The prom dress: An anthropological history of America’s sexual coming-of-age costume

A strange ritual takes place across the United States each spring. It shares elements with the Hindu marriage ceremony, in which the young bride is wrapped in a red sari, and joined with her life-mate amid elaborate festivities. Or Japan’s Seijin-no-Hi, when young women adorn themselves in beautifully detailed kimonos and men don their smartest suits. Or the Ghanaian puberty rite of Dipo, in which girls wear ceremonial cloths as part of their initiation into womanhood each April and May.

A strange ritual takes place across the United States each spring. It shares elements with the Hindu marriage ceremony, in which the young bride is wrapped in a red sari, and joined with her life-mate amid elaborate festivities. Or Japan’s Seijin-no-Hi, when young women adorn themselves in beautifully detailed kimonos and men don their smartest suits. Or the Ghanaian puberty rite of Dipo, in which girls wear ceremonial cloths as part of their initiation into womanhood each April and May.

During those same months across the US, young people gather for a dance sanctioned by local elders, where they dress in fancy costumes that embody traditional gender tropes and old-fashioned notions of sexuality, to celebrate their transition from childhood to adulthood. The Americans call it prom.

High school prom, a celebration of teens as they graduate from high school, is widely regarded as a defining feature of the American adolescent experience, though it also takes place in Canada and has spread overseas. It can seem like a curiously outdated ritual, especially to those who have never gone to one (and to many who have). Its rules and conventions have their roots in the debutante balls of generations long past, and have been codified over and over in TV shows and movies, including teen classics such as Pretty in Pink, Sixteen Candles, She’s All That, and 10 Things I Hate About You (and even the horror movie Carrie).

But prom is also much more than that. It’s now a rite of passage in the social life of kids in the US, and over the decades it has been a space where teens navigate—and push back against—societal conventions about gender, sexuality, tradition, and values.

That process is evident in the clothes. To understand what’s really going on at prom, just take a look at the sartorial centerpiece of the whole experience: the prom dress.

The many meanings of a prom dress

Whether or not kids or their parents realize it, the prom dress is an exercise in balancing different social tensions: the need to fit in, but also look like yourself; the need to look classic but also modern.

Sociologist Amy Best, an expert in youth culture at George Mason University, laid out the challenge of picking the right dress in her book Prom Night: Youth, Schools, and Popular Culture, which drew on extensive interviews with students:

A range of factors must be considered: not only must she set herself apart through what she wears at the prom, the dress must also be remembered in a particular way. It must be able to endure changing styles and outlast current trends. She is conscious not to make the same mistakes as other girls. Her good taste, keen sense of style, and feminine judgment will be admired not only at the prom, but in years to come. How she remembers the prom is contingent on how she remembers the dress.

Girls can spend weeks of careful deliberation picking their dress. In the pressure cooker of teenage society, the stakes are high, particularly compared to those faced by their male counterparts, who for the most part wear a fairly standard tuxedo or suit, with some variation mixed in.

But for girls, the dress is much more an opportunity for them to display how they see themselves, and want others to see them. For many, that often includes a distinct whiff of sexuality.

It makes dad uncomfortable, but that’s the point

The event is one of the first instances where girls and boys are allowed, or even expected, to act as an ”adult”—often hiring a limousine with friends, going out to dinner, and drinking alcohol. It’s common to see girls in dresses with slits climbing up the legs, open backs, and diving necklines.

“I think that an undertone to girls’ dress is issues around sexuality,” Best explains. ”The prom is a place where young women are able to try out different ways of being sexy in a limited liability contest.”

The rags-to-princess Cinderella tale is a recurring theme in all those prom movies, and transformation is the subtext to the whole affair, particularly for girls. The dress plays a crucial role, as Best explains in her book.

“The prom dress is critically important to this invention of a sexual self,” she writes, adding, “I also overheard many girls proudly exchanging stories of their fathers’ utter discomfort in seeing their daughters in such sexy dresses, testimonies that the girls had succeeded in transforming themselves.”

But this all takes place within a fairly rigid framework. The typical dress today—a fancy floor-length number with an embellished bodice, featuring beads, stones, lace, or embroidery—is the direct descendant of the princess-esque gowns that wealthy debutantes wore for their “coming out” balls, the sorts of promenades that give prom its name.

Of course, the premise of the debutante ball was parents of the upper crust introducing their daughters to society in a setting, and in clothing, they deemed appropriate. Since the middle class adapted the ball for its more democratized “proms,” which first emerged at US universities around the turn of the 20th century before gaining wide popularity by the 1930s in high schools, dress and conduct codes have sought to safeguard that propriety.

The dress needs to balance tradition and the romantic script of adolescent dating—again, the same seen in many a fairytale and prom movie—with the desire to be sexually attractive. That floor-length dress, for instance, may flash skin in ways that are hardly scandalous on a red carpet, but still overtly “adult” at prom. It’s another interplay of tensions.

The style of the social-media generation

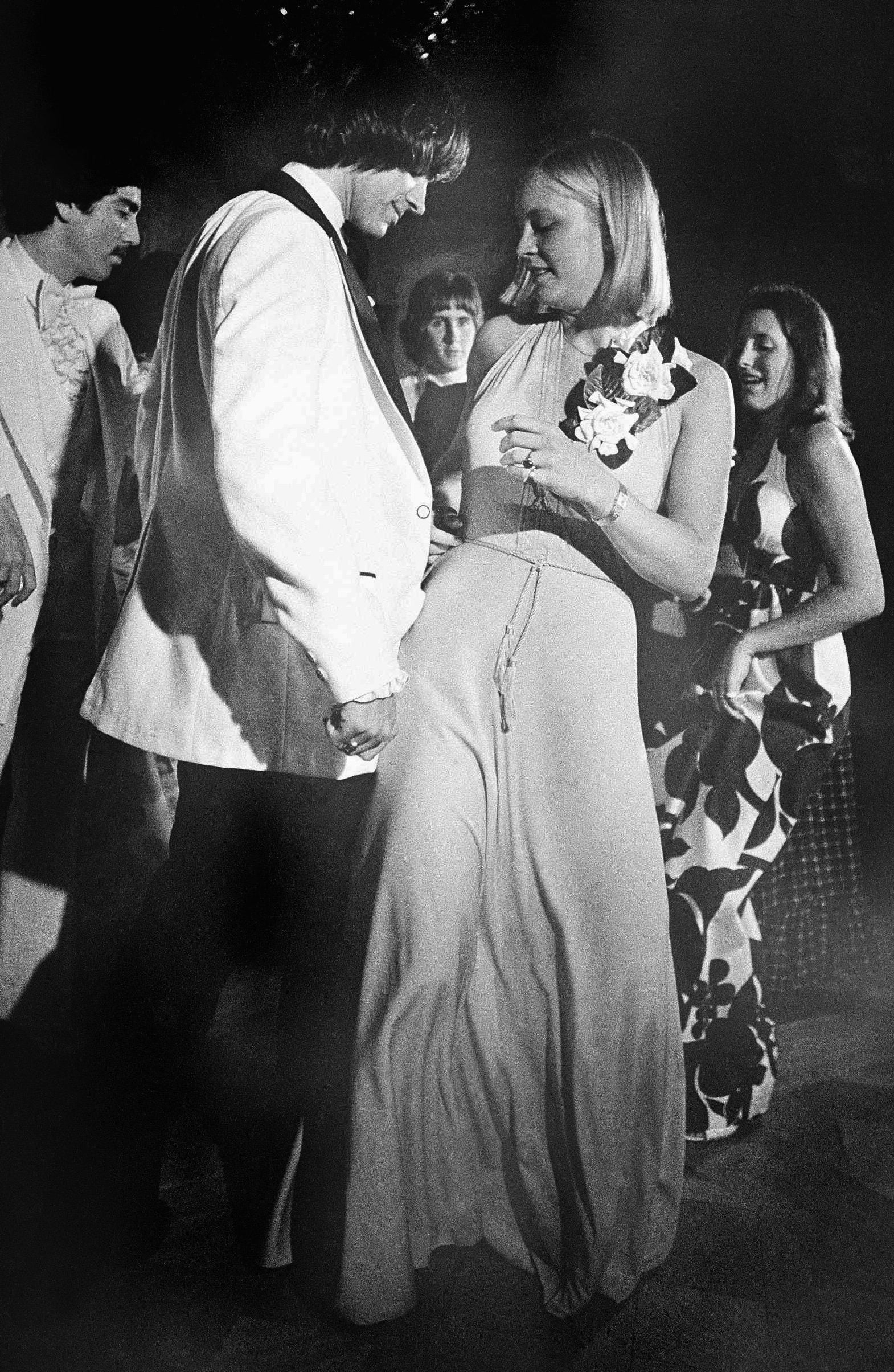

In the 1950s, there were full skirts, which gave way to the empire waists of the 1960s. Flounces and ruffles dominated the 1980s, while the 2000s were heavy on slinky sheaths.

Social media now shapes the way prom looks, says Kaye Davis, vice president of fashion business development for World of Prom, a large tradeshow for prom-dress retailers. The high school seniors really tend to mimic celebrities and what they see trending on social media,” she says. “This generation is probably more on-trend and willing to push the boundaries.”

The details that will define the dresses of this era, in Davis’s opinion, are two-piece looks that often show off the midriff; skirts with high slits; and short skirts with a lace overlay that reaches the floor—which allow the wearer to have it both ways, keeping the dress on the conservative side while showing off a glimpse of her legs.

What apparently hasn’t changed much in recent years is the cost. While dresses can range from about $100 to beyond $800, Davis estimates that the average people spend is around $200.

Documenting prom night, and the prom dress, remains an important part of the ritual. The often-awkward ritual of photographing the couple, corsage on hand, as they set out on their big night, has now migrated to Instagram and Snapchat. Buildup to the evening often includes a stream of images including shoes, accessories, and hair and makeup, hinting at the complete prom look. The same goes for the emerging custom of the “promposal,” in which a boy (in most instances) asks a girl to prom in some elaborately staged, and increasingly expensive, scenario.

Best has noticed one other big change in recent years, which is more diversity in what boys choose to wear. Since the 1990s, the tuxedo styles and color combinations boys sport at prom have expanded. It’s now much more common to see tuxedos with mandarin collars or contrasting lapels, and jackets in gold, red, gray, or midnight blue.

Resistance in a dress—or a tux

An increasingly diverse contingent of American kids see prom as an opportunity to convey their identities, Best says. In recent years, the white, heteronormative paradigm handed down from those debutante balls has given way to something much more representative of what American kids are like today. A wider mix of cultures, as well as sex and gender identities, are evident in the clothes of prom, too.

Of course, this isn’t entirely new: For generations, young people have challenged the norms of standard prom clothing. There always seems to be at least one person in a powder-blue tuxedo or a dress made of duct tape.

These are the “resisters,” as Best calls them. “How kids fashion themselves, the styles they wear, are often used to respond, to reject, to ‘talk back’ to dominant culture,” she writes, borrowing the “talking back” metaphor of feminist author bell hooks.

Today much of that talking back is tied to gender and sexuality. Because the dress code at prom is so strictly regimented and binary—male students wear tuxedos, and female students wear dresses—it turns the event into an arena for students to confront those conventions.

For some girls, the perfect prom outfit isn’t a dress at all, though such choices still encounter hostility in parts of the US. Last year a lesbian high school student in Pennsylvania was banned from her prom because she wore a tuxedo.

It’s a testimony to the significance of the event that gay and transgender students have been battling restrictions on being themselves openly at prom for decades—at least since 1980, when a student named Aaron Fricke sued his Rhode Island school for the right to attend prom with his boyfriend.

But the culture of prom is changing. In recent years several trans students have been voted their schools’ prom queens. And just a few weeks ago, Alan Belmont became the first trans prom king at his Indiana high school.

Belmont wore a burgundy tuxedo jacket with black lapels that matched his date’s black dress, a halter style with a long slit up the side. They looked great.