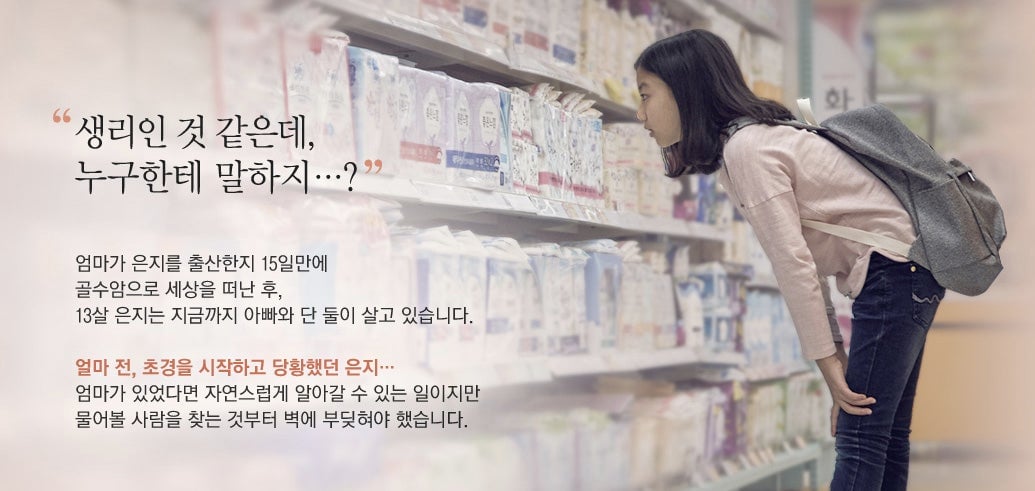

An outcry over DIY period pads has sparked a national menstruation conversation in Korea

Eun-seo, a 16-year-old girl who lives only with her disabled father, cannot afford sanitary napkins and with no proper education at home about how to handle her periods, wraps tissues around shoe insoles instead to make her own pads. She once bled for three weeks straight, only to find out later she had a 20-centimeter lump on her uterus.

Eun-seo, a 16-year-old girl who lives only with her disabled father, cannot afford sanitary napkins and with no proper education at home about how to handle her periods, wraps tissues around shoe insoles instead to make her own pads. She once bled for three weeks straight, only to find out later she had a 20-centimeter lump on her uterus.

She isn’t alone in South Korea. According to Good Neighbors, a Korean charity which published Eun-seo’s account (link in Korean) last year, there are tens of thousands of girls in the same situation as Eun-seo (not her real name) of being unable to afford proper menstrual products.

News of the “insole girls” exploded in Korean social media last summer after media reports said that Yuhan-Kimberly, the dominant maker of sanitary products in the country, raised prices of its pads by 20%—even though pad prices in Korea were already among the highest in the region. A public discussion has kept going since then, breaking down long-standing taboos in Korea around talking about the issue.

”Because of the ‘insoles pad’ news, it is now easier to talk in public about sanitary pads. Young women in Korea now see that talking about it is not something embarrassing,” said Boo So-yun, 21, a student at Ewha Womans University in Seoul who also complained that the price of pads in Korea is “ridiculously high.”

An expensive place to have a period

During the recent presidential campaign that followed the parliamentary impeachment of former president Park Geun-hye, even a male politician weighed in on the issue.

“Sanitary pads should be treated as public goods,” said Lee Jae-myung (link in Korean), a city mayor, speaking ahead of a party primary in January. “The insole pads expose the truth of poor social welfare in Korea… Our culture sees menstruation as something to be embarrassed about and something that is unclean, preventing the issue of the price of sanitary pads to come under the spotlight.” (Lee lost the party primary to Moon Jae-in, who won the presidency last month.)

A pack of 10 pads from Yuhan-Kimberly costs about $2.53, according to prices on Gmarket, Korea’s biggest ecommerce site. That means a month’s supply would run a little above $5—nearly equivalent to an hour’s work at Korea’s minimum wage. For comparison, 10 pads of the cheapest Always pads, a dominant brand in the US, are approximately $1.80 on Walmart’s website, while the US federal minimum hourly wage is $7.25.

As the stories of girls using insoles as pads spread around Korea’s internet, anger mounted. Media reports said that the cost of one Yuhan-Kimberly “White New Secret Hole” 36-pack of pads had become 9,631 won ($8.6), a 42.4% increase from a year earlier. According to the Korea National Council of Consumer Organizations, the price hikes came despite the fact that the price of pulp, a major component, had actually fallen.

A representative of Yuhan-Kimberly told Quartz that the company did not raise its prices last year, and that the prices are determined by the vendors.

In a statement (link in Korean) last summer, Yuhan-Kimberly pledged to donate 1.5 million pads and develop cheaper products.

“Yuhan-Kimberly understands that there are some teenagers who have difficulties purchasing pads. We are very sorry to hear this,” said the company at the time.

Good Neighbors, the charity, said that it has an ongoing campaign called “Girl, you are a shining star” to help underprivileged girls in Korea with their menstruation needs. This year, they plan to distribute a present box to 2,000 girls with six months worth of pads, coupons for underwear, and cosmetics. The charity will also provide counseling services to girls and their families, such as teens who live with grandparents or a single parent who is unable to help them with their physical needs.

Korea exports menstrual cups—but they can’t be sold in the country

The discussion over the insole girls has also sparked interest in alternative and more cost-effective products, such as menstrual cups—but Korean law has so far kept them out of reach.

Like many other countries in Asia, tampons remain largely unknown or unpopular. According to a survey (link in Korean) by Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety released in May, some 81% of women use sanitary napkins, and 11% use tampons. A survey by the Center for Disease Control in the US conducted in 2015 found that 62% of women use pads and 42% use tampons (the results include women who use both).

Alternatives like cups and reusable pads are used by a small minority in the US, favored by a few mainly for their eco-friendly credentials. Now some women’s groups are trying to introduce cups—silicone or latex inserts that catch the flow—to Korea, but have run into hurdles.

In March, Korean customs stopped a women’s group from bringing 500 menstruation cups into Korea from France. A customs official told local media that because the items are to be inserted into people’s bodies they need to be tested for safety. One Korean manufacturer of a range of silicon-based products already produces menstrual cups in Korea, but only for overseas markets—its Unicup received FDA approval (link in Korean) in the US in April.

The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety said in May (link in Korean) that it will approve menstrual cups to be legally imported or domestically produced some time this summer.

This month, though, the chairman of the Korean Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Kim Dong-seok, has said that menstrual cups aren’t proven to be safe. “Blood can clot inside the body. If there is an infection, women can have septicemia,” Kim told Korea’s Chosun Ilbo newspaper (link in Korean). “We cannot be sure about the side effects because there has not been enough clinical research.”

Advocates of menstrual cups say that the products carry a lower chance of toxic shock syndrome, a bacterial infection, than tampons. Elsewhere in Asia, Taiwan recently approved the sale of menstrual cups following a crowdfunding campaign to produce a cup in Taiwan, and an online petition demanding the government legalize the sale of cups. In Japan, the government last year approved (link in Japanese) the domestic sale of the SckoonCup.

Menstrual cup chat rooms

As the Korean goverment makes up its mind, companies are already vying to produce menstruation cups domestically, including EaseandMore, which sells feminine products (link in Korean) online such as warm packs for period pains, cleansing wipes, Thinx underwear, and gift boxes for girls who have just started their periods. It also makes donations of its products.

EaseandMore has also been hosting “menstrual cup chats” where women asked questions such as how to clean the cups in a public bathroom.

Women pay 5,000 won to attend the events, where they discuss the pros and cons of different makes of menstrual cups. In April, the company launched a crowdfunding campaign (link in Korean) called the Blank Cup Project (link in Korean), raising 59 million won ($53,000) with the explicit aim of producing the first menstruation cup in Korea that would secure government approval.

“There are very few choices for Korean women for dealing with menstruation and little information out there about new products like cups,” said Ahn Ji-hye, a representative of EaseandMore. ”Donating pads is just a temporary measure.”