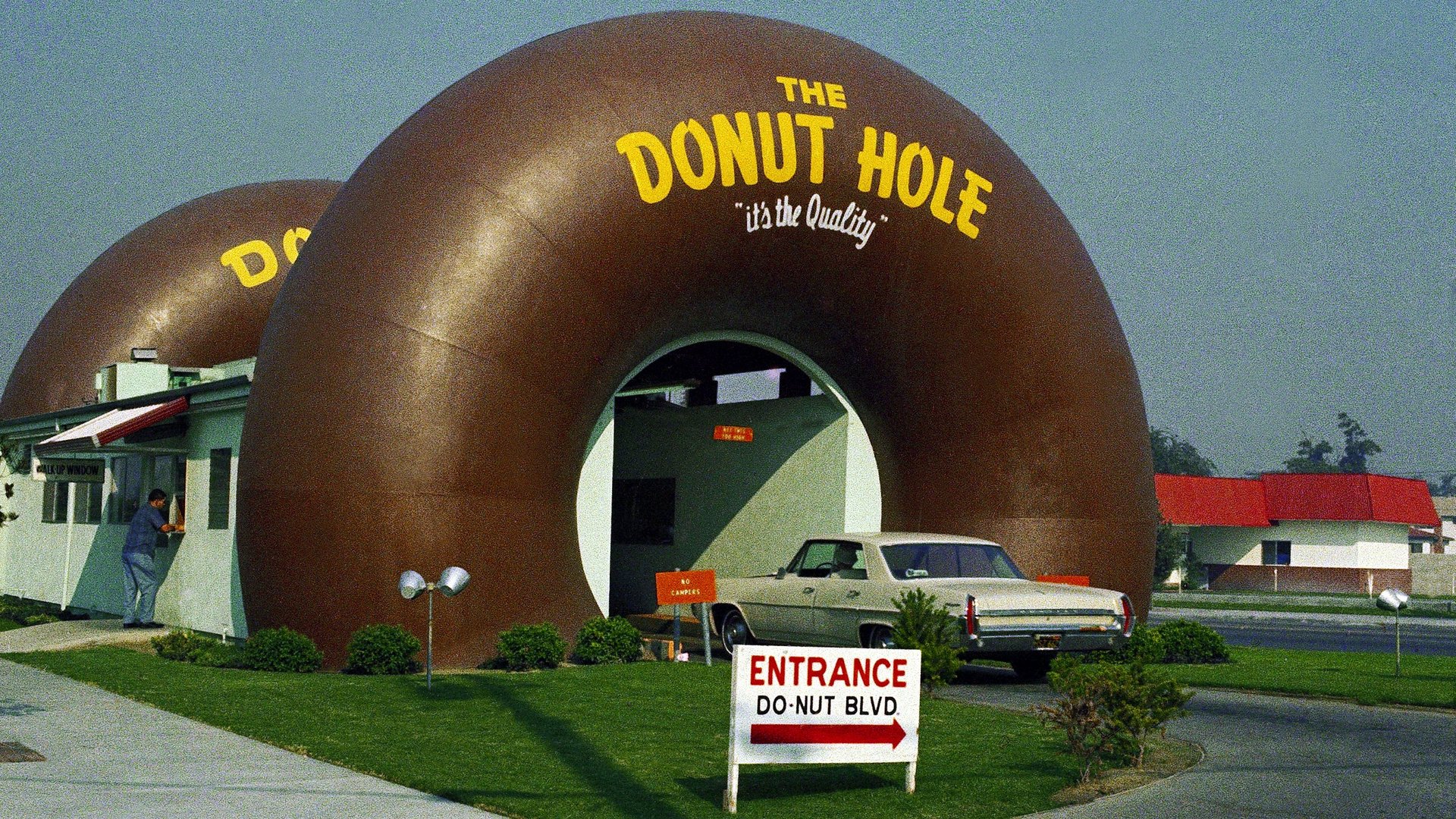

The latest example is in Los Angeles, a city designed around automotive travel, which has been sparring with auto entrepreneurs practically since the technology was invented. LA’s transit agency sent cease and desist letters to Uber, the online car service, as well as Lyft and Sidecar, two community companies that connect car owners with people looking for a ride. All of the services are unwelcome competition for LA cab companies. They’re also all based in San Francisco, LA’s bête noire, the place that usurped LA’s “city of the future” crown.

The tiff partly comes down to jurisdiction. The three companies have compliance agreements with the state of California Public Utilities Commission, which supervises limousines and charter buses. Uber, which often attracts drivers from limousine services, says that because LA explicitly recognizes this state-level authority, its compliance agreements should apply in LA. Uber plans to ignore the cease and desist notice and continue providing service. Lyft said in a statement that it reached out to the LA mayor’s office to attempt to address the city’s concerns.

Taxi cabs started the day circling city hall and honking before voicing their concerns at a new conference, while supporters of the start-ups are making their voices heard through an online petition.

One complaint from cabbies is that the new entrants are unsafe, since they don’t follow city regulations. But the companies say that, as part of their agreement to be regulated by the state, they perform background checks on drivers, provide insurance and certify car safety. Perhaps more convincing is the cabbies’ larger argument that there isn’t really a functional difference between Uber or Lyft and a conventional cab service, despite the legal technicalities.

The real problem is that in Los Angeles, cabs are officially provided by a cartel of nine companies, and the supply of cabs is limited by the city, which drives up the cost of taking a cab. Cab companies also haven’t taken as much advantage of mobile internet to improve customer service. The safety of drivers and passengers in any hired car is important, but it’s unclear what public benefit is derived from regulations that limit their number.

Los Angeles’ newly elected Mayor, Eric Garcetti, takes office on July, 1, and is favored by the burgeoning tech community in LA’s Silicon Beach. Techies are hoping Garcetti will push for some kind of reconciliation between the regulatory system, the existing industry and the new entrants. Uber, despite its rocky past in cooperating with local governments, has found ways to work with cab companies on e-hailing. If Los Angeles can find an amicable compromise, it might once again take the lead in defining American car culture.