In defense of hunky heartthrobs, and the women who love them

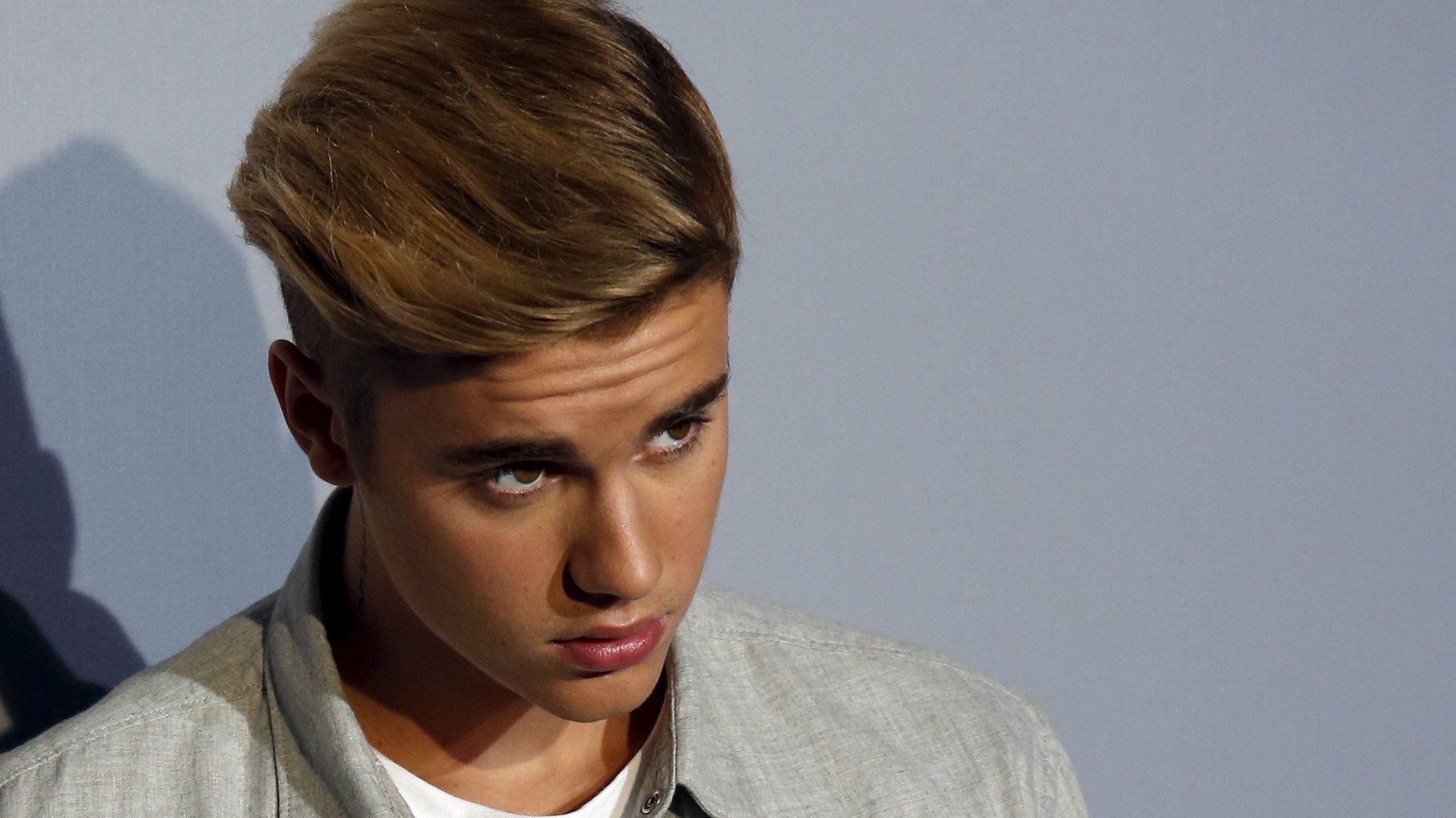

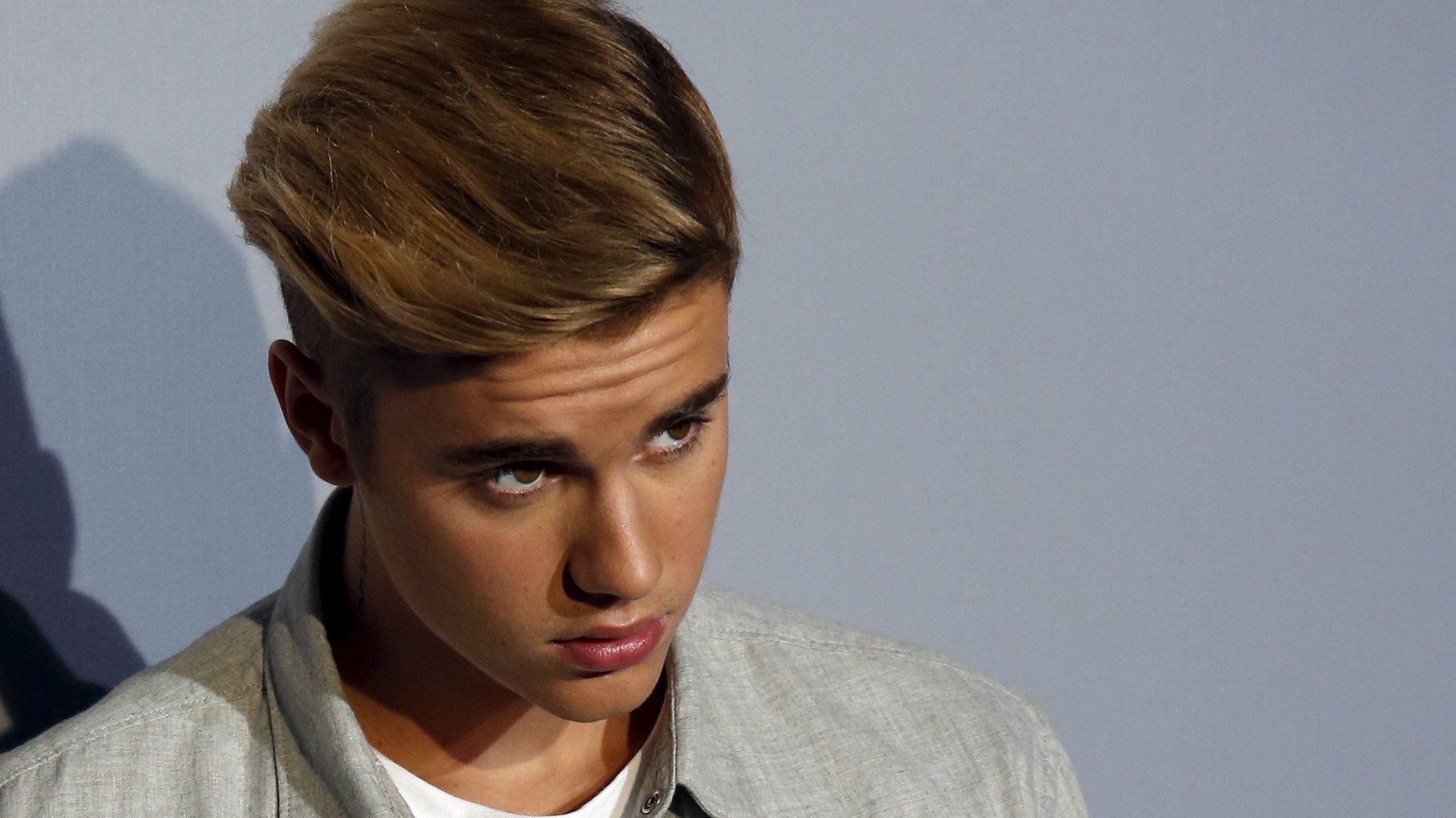

When men say they’re attracted to Margot Robbie or Scarlett Johansson, nobody bats an eye. But when women want to look at pretty guys, people tend to get nervous. The Wall Street Journal once described fan reaction to Justin Bieber as a “disease” which is “highly contagious and can affect mothers too.” Robert Pattison, star of the Twilight franchise, said himself that the Twilight fandom had become “a bit of a cult. People like being part of the club. They’re obsessed.”

When men say they’re attracted to Margot Robbie or Scarlett Johansson, nobody bats an eye. But when women want to look at pretty guys, people tend to get nervous. The Wall Street Journal once described fan reaction to Justin Bieber as a “disease” which is “highly contagious and can affect mothers too.” Robert Pattison, star of the Twilight franchise, said himself that the Twilight fandom had become “a bit of a cult. People like being part of the club. They’re obsessed.”

These comments are tongue-in-cheek, but they’re also indicative of a sexual double standard. As Carol Dyhouse writes in her new book Heartthrobs: A History of Women and Desire, in patriarchal cultures, men are supposed to be the ones doing the lusting. Female desire upsets the natural order of things. “Think of the Maenads of Greek myth dolled up in fawn-skins, intoxicated, brandishing their thyrses (long sticks wreathed in ivy and tipped with pinecones),” Dyhouse told me by email. “The Maenads were unstoppable, out of control.” When they set their sights on Orpheus, one of the first pop stars, they literally tore him apart.

The Maenads in their own time were a misogynist fever dream—and disdain for female desire is still evident in our attitudes toward the hunks of today. And so Dyhouse’s book urges us to re-examine mainstream culture’s tendency to dismiss heartthrobs and the women who love them.

If desiring women provoke cultural anxiety, so do the men who emerge as objects of desire. Heartthrobs ranging from early film actor Rudolph Valentino all the way on through Bieber and Pattison have been viewed with suspicion by their fellow men. They’re too pretty, too conscious of their looks—too associated with women. In other words, the resistance to heartthrobs often carries a tinge of homophobia. Valentino, Dyhouse says, “was very graceful, olive-skinned, sensitive” and was “derided as a ‘Ladies’ man,” which was a term used as “shorthand for men who guys might feel uneasy with in the locker room.” Dyhouse points out that in the 1950s, men considered too close to their mothers, like Elvis and the massive heartthrob Liberace, were often called “sissies.”

No doubt some of the dislike that heartthrobs provoke in men can be chalked up to jealousy. Fictional heartthrobs are often wealthy, powerful, sensitive and mysterious, from Jane Austen’s Mr. Darcy to Valentino’s Sheik (1921) to 50 Shades of Grey’s Christian Grey. Men who are not billionaires with dark secrets or sparkly vampires driving luxury cars may feel a bit inadequate in comparison.

But the dislike of heartthrobs is also tinged with homophobia. Heartthrobs typically appear in movies, TV shows, concerts, and magazines that cater to a female audience, making them the center of a desiring gaze. And so men watching The Sheik or reading Twilight become nervous when they expose themselves to material meant to appeal to straight women and their libidos. Watch a movie that frames a guy as the object of sexual desire, and who knows who you’ll end up wanting?

Heartthrobs are disturbing because they make men question their own manliness. “When Marie Stopes wrote about female sexual desire in Married Love (1918) she attracted a great deal of vituperation,” Dyhouse told me. “One English aristocrat accused her of fomenting unrest, encouraging wives to think of themselves as frustrated and rearing a race of demanding, vampire women.” Women who do the desiring are implicitly masculine or monstrous, rendering men weak and girlish in comparison.

Women’s sexual fantasies are often criticized as regressive. Everybody with access to keyboard attacked both Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey for idealizing female dependence and blandly reworking the story of passive Cinderella whisked away by a wealthy prince. But, Dyhouse told me that those Cinderella stories are more complicated than they look.

“I think you can say that narratives of romance are often about women figuring out how to live with patriarchy, but wanting, at the same time, to transform it, or at least to soften it at the edges,” she says. In Pride and Prejudice, Lizzy moves up in social status through marrying the rich and powerful Mr. Darcy, which is one way patriarchy works. But it isn’t just Lizzy who is changed, Dyhouse notes. ” She’s also somehow transformed him from an insufferable snob into a decent, caring guy.”

Literary critic John Carey said he’d never met a man who liked Darcy, and Heartthrobs mentions several other notable literary men who say Darcy was not for them. Darcy is a fantasy for women, and men dislike him precisely because he gets transformed in accordance with Lizzy’s wishes. Heartthrobs suggest that men may need to alter themselves, and their patriarchal systems, to cater to female desires—and that makes them dangerous.

This isn’t to say that every pre-teen girl who tore a picture of Jonathan Taylor Thomas out of Teen Beat was making a conscious political choice. But the first step toward political change is starting to desire it. And so, Dyhouse suggests that pining after heartthrobs is—or can be—a way for women to start demanding more from patriarchy and from men. Today Bieber fever; tomorrow the world.