A simple change could ensure garment workers a living wage at minimal cost to shoppers

Here’s a novel idea: What if giant fashion brands didn’t derive a profit from pay increases for the underpaid workers making their clothes that are meant purely to bring their incomes up to a living wage?

Here’s a novel idea: What if giant fashion brands didn’t derive a profit from pay increases for the underpaid workers making their clothes that are meant purely to bring their incomes up to a living wage?

That radical notion appears in a new joint report by the Boston Consulting Group and Global Fashion Agenda, a fashion body focused on sustainability, that offers a comprehensive look at the industry’s performance on social and environmental issues. It concludes that a number of changes are necessary to safeguard the wellbeing of those in fashion’s vast supply chain as well as the long-term health of the industry itself. Many of these changes require rethinking basic assumptions underlying the way most brands operate, among them the typical markup structure that determines how worker wages get translated into a share of a garment’s final price tag.

At present, brands bundle labor costs together with all the other expenses involved in producing a garment. To that total amount, they apply their markup, which covers their costs and adds in a profit, to arrive at the sales price of their products. Any increase in labor costs gets multiplied, which can raise the final price of a garment significantly.

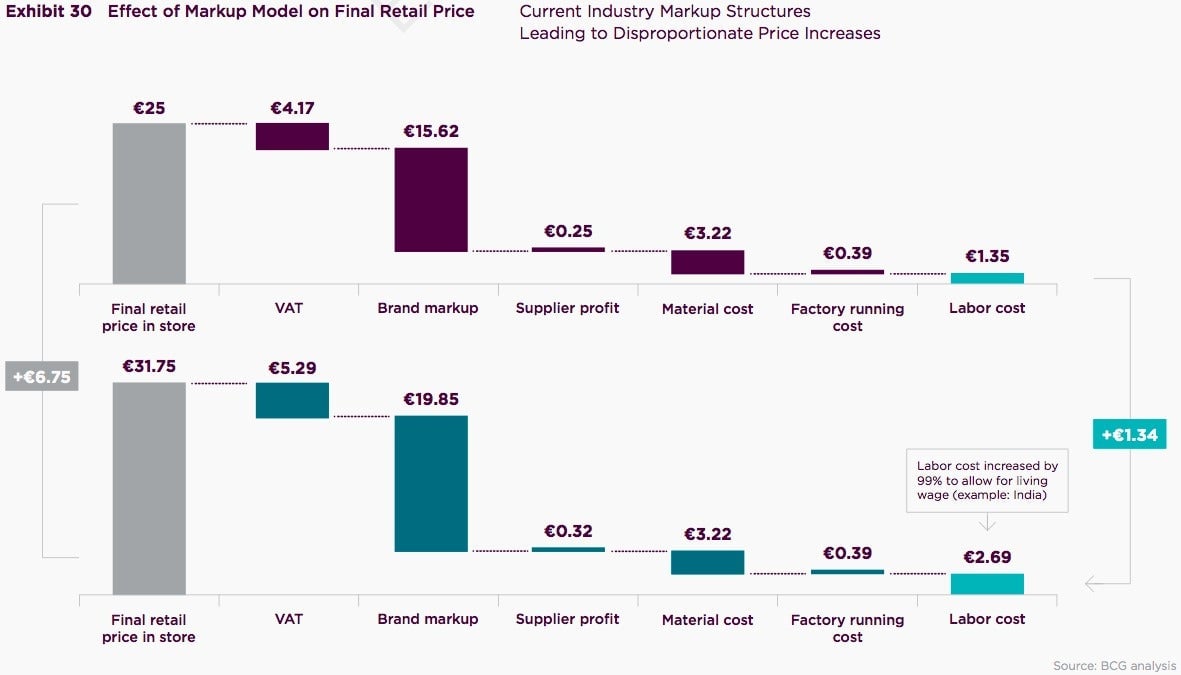

The report offers the example of a t-shirt produced in India, and shows how the final price tag changes if current wages—based on the country’s legal minimum—increase to the amount experts consider (pdf) to be a living wage, meaning one that meets the basic needs of a worker and his or her family. In this case, doubling the wage adds just €1.34 ($1.46) to the labor cost per t-shirt, but raises the store price of the shirt by €6.75. (VAT in the chart below is Europe’s value-added tax.)

It’s not a huge amount, and it’s reasonable to ask why brands wouldn’t just eat the price increase themselves, or why shoppers wouldn’t just pay slightly more to provide better lives for the people making their clothes. But brands are businesses, and particularly for businesses selling cheap fashion to increasingly price-sensitive shoppers, any price jump can have a real impact on sales—which is why brands search the globe for the cheapest factories that can reliably make their clothes. Labor leaders in countries such as Bangladesh and India, which have some of the world’s lowest wages for garment workers, say there’s constant competition among factories to get those contracts, so they offer the lowest prices possible, creating constant downward pressure on worker wages.

The report asks brands to consider two major changes to this system: One, it proposes they use their leverage to get factories to raise wages to a living wage, up from the legal minimum, which large numbers of workers—more than half in some cases—don’t even get. Two, it suggests brands not multiply the wage increases through their normal markup structure.

Rather than raising the final price of the shirt in the example by €6.75, which again includes a multiplied profit, they could just raise the price by the additional labor cost of €1.34. The price tag on the garment grows far less, making it much more palatable to shoppers, while the workers benefit significantly.

It’s a simple idea, though not so simple to execute. The authors note that the entire industry needs to be on board for factories to adopt a living wage, while abandoning the current markup structure “calls for truly innovative thinking and breaking business practices in place for decades.”

Boston Consulting Group and Global Fashion Agenda created their report specifically for the May 11 annual Copenhagen Fashion Summit, which brings together industry leaders to discuss the most pressing sustainability issues facing their sector. Hopefully for workers and shoppers alike, those industry leaders will be listening.