Why Americans must stop talking about Trump’s mythical “white working class” voters

Ever since Donald Trump won the US presidential election back in November, the media has focused its attention on one group of Americans: the white working class. It seems like every week, there is a new thinkpiece debating what to do with the white working class, especially since it seems many of them who voted for Trump now have buyer’s remorse. Given the apparent role these voters played in putting Trump in power, this may seem like a worthwhile discussion to have. But in reality, this focus on the white working class is leading to a toxic and unproductive conversation on inequality.

Ever since Donald Trump won the US presidential election back in November, the media has focused its attention on one group of Americans: the white working class. It seems like every week, there is a new thinkpiece debating what to do with the white working class, especially since it seems many of them who voted for Trump now have buyer’s remorse. Given the apparent role these voters played in putting Trump in power, this may seem like a worthwhile discussion to have. But in reality, this focus on the white working class is leading to a toxic and unproductive conversation on inequality.

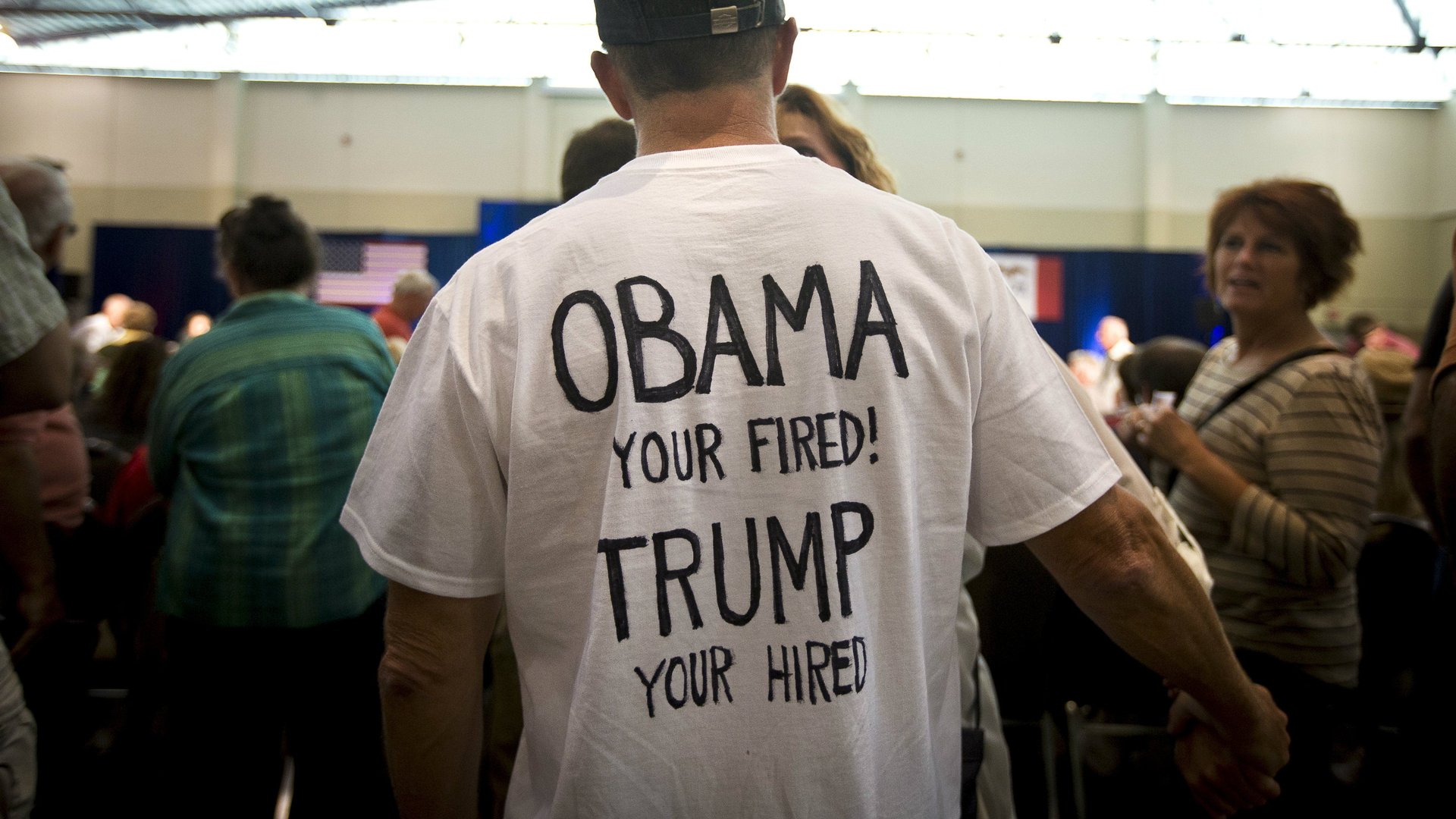

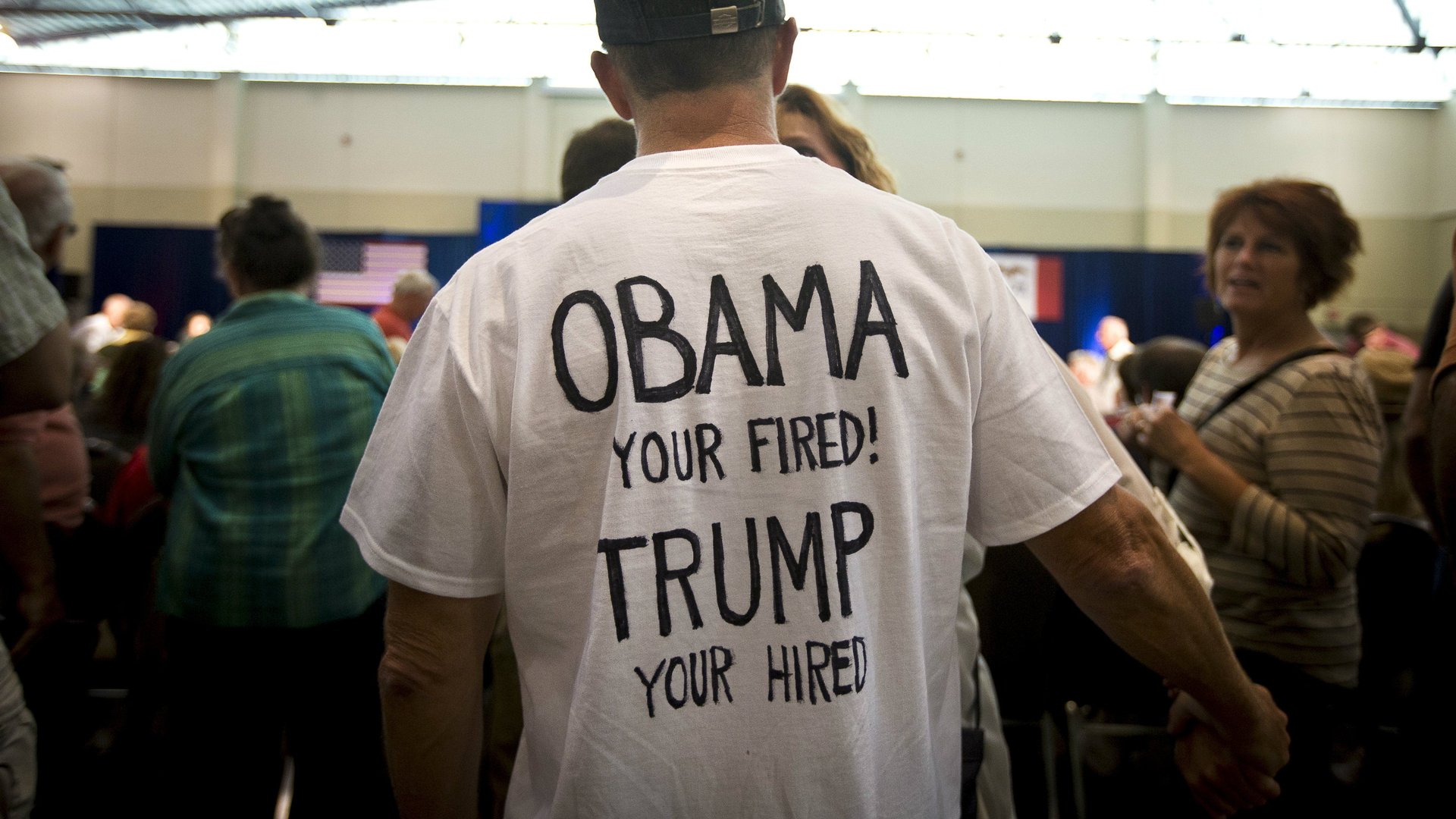

During the campaign, the public was bombarded with images of raucous Trump supporters at his rallies—white, middle aged, men (and women) wearing “Make America Great Again” hats gathered in auditoriums, chanting “lock her up” and physically harassing and intimidating protestors. These supporters were made out to be working-class voices from Middle America, expressing “economic anxiety” in the form of racist comments. So was born the myth that Trump supporters were all working-class white people.

A look at the demographic data from election night tells a different story; white people, of all ages, education statuses, and genders voted for Trump. While it is true that out-of-work coal miners from West Virginia cast ballots for Trump, so too did the affluent in cozy suburbs. The assumption that Trump voters are working class is born out of a classist assumption that assigns racist behavior to “poor white” people, rather than being a systemic issue with all white people. White working-class people were not solely responsible for Trump—white people as a whole were.

Still though, this myth continues to pervade in the news media and affects how issues are covered. For example, during the health care debate, news outlets have run stories about how Trump supporters are just now realizing that they may lose health insurance. Just recently, a woman was in the news because she voted for Trump, not realizing his policies would lead to her undocumented husband’s deportation. These stories make for good clickbait that elicit a predictable reaction: these people deserve this hardship because they voted for it.

It goes without saying that nobody deserves to suffer based on who they vote for, but it is hard for some to have empathy for these people, particularly when black and brown communities are not afforded the same privilege. This type of media coverage is a distraction that shifts our attention away from the issues. There were plenty of people who were poised to lose health insurance who did not vote for Trump, and most people affected by deportations are not white Trump voters. Coverage of working-class white Trump voters could have just as easily focused on his backers on Wall Street or his upper-middle-class supporters.

This linking of the white working class to Donald Trump also creates a needless dichotomy between class and identity issues, making it seem as if addressing economic inequality means pandering to a group of racist voters. But issues of race and class are interlinked, as organizers of color recognize. Just a few weeks ago, Fight for 15 and Black Lives Matter organized a national day of action to call attention to the issue of income inequality, specifically in black and brown communities. In fact, people of color will make up the majority of the American working class come 2030, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

There are other issues with the focus on the white working class as well. Talking about the white working class as a disenfranchised and suffering group might imply that their whiteness is the reason why they were left behind. In a time when talk of reparations and targeted programs for people of color are called “reverse racism,” this is a problematic way to frame white poverty. In fact, many of the factors that have hurt white working-class people, like deindustrialization, have also hurt communities of color; the most notable example being Flint, Michigan.

The white working class is a group that makes up almost half of the country, is geographically spread out, and encompasses people working all sorts of jobs. But the way we talk about the white working class does not capture this—instead, stereotypical narratives of ignorant white people living in Appalachia prevail. It would make much more sense to talk about what issues workers in different regions and communities are facing, rather than relying on this mythological imagining of white people in “Middle America.”

To be clear, there are real issues with white working-class communities in the US, and people are suffering. But the current discourse does not accurately address this.

We can do better by centering our discussion on the issues that are making the lives of working-class people—both people of color and white people—difficult. Ensuring that everyone has health care, can go to college, or earns a living wage won’t cure poor white people of racism. But it will make the lives of all Americans better. We need to end this obsession with this one group, lest it compromise our ability to stay focused and make progress on issues of inequality.