Inside the digital heist that terrorized the world—and only made $100k

Robert Gren had 26 minutes left to decide whether to pay the ransom. It was Monday, May 15, three days after the global cyberattack now known as WannaCry had begun, and a clock on Gren’s computer screen was counting down.

Robert Gren had 26 minutes left to decide whether to pay the ransom. It was Monday, May 15, three days after the global cyberattack now known as WannaCry had begun, and a clock on Gren’s computer screen was counting down.

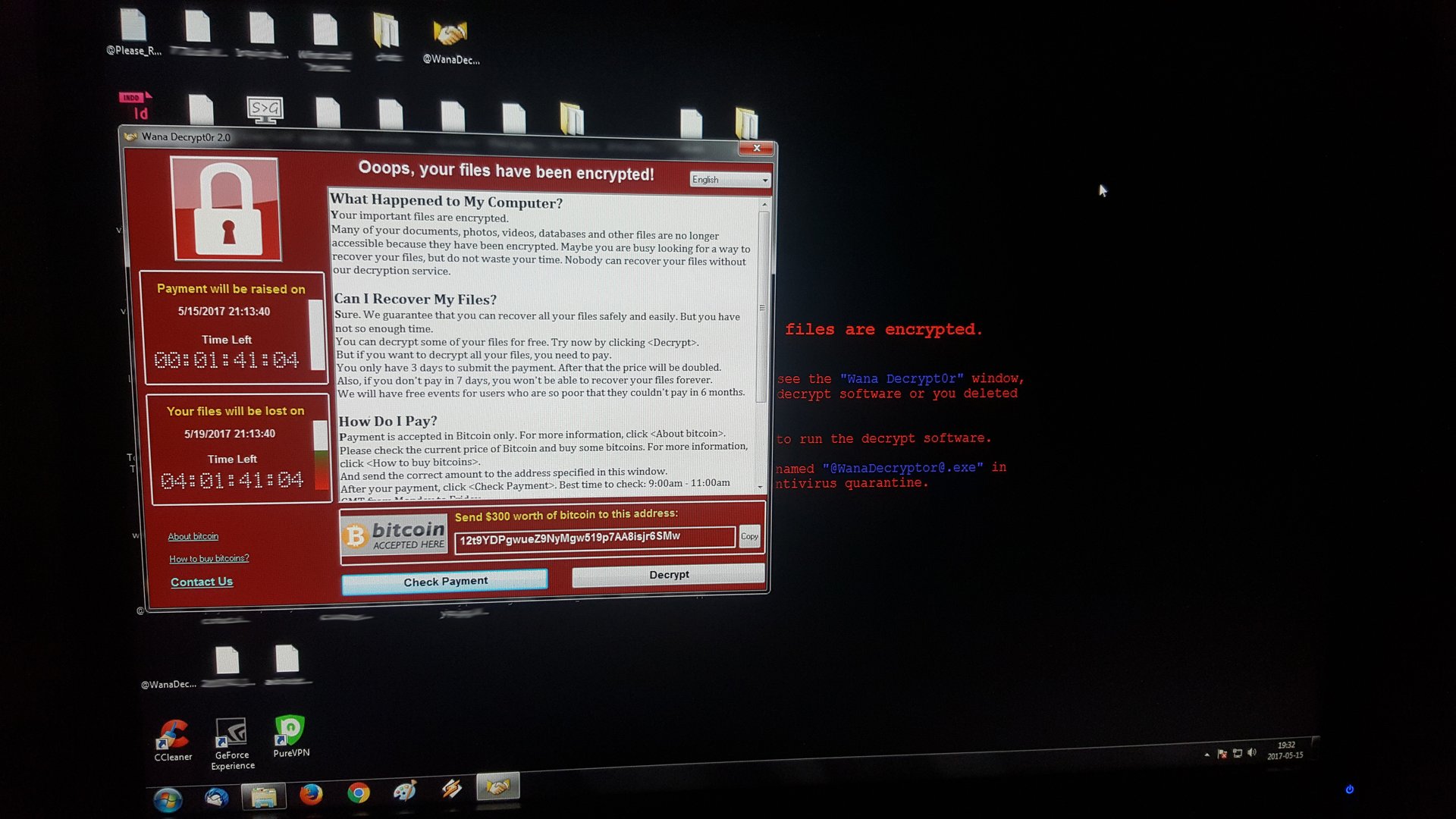

Above the clock, there was a warning: “Payment will be raised on 5/15/2017 21:13:40.”

The ransomware on Gren’s desktop computer had encrypted his files and demanded he pay $300 in bitcoin to get them back. In 26 minutes, the price would double. He was willing to pay, because the files he’d lost represented his entire digital history: family photos, work files, music. It would all be gone. But he didn’t believe the hackers would decrypt his files even if he paid.

“I’m still battling my thoughts,” he said over the phone as he watched the clock ticking down. “I have found some people that claim that their friends or acquaintances have had their files decrypted. But on the other hand, I haven’t been able to verify it in any way or get in touch with anyone directly.”

Three days earlier, when the screen had gone black on Gren’s home computer, a desktop running on Windows 7, he didn’t think much of it. It was 4 p.m. in Kraków, Poland, where Gren, 32, works from home for an online entertainment company. He assumed the sudden black screen was an innocuous glitch, and turned the computer off and back on.

The ransomware that had just found its way onto Gren’s desktop was simultaneously installing itself onto tens of thousands of other Windows computers across Europe, Asia, and parts of North America. About 30 minutes after Gren’s screen had gone black, the National Health Service in the U.K. announced that computers in 16 of its health facilities had been infected. Doctors were unable to access patient records and emergency rooms were forced to turn people away.

Soon, it was 33 facilities. Then there was a telecommunications company in Spain, a cell phone carrier in Russia, and the French automaker Renault. Anyone using certain versions of Windows that hadn’t been updated within the last month was vulnerable. Within hours, it was being called the most successful ransomware attack of all time.

As reports of new infections in dozens of countries surfaced, and it seemed the outbreak could become an all-out epidemic, a 22-year-old security researcher in the UK made a quick decision. The researcher, who goes by the pseudonym MalwareTech, had gotten a copy of the ransomware program from a friend, and ran it in a test environment on his computer. He noticed the program was trying but failing to reach a web address, a long string of random letters with a dot-com extension.

A blog post by Talos, Cisco’s threat intelligence team, later noted that the address looked like it was typed by a human, rather than generated by a computer, “with most characters falling into the top and home rows of a keyboard.” MalwareTech looked up the address and it was unregistered, so he registered it. It turned out that the URL itself was a sort of kill-switch. Whoever developed the ransomware had programmed it to shut down if it was able to access that address.

Within seconds, the ransomware immediately stopped copying itself to new computers. The young researcher had made quick work of the malicious software, but for those whose computers had already been infected, it was too late.

In Kraków, an hour after Gren had restarted his computer and gotten back to work, the screen went black again. Again, he turned it off and on. When he logged back in this time, the icons on his desktop had become empty white rectangles. The file names below them now ended with the extension “.wncry.” Gren opened some folders, and the files in each of them had the same “.wncry” extension. His heart started to race. He tried to open some of the files, but nothing happened. He managed to open a text file in Notepad, but it was all gibberish. Before long, a red window popped up on his screen.

“Ooops, your files have been encrypted!” it said. The name in the title bar in the top left of the window was “Wana Decrypt0r 2.0.”

At about the same time, in a suburb outside of Seattle, Washington, Mark Pendergraft had just finished vomiting. He’d left work that morning with a stomach flu, but now his business partner was texting him. Something strange had happened to the files on the server at their office, Mead Gilman & Associates, a small land-surveying firm. At the end of the file names, a new extension had appeared: “.wncry.”

Pendergraft, a 34-year-old partner at the firm, did a Google search for the extension and scanned a few pages, then called his business partner back. “Immediately shut down the server,” he said. He knew this would mean the office couldn’t function for the rest of the day, and the staff would have to be sent home.

Pendergraft hung up the phone, and resumed vomiting.

As security researchers and observers on social media and blogs disseminated information about the ransomware throughout the day, a shorthand for the attack emerged. Wana Decrypt0r 2.0 was also known as “WannaCrypt0r,” “WCrypt,” and “WnCry,” and by noon on the first day of the attack, security experts on Twitter had a name for this new strain: WannaCry.

Although the attack will be remembered by a name derived from the ransomware tool itself, it was not Wana Decrypt0r that enabled the rapid proliferation that distinguished this attack from others. The WannaCry ransomware represents a collection of malicious software, including a backdoor-implanting tool called DoublePulsar, and a software exploit called EternalBlue.

On March 14, before the names DoublePulsar and EternalBlue were known to the public, Microsoft released a critical security update, MS17-010, for nearly every modern version of its Windows operating system. Everything about the patch seemed normal, except for one detail. Unlike nearly every security update Microsoft puts out, this one didn’t include a credit to the researcher who discovered the vulnerability that this patch fixed.

One month later, to the day, a group calling itself the Shadow Brokers dumped a large cache of hacking tools to the public, which included software that exploited various security holes. The group claimed it had stolen the cache from the US National Security Agency (NSA). One of the tools it included was DoublePulsar. Another was EternalBlue, an exploit that targeted the Windows vulnerability Microsoft had patched in its MS17-010 release a month earlier.

Of course, the NSA hasn’t confirmed that the tools came from its agency, and Microsoft hasn’t said whether the missing credit in the release belongs to the NSA. But among security experts, it’s widely believed that they did and it does.

The Shadow Brokers’ release, according to Charles McFarland, a senior research scientist at McAfee, “provided enough information for the [malicious software it included] to be quickly added to publicly available tools within days.”

When the WannaCry outbreak began on May 12, DoublePulsar and EternalBlue had been in the wild for nearly a month, and security researchers had warned that these powerful tools could be used to devastating ends. The DoublePulsar backdoor had already been implanted by hackers in at least 400,000 computers by the time the outbreak began. And although Microsoft had released a patch for EternalBlue two months earlier, many had not installed it. The nature of WannaCry’s speed and efficiency quickly made it clear to researchers that it was using both tools.

No one had to click a link in a phishing email or visit a sketchy website to contract the WannaCry ransomware. The program is able to copy itself from one computer to another on a local network, and even over the internet, with no human interaction required. Once it worms itself into a computer, it immediately gets to work, executing one malicious command after another.

First, it executes a program called tasksche.exe, which checks whether the kill-switch web address is active. If it isn’t, WannaCry proceeds to the next step: scanning for more vulnerable computers. It checks the local network first, then generates random IP addresses to scan computers over the internet. It tries to connect to each IP address checking to see if it has a particular port open, one numbered 445. When it successfully connects to another computer, it makes a copy of itself and transfers that copy over. Then the malware gets to work taking control of the computer it’s on, first by using EternalBlue. If it’s lucky, it’s on a vulnerable Windows computer that hasn’t been updated since Microsoft released its patch for EternalBlue in mid-March.

This is when things get bad for the owner of the infected computer. Here, WannaCry uses EternalBlue to trick the Server Message Block (SMB)–which is a service on Windows that lets users on a network share files and other resources with each other–into thinking the malware is a legitimate resource, allowing it to implant the DoublePulsar backdoor. Now the malware has full access to the computer, and begins encrypting its files. When it’s finished, it displays the ransom note.

By the evening of May 12, Robert Gren had shut down his infected computer and opened his alternate laptop to search for answers, trying every combination of keywords he could think of. “WnCry ransomware.” “WnCry 2.0.” First, he wanted to find a way to decrypt the files himself. “WannaCry decryption.” “How to decrypt.” Then, he just wanted to know if he’d get his files back if he paid the ransom.

“I’m not really present in any social media,” Gren said. “I don’t have an Instagram. I don’t use my Facebook. I guess I’m just a private person.” But that Friday night, he created a Twitter account in an attempt to find some hope, to find someone who had paid the ransom and regained access to their files. He came up empty. He went to bed at 1 a.m., but lay awake for hours.

“I could not turn my brain off,” he said over the phone. “I couldn’t stop thinking about what happened. I tried to figure out what else can I do. What different approach can I take.”

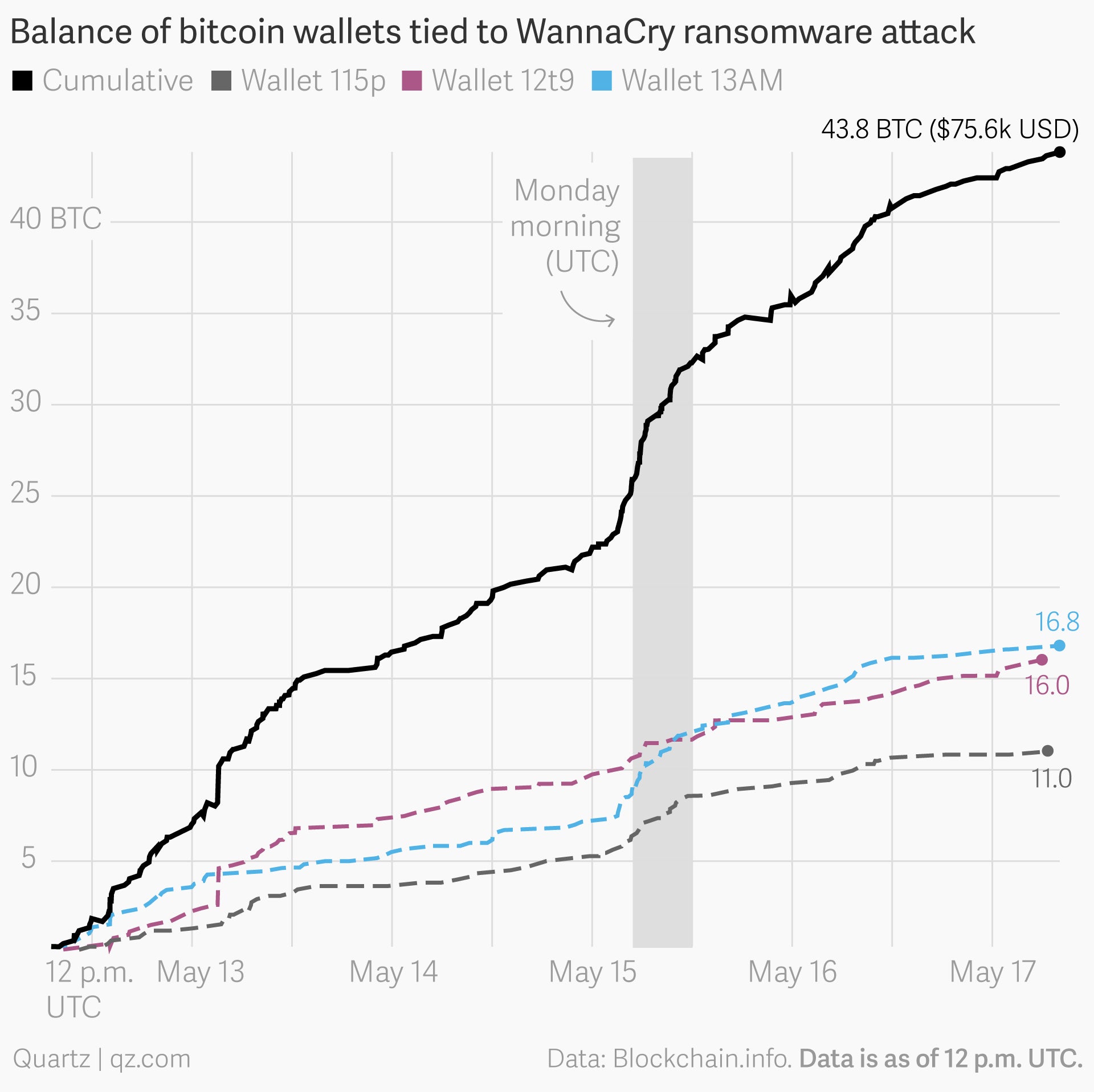

As that Friday ended, WannaCry was no longer spreading, but more than 80,000 computers had been infected, according to a tracker setup by MalwareTech, and victims had already started to pay the ransom. The message on each victim’s screen demanded they send either $300 or $600 to one of three bitcoin addresses.

All bitcoin addresses have associated accounts, typically called wallets, which are accessible to the public. And because this particular ransomware program used just three wallets, the whole world could easily watch as they started receiving payments. A total of 36 payments between $250 and $600 dollars went into those three wallets on that first day.

The use of only three bitcoin addresses made it easy for onlookers and law enforcement to watch the wallets, but it also appears to have made it difficult for the attackers to know which victims had paid, and which had not. In past attacks, more sophisticated ransomware programs dynamically generated a new bitcoin address for each machine they infected, so that the process of decrypting the computers of victims who had paid could be automated. If money hits X address, victim Y gets decrypted.

Using just three wallets, on the other hand, indicates the hackers behind the attack may have had to manually provide decryption to any victim who paid, perhaps by using the ransomware’s built-in messaging system that allowed the victims to communicate with their attackers. If the goal of ransomware is to extract money from its victims, the functionality to collect payments is as important as the code that allows the malware to spread, and this payment system seemed as if it were built by amateurs.

It was a choice that confounded experts, as was the hackers’ decision to build-in a kill-switch URL. Both seemed like rookie mistakes, incongruous with the level of sophistication of the rest of the malware. It appeared that the developers of the payment system didn’t know what they were doing, or that the attack was about something other than money.

“There are several odd decisions made by the WannaCry developers,” said McFarland, McAfee’s research scientist. “It is not built like ransomware we generally see in the wild.”

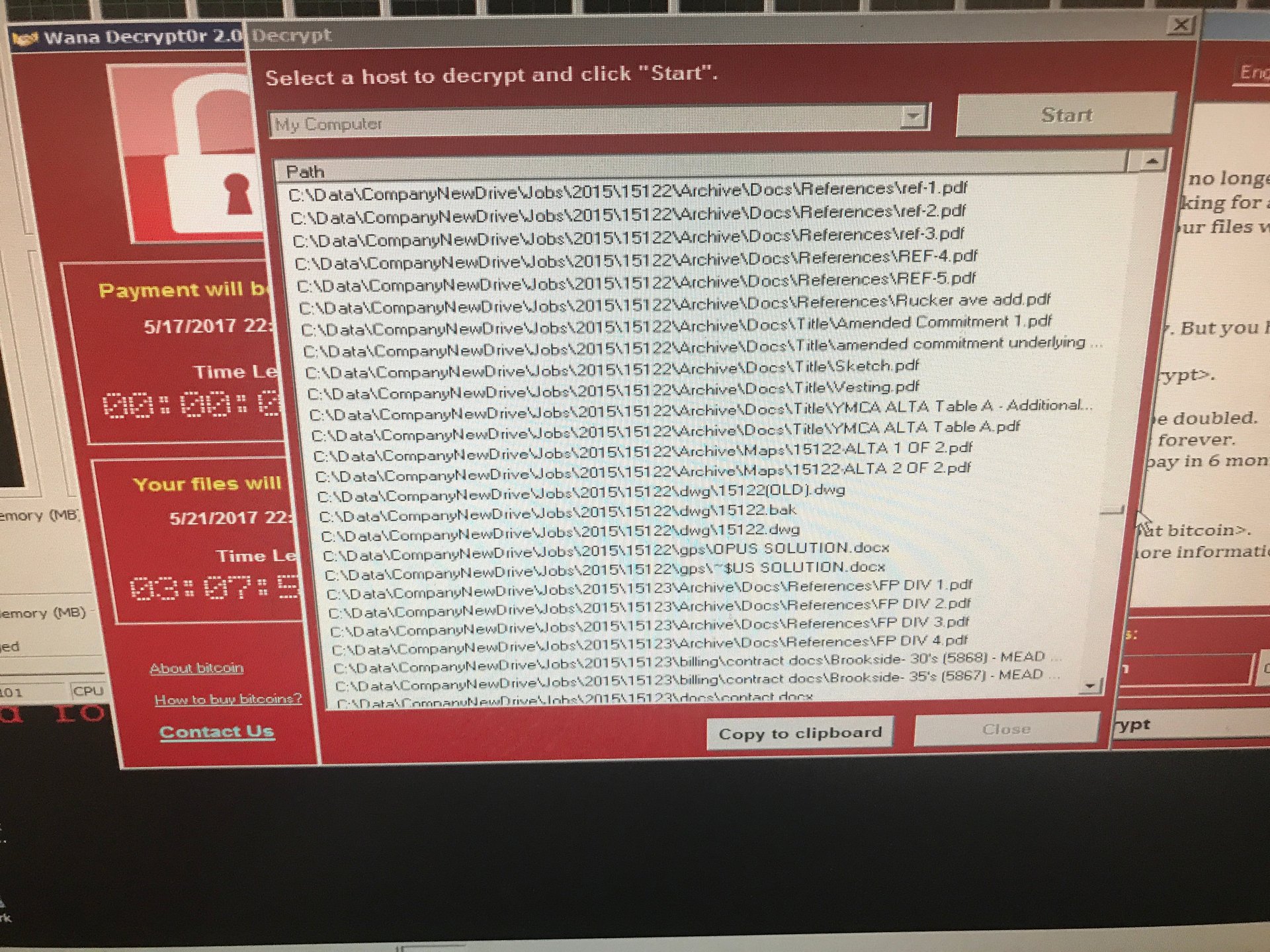

By Saturday, May 13, Mark Pendergraft was no longer throwing up. He went to his office to meet his business partner, Shane Barnes, to assess the damage. Most of the files on their Windows SBS 2011 server had been encrypted. They had unknowingly been using an expired credit card for their cloud backup account, and it had lapsed. The red Wana Decrypt0r window demanded $600. They consulted their IT contractor, and he said there was nothing he could do.

Pendergraft and his partner decided to pay the ransom.

“Shane starts researching how to buy bitcoins and sets up a wallet,” Pendergraft said in an email. “He goes to CoinBase and they tell him he can only exchange $500 for bitcoin a week, and only then if he uploads his ID.”

Barnes uploaded his ID to the website and deposited $500, then took $200 to a bitcoin ATM, where he could deposit directly to his wallet. That evening, Pendergraft and Barnes made their payment to the wallet address listed on their copy of Wana Decrypt0r 2.0. And then they waited.

In Kraków, Gern spent his day researching, still trying to find evidence that he’d get his files back if he paid the ransom. On Twitter, he messaged experts who had tweeted that some people were able to get their files after paying. But they either didn’t respond or told him they didn’t know the people directly.

Gern took a break in the afternoon to see “Alien: Covenant.” He didn’t like it.

He decided to click the “contact us” button on Wana Decrypt0r. He sent a message saying that he had paid the ransom, even though he hadn’t. He clicked on a button that said “check payment,” which is purportedly the way victims are supposed to get their files decrypted after they pay. Researchers have said the functionality of the button is dubious. A message popped up: “You did not pay or we did not confirm your payment!” Then, further curious instructions: “Pay now if you didn’t and check again in 2 hours. Best time to check: 9:00am – 11:00am GMT from Monday to Friday.”

He went to bed late again that night, and again he couldn’t sleep.

Gern’s Sunday was much the same as his Saturday. He researched without luck. He sent another message, saying again that he had paid and wants his files back. He clicked the button and got the same message. He took a walk in the afternoon, and enjoyed it more than he had the Alien movie.

In Seattle, Pendergraft and Barnes had to wait for Wana Decrypt0r to finish encrypting more files before they could interact with it. When it finished encrypting, the window was now asking for $300, even though they had already sent $600. When they clicked the “check payment” button, they received the same message Gern had: “You did not pay or we did not confirm your payment!” Try again in two hours, best to try between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m. GMT.

“We obsessively hit this button the first few days,” Pendergraft said in an email. “There is also a ‘contact us’ button which brings up a small dialog with a text box. I sent about 6 or 7 messages over the week stating that we have paid and please help us decrypt our files. I mentioned my email address in one of them, not knowing how they would contact us, and I also mentioned that we had paid double their ransom.”

The next day, Monday, May 15, Gern had 26 minutes left to decide whether to pay the ransom. In 26 minutes, the price would double to $600. For the past three days, he’d been agonizing over the decision. It wasn’t so much about the money. If he paid and didn’t get the files back, he’d feel like he’d been duped into donating cash to a criminal enterprise.

“I struggled. I struggled really hard. I kept asking my fiancee for advice,” he said.

“What should I do? I don’t know what to do. Should I pay?” he’d ask his fiancee.

“I still haven’t found any verified source that paid and recovered the files,” he’d say.

“What do you think?” he’d ask again.

“Then after I ask her 10 times she says pay just for the sheer fact that I leave her alone finally,” he said.

When the clock reached three minutes, Gern decided to go out to his balcony to smoke a cigarette. He was worried that if he stayed near the computer, he’d break under the pressure and pay the ransom. When he returned to his computer, there were 30 seconds left. He watched as the clock hit zero, and as the price increased to $600. Then another timer started, giving him 72 hours to pay the higher price. If he didn’t, Wana Decrypt0r would delete all of his files.

He sent another message through the “contact us” button, again trying to convince the hackers that he’d paid the ransom.

Pendergraft and his partner spent Monday continuing to send messages and clicking the “check payment” button, getting the same message every time. “You did not pay or we did not confirm your payment!” By Tuesday, 176 payments of $200 or more had hit the three bitcoin wallets Wana Decrypt0r used. One of those was the $600 Pendergraft had sent, but his experience had nonetheless been very similar to Gern’s.

“Basically, all hope is lost at this point,” Pendergraft said. “I spent a lot of time searching online for other users who paid the ransom and had their files decrypted. I was unable to find a single instance of someone personally stating that they were successful in decrypting.”

The next day, Pendergraft hit the “check payment” button again, and a different message appeared.

“Your payment was received. Start decrypting now.”

A new window popped up, and it started scrolling through the files, decrypting them all.

“I pretty much screamed for joy,” Pendergraft said.

Things at Mead Gilman & Associates could finally go back to normal. Except for a worrisome server crash later that day, all was well. But there was one oddity about the ordeal that continued nagging at Pendergraft: in his messages to the hackers, he had never provided proof that he and Barnes had sent the $600, and the hackers never asked for it. Just like Gern, all they had done was send messages to the hackers, claiming they paid.

In fact, there is no clear way that anyone who paid could prove that they did. They could give the hackers the unique bitcoin address that they sent the money from. But Pendergraft pointed out that even that would be meaningless, because anyone could view the wallets online and see the addresses that each payment came from.

“I don’t know if they took our word for it, or if they just randomly decrypted some people’s files so that word would get out that paying your ransom actually resulted in decryption, or if they had some other means of detecting payment,” Pendergraft said. “I did hit the contact form several times and stated that we paid, and that I could prove it. But I never actually provided them with the wallet address that we paid from.”

All told, the three bitcoin wallets used in the attack have received just under 300 payments totaling 48.86359565 bitcoins as of Saturday evening, the equivalent of about $101,000 USD. That’s a small take for an attack that infected nearly 300,000 systems, made medical care inaccessible, shut down factories, and ultimately may have created billions of dollars in losses.

Some have attributed the low rate of return to the ubiquity of cloud services. Someone who keeps their most important files on Dropbox or Google Drive could simply erase their hard drive and re-install their operating system if their computer were infected. There’s also the difficulty of using bitcoin, or running into the $500 deposit limit as Pendergraft and Barnes did.

And then there’s the payment system, or lack thereof. Many people infected with ransomware will do some research about whether they’ll get their files back if they pay. And in the case of WannaCry, there was little good news to be found. Here’s a system that uses only three bitcoin addresses, and seems incapable of knowing whether someone paid their ransom.

Given that, the entire operation may appear to have been run by amateurs, hacking novices who downloaded some powerful software that someone else had stolen from the NSA, and botched the most important part of the operation: making money. But Raj Samani, a security engineer at McAfee, advises caution on that estimation.

“There is more to this than meets the eye,” he said. “We currently are analyzing the payment mechanism and believe that this campaign has many elements to it that deviates from our normal understanding of ransomware.”

On Thursday, a little before noon in Kraków, Gern took a break from his work to make himself some coffee. He still hadn’t paid, but had continued to send messages through the “contact us” button throughout the week, and had gotten into the habit of clicking the “check payment” button every day.

“On my way to the kitchen to get the coffee, I turned the computer on,” he said. “I came back with coffee, and I clicked the button, and there it was.”

“Your payment was received. Start decrypting now.”