In defense of amateurs

“If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.”

“If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.”

So goes one of the G.K. Chesterton’s most famous and most quoted lines.

Considered “a man of colossal genius” by George Bernard Shaw, G.K. Chesterton was a prolific writer— publishing 80 books, 200 short stories, and over 4,000 essays in his lifetime.

And in those prolific writings, Chesterton gave special meaning to the amateur over the professional, to the generalist over the specialist.

Why? Isn’t being a professional a good thing?

Not always.

What happened to the amateur?

Inspiration is for amateurs—the rest of us just show up and get to work.

—Chuck Close

The word amateur doesn’t get a lot of love these days. When we hear “amateur,” we think of a dabbler—someone unskilled and undisciplined who flutters from one hobby to another.

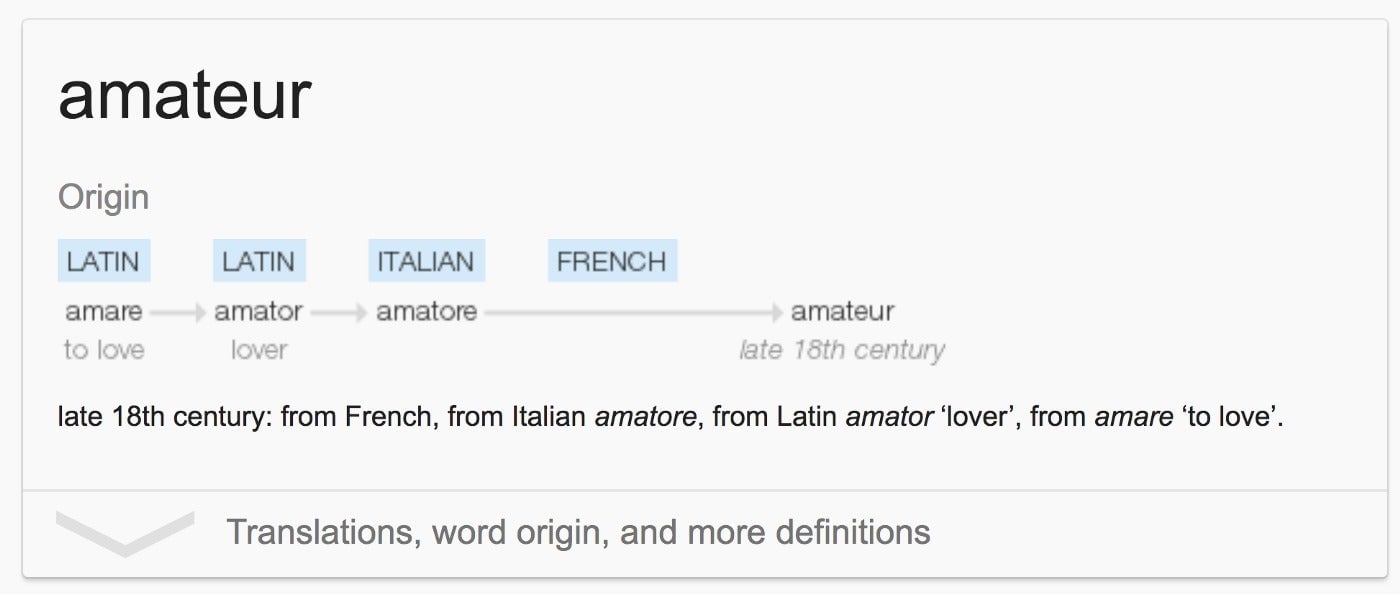

The word amateur used to have a different meaning, though. A quick search for the “amateur etymology” shows the word’s origins:

Originally, to be an amateur simply meant to love something.

Chesterton says as much in his biography of Robert Browning:

The word amateur has come by the thousand oddities of language to convey an idea of tepidity; whereas the word itself has the meaning of passion. Nor is this peculiarity confined to the mere form of the word; the actual characteristic of these nameless dilettanti is a genuine fire and reality. A man must love a thing very much if he not only practices it without any hope of fame or money, but even practices it without any hope of doing it well. Such a man must love the toils of the work more than any other man can love the rewards of it.

Growing up, Chesterton was inspired by his father, whose “profession” was that of a real estate agent but spent much of his private life exploring drawing, painting, photography, magic lanterns, and the like.

In his Autobiography, Chesterton writes of his father:

To us (children) he appeared to be indeed The Man with the Golden Key, the magician opening the gates of goblin castles . . . but all this time he was known to the world, and even to the next door neighbors, as a very reliable and capable, though rather unambitious businessman. It was a very good lesson in what is also the last lesson in life: that in everything that matters, the inside is much larger than the outside. On the whole, I am glad that he was never a professional artist. It might have stood in his way of becoming an amateur. It might have spoilt his career—his private career.

Wait, what?

What does Chesterton mean when he says that being a professional can stand in the way of “becoming an amateur?” The answer, I think, lies in what Chesterton calls the amateur’s “genuine fire and reality.”

To understand this, let us introduce Dr. Xu—a hypothetical (but professional) plastic surgeon. Dr. Xu’s full title is “Dr. Winston Xu, MD, PhD”—no doubt signaling his great proficiency at the wise art of facial reconstruction.

Dr. Xu may indeed be very good at what he does. However, no matter how good Dr. Xu is, there is always something to worry about—does Dr. Xu truly have the best interests of his patient in mind? Perhaps the only thing in Dr. Xu’s mind is next week’s paycheck, or a snide compliment he got last week from Dr. Lee (his rival), or simply the dinner awaiting him at home.

Here lies the problem.

While a professional has many reasons for doing something (money, prestige, power), an amateur has only one —the “genuine fire and reality” of pure, unbridled passion.

You can always trust an amateur.

Alive and well

In an age of increasing complexity, it is true that jobs are becoming more and more specialized. By the time a student exits the system as an “expert,” she may have been in school for over 20 years.

But saying that professions are becoming more specialized is NOT the same as saying that there is no room for amateurs. And it certainly does not mean amateurs cannot contribute.

Take the tech industry, for example.

Google, Microsoft, Facebook—all of these big companies were started by amateurs. And then there’s Wikipedia, which, despite being run (almost) entirely by amateurs, has replaced the eminent and professional Encyclopaedia Brittanica.

The internet has shown us there are people willing to make things with no immediate benefit at all. And they do pretty damn good job of it.

The amateur is back.

Paul Graham, multi-millionaire and founder of startup incubator Y Combinator comments on the return of the amateur in an essay (Graham’s “amateur” essays have been read millions of times):

I suspect professionalism was always overrated … I think [it] was largely a fashion, driven by conditions that happened to exist in the twentieth century.

The main conditions, argues Graham, were narrow “channels” that prevented amateurs from competing:

It was the narrowness of such channels that made professionals seem so superior to amateurs. There were only a few jobs as professional journalists, for example, so competition ensured the average journalist was fairly good. Whereas anyone can express opinions about current events in a bar. And so the average person expressing his opinions in a bar sounds like an idiot compared to a journalist writing about the subject.

The average person, sure, can’t match up to a journalist. Choose a random blog on the internet—chances are that the writing is poor.

That, says Graham, is missing the point:

Those in the print media who dismiss the writing online because of its low average quality are missing an important point: no one reads the average blog. In the old world of channels, it meant something to talk about average quality, because that’s what you were getting whether you liked it or not.

But now you can read any writer you want. So the average quality of writing online isn’t what the print media are competing against. They’re competing against the best writing online. And, like Microsoft, they’re losing.

Who’da thunk it?

When you love something so much that you’d do it without pay, you can end up pretty good at it. So good that, at times, that you might outclass the professionals.

We are all amateurs

Now, let us return to Chesterton’s quote: “If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.”

To understand what Chesterton means here, let us turn to the writing of Simon Leys (the pen-name of Pierre Ryckmans)—sinologist, essayist, and ex-professor at the University of Sydney.

In an essay on Chesterton in The Halls of Uselessness: Collected Essays, Leys points out that, for some things, professionalism is an impossibility:

Think of it: you can, and should, be fully professional insomuch as you happen to be a real estate agent, a solicitor, a grave-digger, an accountant, a dentist, etc.—but you could hardly call yourself a professional poet, for instance. If, on a passport or an immigration form, you were to write under “Occupation” the words “Human being” or “Living,” the bureaucrat behind his counter would probably wonder if you were in your right mind.

None of the activities that really matter can be pursued in a merely professional capacity; for instance, the emergence of the professional politician marks the decline of democracy, since in a true democracy politics should be the privilege and duty of every citizen. When love becomes professional, it is prostitution. You need to provide evidence of professional training even to obtain the modest position of street-sweeper or dog-catcher, but no one questions your competence when you wish to become a husband or a wife, a father or a mother—and yet these are full-time occupations of supreme importance, which actually require talents bordering on genius.

The things worth doing are worth doing always—whether we do them “badly” or not.

This post originally appeared at Better Humans.