What to expect when you’re expecting the US government to appoint a special prosecutor

After president Donald Trump fired FBI director James Comey in the middle of an investigation into Russia’s role in the 2016 election, Americans immediately began to wonder who would pick up the torch—with some calling for the appointment of a special prosecutor to examine the ties between the Trump campaign and the Russian government.

After president Donald Trump fired FBI director James Comey in the middle of an investigation into Russia’s role in the 2016 election, Americans immediately began to wonder who would pick up the torch—with some calling for the appointment of a special prosecutor to examine the ties between the Trump campaign and the Russian government.

Currently, there are four congressional committees investigating Trump’s Russia connections, including his staff’s communications with Russian intelligence officials and his decision to appoint Michael Flynn, an unregistered foreign agent, to the post of national security adviser.

Democrats are skeptical that the Republican-dominated congressional panels will follow through with any heart—the top inquiry, by the Senate intelligence committee, has devoted only nine staffers to the task, far fewer than the dozens who investigated the Benghazi attacks in 2014.

Now, leading Democrats like New York senator Chuck Schumer say Americans need a special prosecutor, a type of independent counsel, to take up the case.

What exactly is a special prosecutor, and how does one get appointed?

Special prosecutors are individuals appointed by the US Department of Justice, with the mandate to investigate a crime and bring charges. They are only used when the regular justice system is potentially implicated in or compromised by the case at hand.

The nation’s top law-enforcement officer, US attorney general Jeff Sessions, has already recused himself from matters concerning Russia because of two meetings he had with the Russian ambassador during the campaign and did not disclose. Sessions is one of a dozen Trump staffers or family members with Russia ties. The extent of Trump’s business connections to Russia is unknown because he refuses to share his tax returns with the public.

The first time a special prosecutor was appointed in the US, according to the Congressional Research Service, was during the “Watergate” investigation into president Richard Nixon’s illegal efforts to boost his re-election campaign. At the time, senators made the confirmation of a new attorney general contingent on the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate the Watergate scandal.

That’s the kind of leverage that Schumer is trying to use now with Trump, but unless Republicans join him in asking questions—or Democrats manage to take back the chamber in 2018—he will not be able to do much. So far, the president’s party has not backed a special prosecutor; the Republicans most eager to investigate, like senator John McCain, want a special congressional inquiry instead.

In the company of Archibald Cox and Kenneth Starr

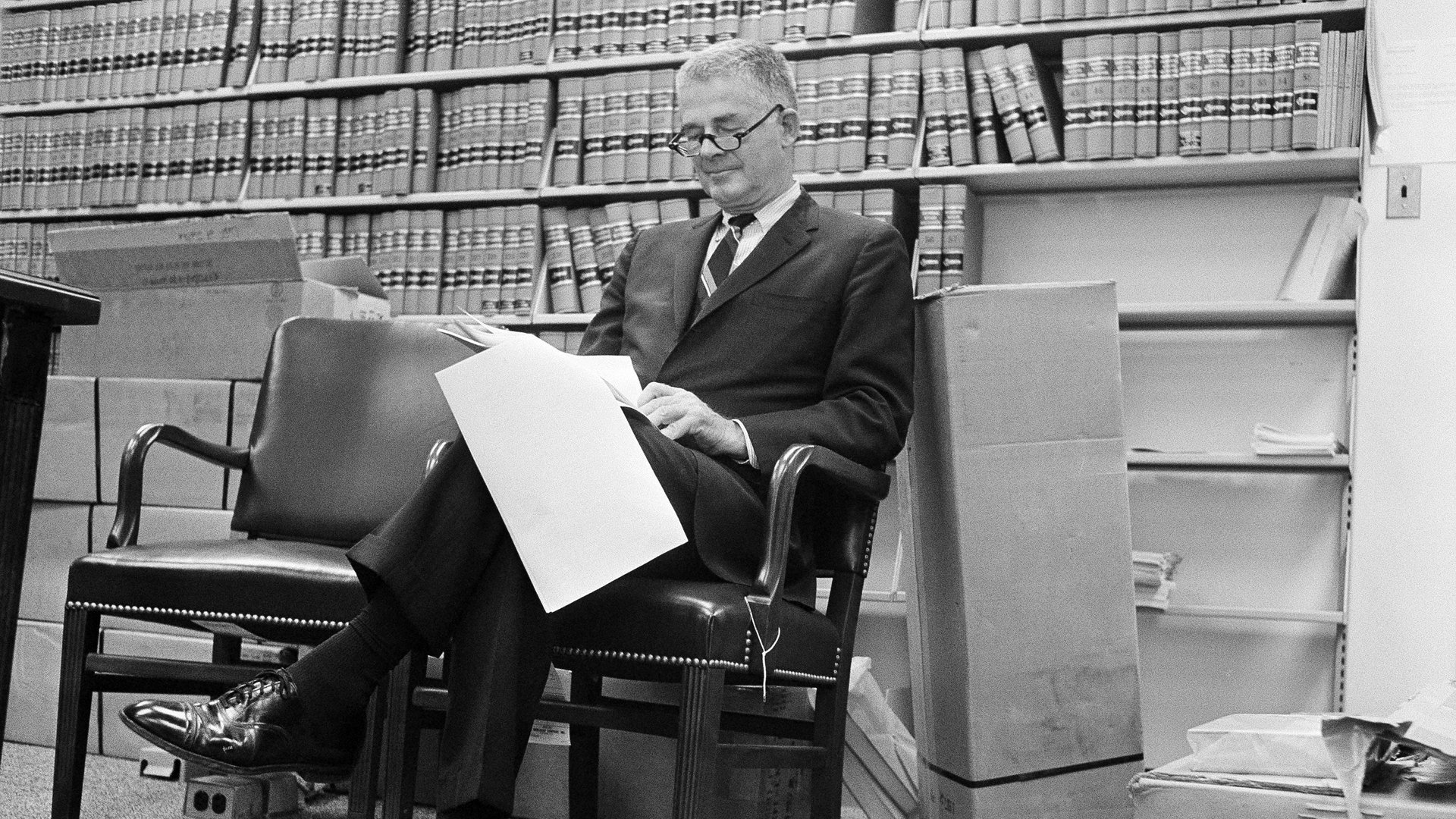

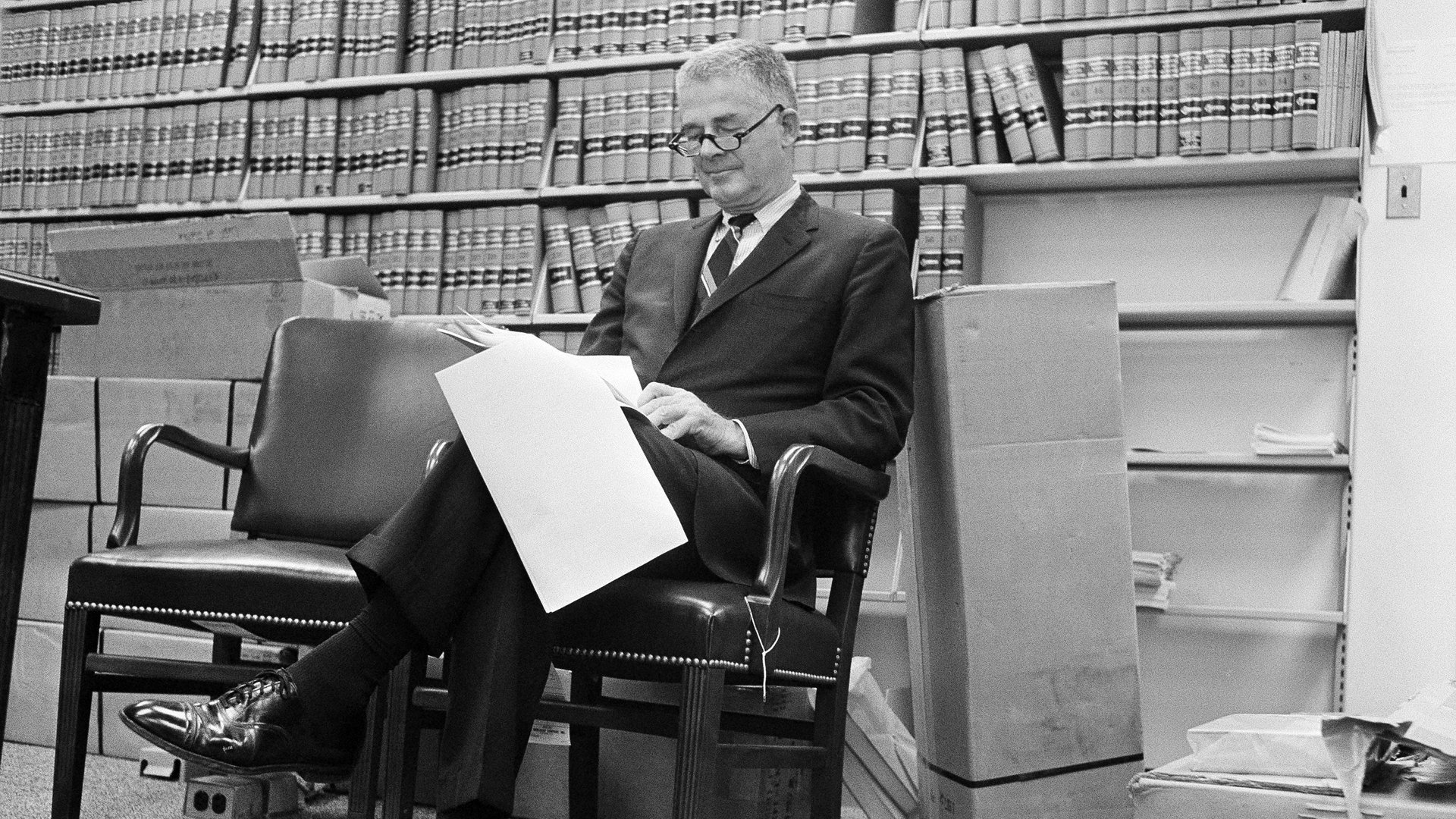

You may have heard the Nixon special prosecutor’s name, Archibald Cox, come up in the context of Comey’s firing. As Cox’s investigation proceeded, Nixon tried to fire him, but his attorney general and deputy attorney general resigned rather than do so. Though Nixon eventually found someone to carry out his order—future Supreme Court lightning rod Robert Bork—the controversy known as the “Saturday Night Massacre” horrified even Nixon’s political allies, and he would resign within a year.

Post-Watergate, Congress passed a law formalizing the use of special prosecutors to investigate malfeasance in the government. The most prominent by far has been Kenneth Starr, who investigated president Bill Clinton’s administration for a variety of scandals between 1994 and 2001. At first assigned to investigate real-estate investments made by the Clintons, the inquiry expanded to include sexual-harassment allegations, and would end with Clinton’s impeachment and acquittal for lying about his extra-marital affairs. The controversy around Starr’s behavior, which Democrats saw as a political witch hunt—and which even some Republicans saw as overreach—was one reason lawmakers let the special prosecutor law expire in 1999.

Unless Congress passes a new law, only the attorney general can appoint an independent investigator. Because Sessions has recused himself on Russia matters, that duty would fall to the deputy attorney general Rod Rosenstein, who also prepared the memo justifying Comey’s firing. Ironically, the precedent for this was set by Comey himself in 2003. Then the deputy attorney general, he assigned US attorney Patrick Fitzgerald to investigate the leaking of the identity of CIA agent Valerie Plame during the debate over the Iraq war, after attorney general John Ashcroft recused himself. Fitzgerald would go on to convict Scooter Libby, vice president Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, of lying under oath during the investigation into who revealed the classified information.