Reality check: Impeaching Trump is very hard, even if he did ask Comey to end the Flynn investigation

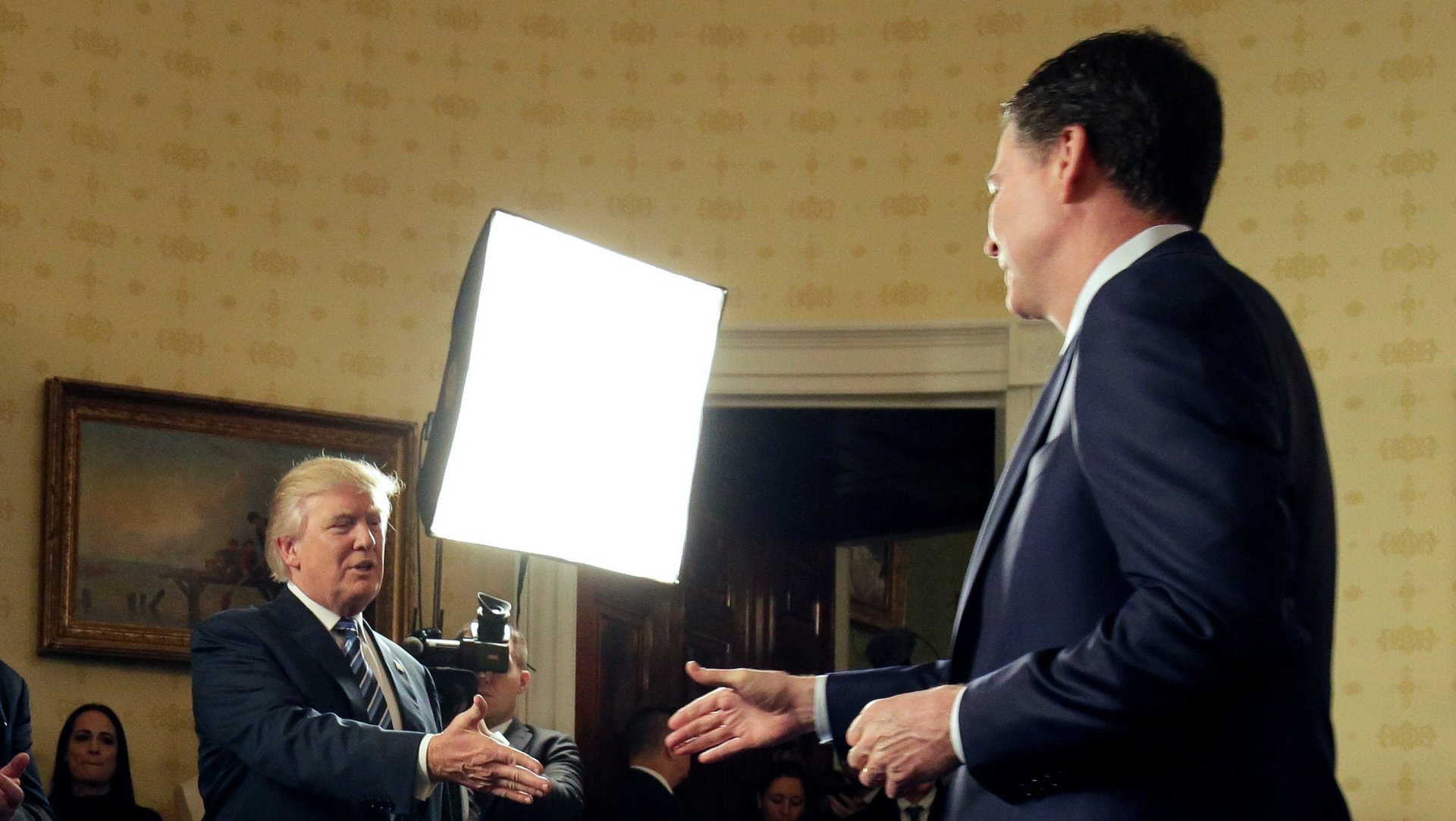

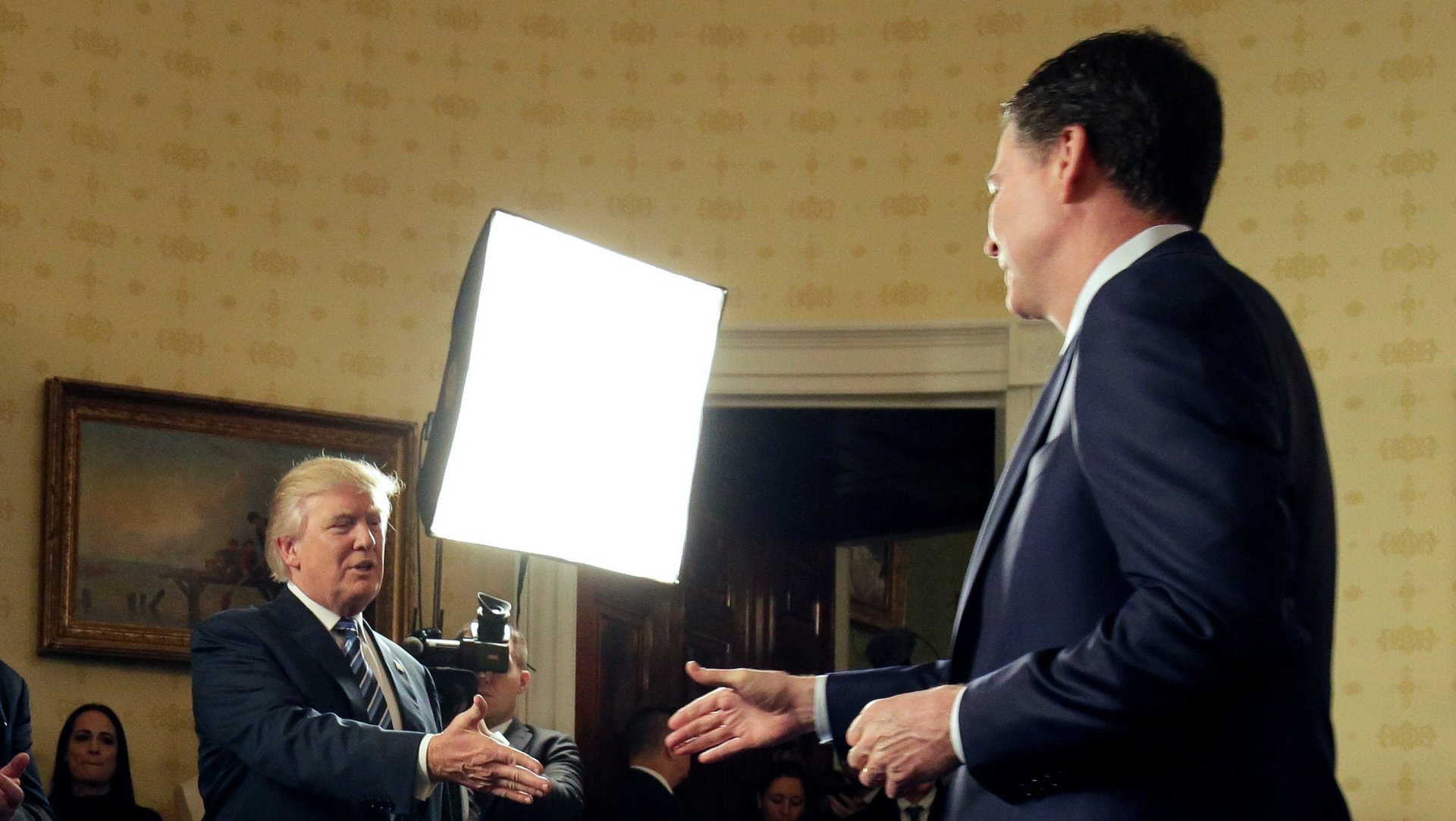

President Donald Trump’s abrupt firing of FBI director James Comey, a decision that some of his very own White House staff didn’t know about until the minute it was announced on TV, has conjured up the inevitable references to one of most infamous constitutional battles in US history: the Watergate scandal.

President Donald Trump’s abrupt firing of FBI director James Comey, a decision that some of his very own White House staff didn’t know about until the minute it was announced on TV, has conjured up the inevitable references to one of most infamous constitutional battles in US history: the Watergate scandal.

News that Trump disclosed classified information—to the Russians of all people—a week after the Comey affair has only added to the sense of despair, shock, and anger in Washington. Members of the national security legal community, attorneys who have served Democratic and Republican presidents, are wondering aloud whether Trump could be removed from office on charges of obstructing his oath. And today, the New York Times has reported that Trump asked Comey directly (paywall) to end his investigation of disgraced NSA director Mike Flynn.

Are we in the beginning stages of a 21st-century version of Watergate? The scandal shook the US political system to its core, but also proved to the entire country that the president of the United States isn’t above the law, no matter how powerful he is.

Trump’s interweaving sagas do have eerie parallels to former president Richard Nixon and Watergate. In 1973, an embattled Nixon was beleaguered by pressure from all quarters in Washington and stories about unethical White House behavior in the front-pages every day. With the inquiry ramping up, he forced his Attorney General, his Deputy Attorney General, and the special Watergate prosecutor out of their jobs in order to obstruct the investigation into the burglary.

Trump, pressured by Democrats on Capitol Hill, multiple congressional investigations into collusion between his campaign and Russia during the 2016 election, and an active FBI inquiry into the matter, hoped the man in Washington directing one of those investigations would drop it, according to a memo obtained by the Times. Comey, when approached by Trump in February, did not agree to drop his investigation of Flynn, and on May 9, Trump fired him.

At the height of Watergate, Nixon was increasingly paranoid, emotionally drained, and isolated from reality. Donald Trump, according to a CNN report, is “increasingly isolated and agitated”—barricaded in the White House, rarely leaving the complex. Trump’s mysterious allusion to secret recordings with the FBI director, and his refusal to discuss it any further, would make the most prolific Nixon biographers and historians wonder whether there is something more to the Watergate comparison than the vague charges of obstruction of justice.

The president’s political enemies are hoping, maybe even praying, that the Trump movie will be a sequel to the Nixon blockbuster: “the Donald,” seeing no other choice but to resign, climbs aboard Marine One, gives a final thumbs up to the television camera, and flies to Mar-a-Lago. Indeed, more and more congressional Democrats are talking about the possibility of launching impeachment proceedings over the Russia matter.

The “I word” is at least within the realm of possibility.

That, however, is where the similarities between the Trump scandal and Watergate come to an end.

After an investigation that lasted over a year and a half, Nixon resigned in the face of an ongoing impeachment process that would have certainly removed him from the job after a Senate conviction. In contrast, Donald Trump is likely immune from the same fate, at least at this point in time. The political realities, the balance of power in Washington, and the extreme difficulty of impeaching a president under the rules codified in the US Constitution all suggest that we should save our breaths and stop talking about Trump’s impeachment and conviction as a realistic prospect.

For one, the Republican Party has demonstrated no interest whatsoever in even beginning discussions—let alone launching—an impeachment probe. Such a move would not only further degrade Trump’s credibility but probably drag the GOP into the muck with him. Lest we forget, the GOP holds all the levers of power in Washington. This means that the Republican majority in the House of Representatives would need to cooperate on some level to make an impeachment proceeding a reality.

Before the House Judiciary Committee could actually get to work, investigate the president for “high crimes and misdemeanors,” and subpoena documents in relation to that investigation, the House of Representatives would have to pass a resolution giving the Judiciary Committee that power (the Watergate impeachment proceedings wouldn’t have happened, for instance, if the House didn’t vote 410-4 to allow the Judiciary Committee to work). Given the current balance of power in the House, Democrats would need at least 23 Republicans to actually authorize an impeachment process—assuming that the intensely partisan House Judiciary Committee would even pass an impeachment resolution in the first place.

Based on present circumstances, that isn’t going to happen. GOP lawmakers aren’t even willing to support a special prosecutor or establish a special congressional committee into a possible Trump-Russia connection. It’s inconceivable that they would throw an assist to Trump’s political opponents by starting an unpredictable process that could possibly overthrow a Republican president.

But let’s assume that more sensitive information comes out that is damaging to the president. Let’s assume, for the purposes of this exercise, that FBI or the Senate Intelligence Committee investigators come across evidence that senior staffers in Trump’s campaign—but not Trump himself—partnered in some way with Russian intelligence operatives to hurt Hillary Clinton’s campaign. And let’s assume that an increasing number of lawmakers in the GOP caucus become convinced that Trump either knew about it and didn’t stop it, or perhaps authorized it. That would be grounds for impeachment, right?

It’s certainly possible. As former congressman and president Gerald Ford famously said, “[a]n impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.” Indeed, if evidence came to light that was this explosive, at least some Republicans in Congress would be hard pressed to keep laying their personal reputations on the line in order to defend a president who is perceived to have engaged in illegal acts.

The big problem with impeachment that gets overlooked—and to which Democrats broaching the subject are choosing to ignore—is that it’s a Herculean task. To state the obvious: it’s enormously difficult to remove a US president from office. The political winds in Washington, the nature of the crime or crimes being investigated, and the high threshold in the Senate for convicting the president for those crime have to be in perfect alignment for Congress to strip the president’s power away. And this doesn’t even take into account the mini-debates in the Senate about how the trial should be conducted, how many witnesses to call, how much discretion House managers (the prosecution team) will be afforded, and whether the Senate debate should take place in public or private session. All of these questions elongated the Senate trial of president Bill Clinton, and it tore the Republican Party apart, dividing firebrand House conservatives from more cautious senators who wanted the entire affair done and over with. In the end, the trial concluded with Clinton beating the charges.

The founders of the Constitution set a very high bar for conviction: two-thirds of the Senate, or 67 votes. If a political party doesn’t have an astronomically large majority in the 100-seat chamber (something that hasn’t happened since the 89th Congress over a half-century ago), Republicans and Democrats need to be persuaded that high crimes were committed. Charging and removing a president can’t be a purely partisan exercise.

In the Senate, as its membership is composed today, this bipartisanship would mean that 14 Republicans would have to join all of the chamber’s Democrats to kick Trump out of office. Does anyone really believe that over a quarter of the Senate Republican caucus would kick out a Republican president?

The bottom line: until some smoking gun recordings of Trump come out into the public domain, or some new documentary evidence is released that is so serious, and so contrary to the rule of law that even Republicans find it in their interest to distance themselves from the White House, we should all stop talking about impeachment. It may be an interesting academic and legal discussion, and it’s perfect fodder for cable news broadcasts. But the political atmosphere in Washington will have to undergo a massive change in equilibrium for the impeachment process to be anything more than a dream.