Ringling Bros. is closing for good. A backstage look at the end of the “Greatest Show on Earth”

After almost a century and a half, the “Greatest Show on Earth” is coming to an end. Associated Press reporters tagged along with the Ringling Bros. Circus in its final days to witness the lives of circus performers, who live and travel across the United States by train, together with animals of the circus.

After almost a century and a half, the “Greatest Show on Earth” is coming to an end. Associated Press reporters tagged along with the Ringling Bros. Circus in its final days to witness the lives of circus performers, who live and travel across the United States by train, together with animals of the circus.

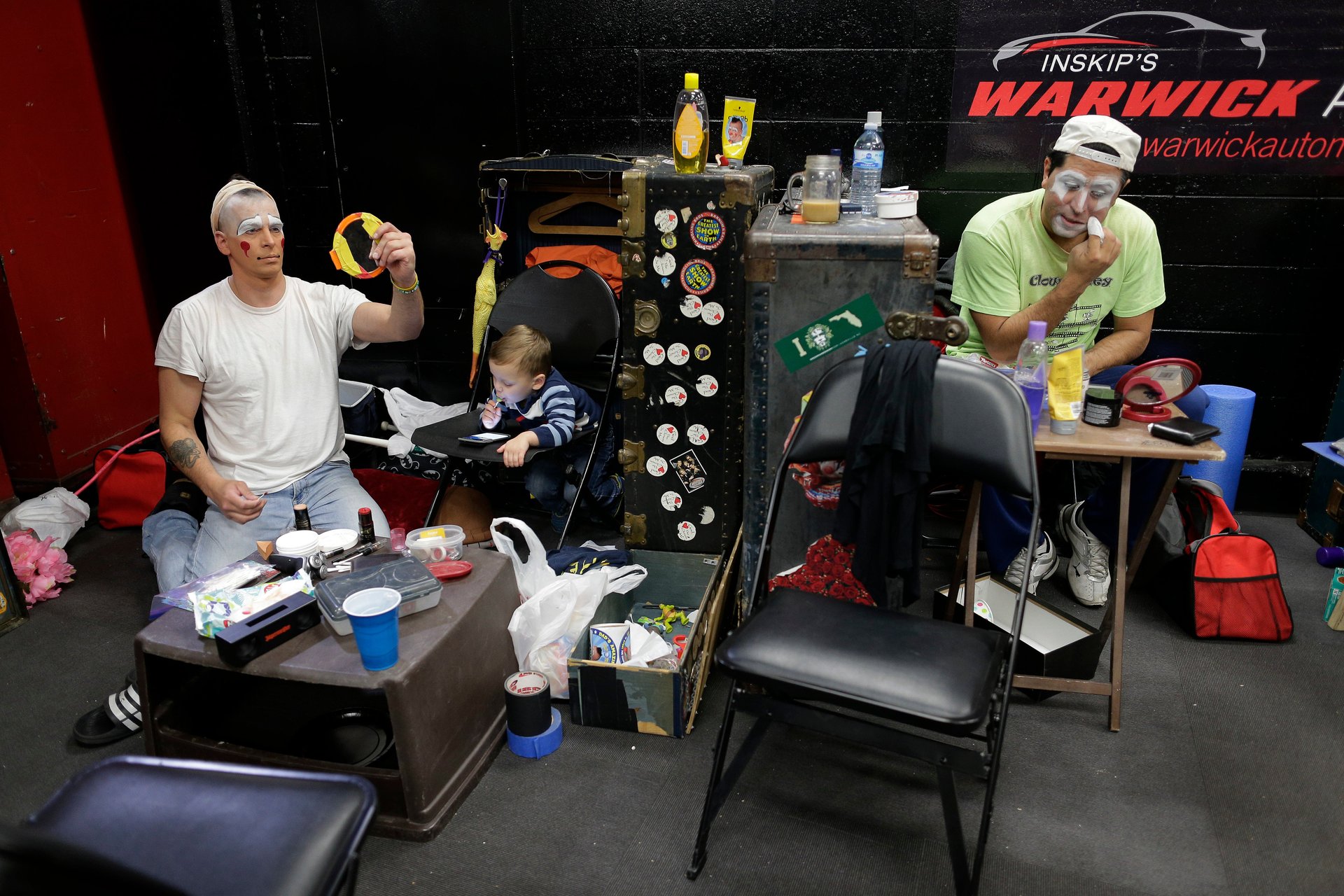

Backstage, performers prepare for shows and apply their make up. On the mile-long train slowly chugging between towns and cities, they socialize in the “Pie Car,” nurse their newborns, and write personal diaries. Occasionally, a toddler is baptized by a reverend from the Circus and Traveling Shows Ministry of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops. (Yes, there is a ministry.)

But some train parts have been auctioned off, and a few performers have bought new homes in Las Vegas, where they will continue their careers after the circus shuts down. Animals have found new homes in sanctuaries.

Founded in the late 1800s in Wisconsin, Ringling Bros., now owned by Feld Entertainment, has seen its ticket sales slump in recent years. It has long been attacked for alleged animal abuse. One such allegation led to a 14-year legal battle with animal-rights groups, who, it turned out, had bribed a former circus producer nearly $200,000 to make false accusations about the circus’s treatment of animals. The groups ended up paying Feld a total of some $25 million in settlement costs.

But even after Ringling Bros announced in 2015 that it would phase out its herd of elephants, it couldn’t stem the decline. It seems that the audience’s taste has moved on from the kind of circus act that many grew up watching.