The smart home might finally get some brains

Alex Teichman thinks your smart home isn’t actually smart—it’s just remote controlled.

Alex Teichman thinks your smart home isn’t actually smart—it’s just remote controlled.

“It’s great that you can turn down the heat when you’re away at work,” he says. “But all the intelligence is coming from you. It’s not actually smart yet.”

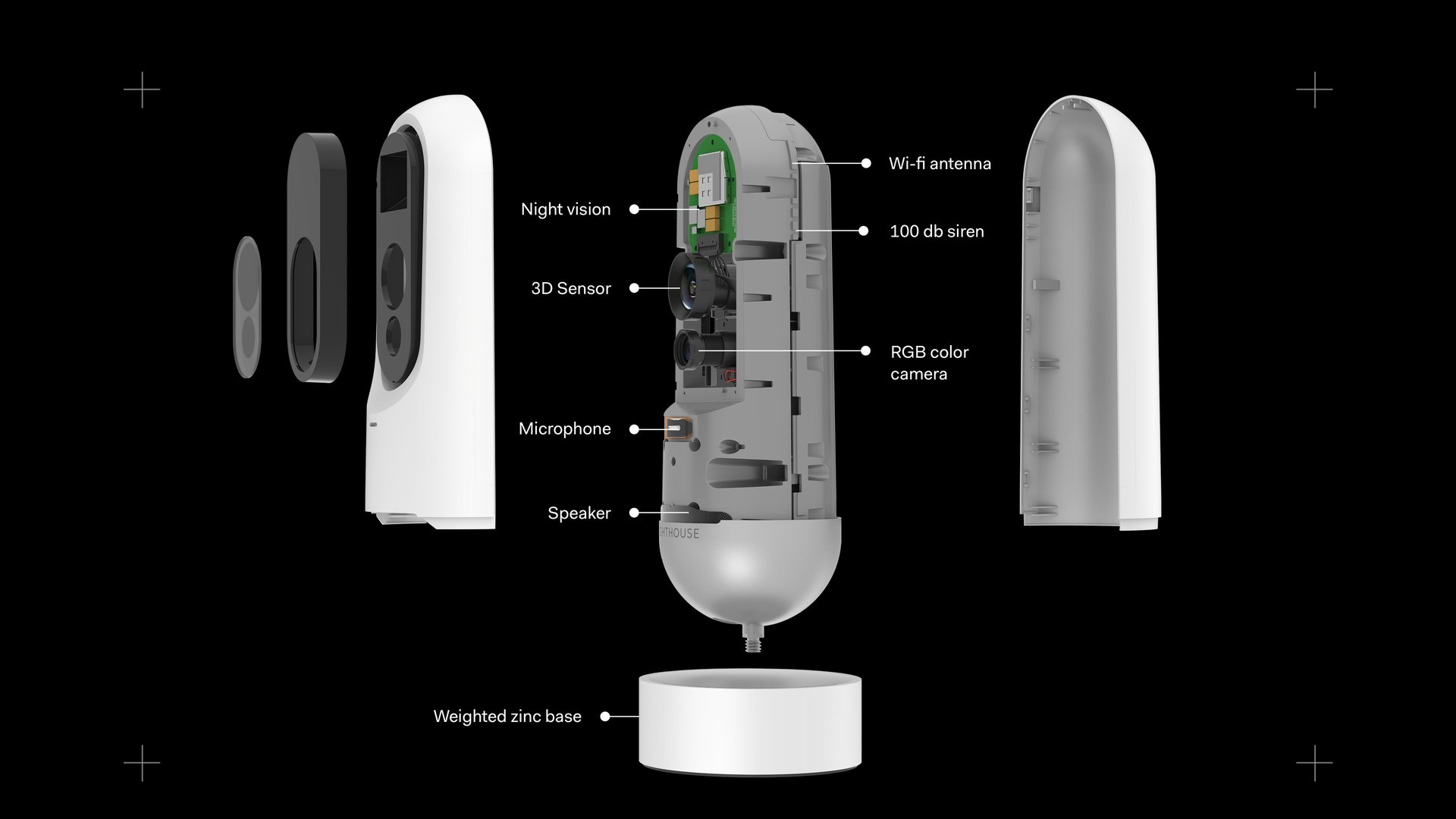

Teichman is CEO of Lighthouse, a startup out of Android cofounder Andy Rubin’s Playground incubator. The company has redesigned the home-security camera to include similar 3D-sensing technology as self-driving cars, coupling that with artificial intelligence to make sense of what’s happening. The chosen tech isn’t random—Teichman got his PhD working at famed Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun’s self-driving car lab, and his cofounder Hendrik Dahlkamp was the first Google X engineer and a DARPA Grand Challenge winner.

The company’s first product, called the Lighthouse interactive assistant, can not only detect who’s at home but also what they’re doing—running, walking, opening a door, or waving to the camera. Users can also give out complex commands, like “Let me know if the kids don’t get home between 3pm and 5pm,” and Lighthouse will understand and act accordingly.

This is the brain that the home has been missing, Teichman says—an assistant you can ask to check in on your home while you’re away or can proactively give you a heads up when something goes wrong.

Consumer technology companies have been chasing the smart home for years, but the idea really became possible in 2010 with the founding of Nest. Former Apple engineers Tony Faddell and Matt Rogers built the company’s flagship thermostat to automatically learn owners’ preferences—a relatively simple task of coordinating temperature and time.

Since then, the most successful smart-home gadgets, like the Philips Hue bulbs and Belkin smart plugs, have mainly been controlled remotely rather than with intelligence. When devices are set based around the specific time you want to get up or go to sleep, they fail when things don’t go according to plan.

Lighthouse is focused on letting you keep tabs on your home when you’re away, but the technology could have important implications when you’re inside as well. A device that can trigger actions because it understands action and intent is inherently more powerful than a device that works on a timer. It could theoretically alert police of an intruder or see that you’re walking into the bathroom with a towel in the morning and activate your coffee machine with equal ease. Perception and understanding are the answer to everything the smart home today can’t anticipate.

It also raises inevitable privacy concerns. Lighthouse says it doesn’t look at any video inside its customers’ houses until specific files are actively shared by users with the company. But AI needs data to get better, so Lighthouse also runs a beta program, where testers consent to their data being used in return for early access to new features and some input into features they’d like to have.

Putting an internet-connected camera in your home might have seemed ridiculous a few years ago, but the security-camera market actually accounted for 61% of all home-automation revenue in 2015, according to research from NPD. That means Lighthouse is entering a crowded market, with competitors ranging from startups like Canary to Alphabet, which now owns Nest. Those products typically rely solely on cameras rather than the photoelectric sensor used in Lighthouse, which also allows night vision. Rather than having to calculate the shape and distance of objects from video, the sensor bounces its own invisible light off objects to gauge that directly, giving better data for the AI to then understand what it’s looking at.

And that, Teichman says, allows for nuance that other smart-home cameras can’t achieve today.

“It understands the 3D environment,'” he says as he describes how Lighthouse processes an unknown person in a house. “‘Oh hey, there’s something new here. I don’t understand what this is, it’s physically large enough that it might be a person, I better tell someone about this.'”