An island doomed by rising seas helped the US show it can thwart long-range North Korean missiles

Donald Trump has called climate change a hoax. He might want to check with US military experts about that.

Donald Trump has called climate change a hoax. He might want to check with US military experts about that.

In September 2016, a group of retired generals and admirals from all branches of service released a report concluding that “sea level rise risks to coastal military installations will present serious risks to military readiness, operations and strategy.” The report notes that (pdf, p. 5) the capability of American forces…

“…rests on an assumption of climate stability—including the stability of the 95,471 miles of coastline along which 1,774 U.S. military sites reside across the globe. In the 21st century, the stability of that climate, and the stability of those coastlines from which the military launches its operations, is set to change dramatically due to sea level rise and storm surge.”

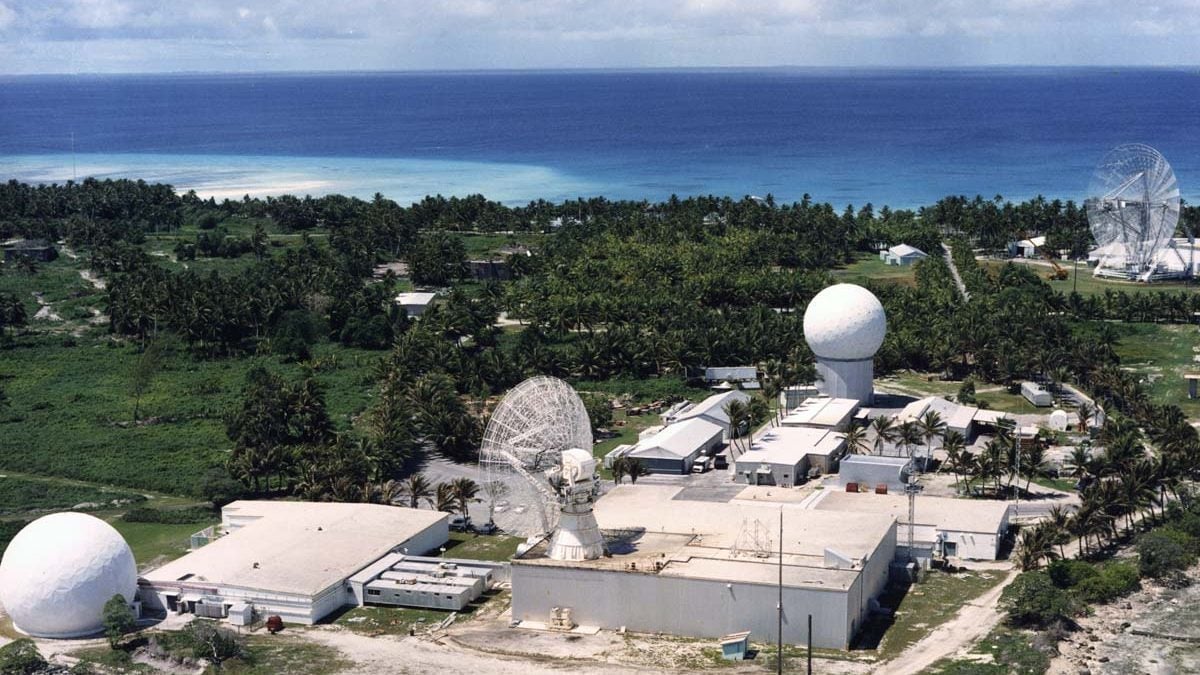

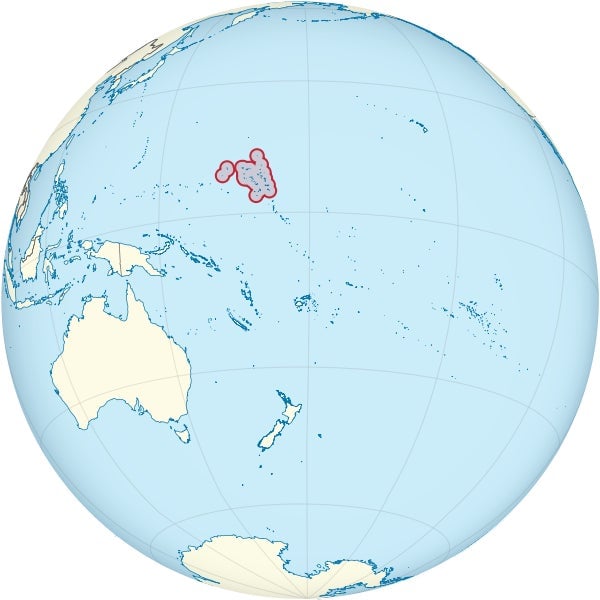

Published by the Center for Climate & Security, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, DC, the report commits a section (p. 31) to the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean, focusing on the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site in the Kwajalein Atoll. It describes the site as a key asset “for testing missiles and missile interceptors and conducting work for US Strategic Command, NASA, and others.” But, it notes, “The Marshall Islands are seeing increasingly intense impacts of storms and sea level rise, both exacerbated by the warming of the planet.”

The site recently played a key role in testing the US’s ability to thwart an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) heading from North Korea (or other countries) to the American mainland. In the first test of its kind, the military launched a mock ICBM from Kwajalein toward waters just south of Alaska, and an interceptor missile fired from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California took it out. North Korea is working toward the ability to hit US cities with nuclear ICBMs.

The successful test gave a much-needed credibility boost to the Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, rushed into existence in 2002 by George W. Bush. The Union of Concerned Scientists heavily criticized the program last year, saying it had resulted in “expensive purchases of unproven technologies, major schedule and cost overruns, an abysmal test record, and, nearly fifteen years later, no proven capability to protect the United States.” Even with the successful test, many still harbor strong doubts about the system.

But few doubt the importance of Kwajalein in testing and improving such systems. (Elon Musk’s SpaceX has launched Falcon 1 rockets from there as well.) The US Army describes the Reagan test site (pdf, p. 3) as “a multi-billion dollar facility with state-of-the-art instrumentation unmatched anywhere in the world. It offers space tracking and full-envelope strategic and tactical missile testing with the world’s most sophisticated suite of radar, optics, telemetry and scoring sensors.”

Those sensors will do little good if the land below them disappears, which is what many scientists think will happen to much of the Marshall Islands. Flooding is already hitting the islands hard. In 2008, Kwajalein Island–the largest in the atoll and home to the test site—was hit by tidal wash flooding that ruined freshwater supplies. The military responded with (paywall) heavy-duty sea walls and pricey desalination machines.

An article in Hakai Magazine noted:

The 2008 flood was intense, but many wrote it off as a… freak event, the kind of natural disaster that visits the region every few decades.

Except that the following year, in 2009, it happened again. And again. “Inundation events,” as they’re now euphemistically known, are no longer once-in-a-lifetime occasions. For the past few years, they’ve swamped vulnerable neighborhoods at least biannually and sometimes even more frequently, usually during the highest tides of the year.

The publication interviewed Mark Stege, executive director of the Marshall Islands Conservation Society, noting he “feels certain there will come a time when the Marshall Islands are no longer habitable. There won’t be a sudden exodus, a single moment, but over years or even decades, people will reach their personal threshold and leave.”

For the 11 islands it uses in the Kwajalein Atoll, the US military has a lease lasting until 2066. It could be forced to leave sooner by the rising sea.