Nigeria needs to start talking about the horrors of the Biafra war, fifty years on

In 2014, the Nigerian National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) flagged the widely publicized film adaptation of Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s bestselling novel, “Half of a Yellow Sun” to ensure that it would not undermine national security. While people around the world watched the film, in Nigeria, its release had been delayed. The film tells the story of two sisters trying to stay alive during the 1967-1970 Nigeria-Biafra War.

In 2014, the Nigerian National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) flagged the widely publicized film adaptation of Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s bestselling novel, “Half of a Yellow Sun” to ensure that it would not undermine national security. While people around the world watched the film, in Nigeria, its release had been delayed. The film tells the story of two sisters trying to stay alive during the 1967-1970 Nigeria-Biafra War.

Nigeria’s civil war is such a sensitive topic in the country, that the government has never given an official death toll. Quoted figures range from one million to as high as six million.

“One of the reasons Nigeria is more divided today than it was before the war started is because we have refused to talk about the elephant in the room,” the film director, Biyi Bandele told the BBC.

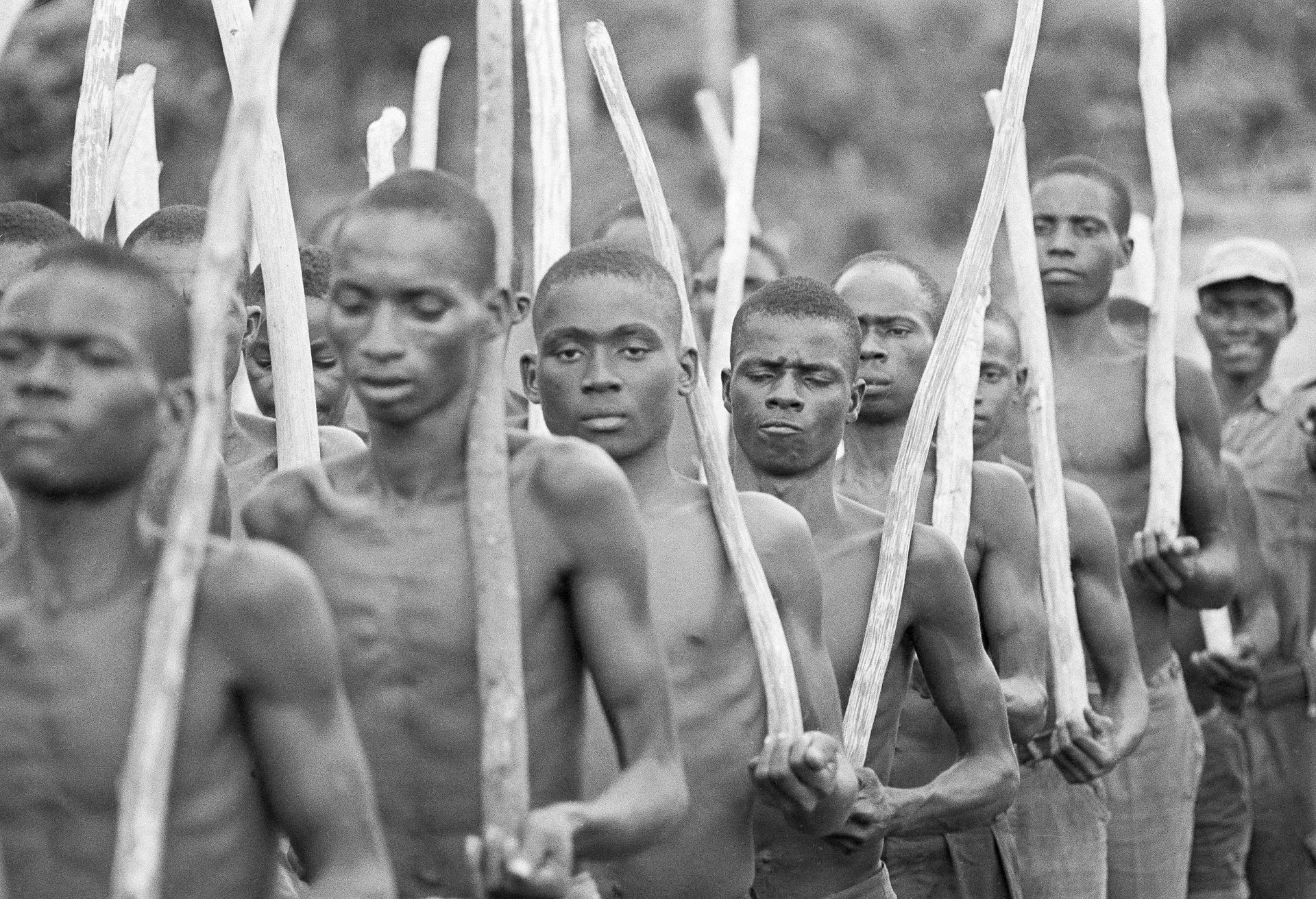

The southeast region’s leaders, citing grievances including a pogrom of Igbo people by locals in northern Nigeria, declared independence on May 30 1967 to form the Republic of Biafra. But the Nigerian government of the day resisted the break-up of the country that was created by the British in 1914.

On paper, the war ended in 1970. But in 2017, Nigeria is still grappling with the aftermath.

If you visit Okigwe, a city in Imo state, and ask the locals where the Biafran War Veterans Camp is, they’ll point towards a clearing off a long pebbled dirt road beyond a bridge that runs over a creek. There, you’ll meet war veterans in wheelchairs and on crutches. They stumble around with post-traumatic stress disorder, trying to carry on with the mundane tasks of life- taking a bath or putting on their shoes- as graphic images of what they saw during the war flash into their consciousness every so often.

The men there live in obscurity. One by one, they’re dying, without writing memoirs. As they die, history goes with them.

There’s a long-running debate about how much of Nigeria’s history is actually taught in local schools.

“I remember there was only one paragraph about the Biafran War in our world history textbook and the book was over a thousand pages long,” Maryam Isa, a 25-year-old English teacher in the Nigerian capital of Abuja, said about her secondary school education. “I didn’t even know it happened until I read it.”

Last week, pro-Biafrans commemorated the 50-year declaration of the Republic of Biafra by staging stay-at-home demonstrations. For some, May 30 was a day to remember those who died fighting for Biafra. For others, it was an opportunity to keep demanding the actualization of the Republic of Biafra. Many commercial areas in southeastern Nigeria shut down last week. Even in Abuja, pro-Biafrans, did not show up for work, according to a local source.

The Nigerian social media world has lit up with commentary about the war. There’s finger pointing, rants and everything in between. Some accuse western media and the Nigerian government of downplaying the often-quoted Nigeria-Biafra war death toll. Some accuse pro-Biafrans of exaggerating what happened while others accuse the media of ignoring the fact that southeasterners were not the only ones killed.

The commentary reveals an uncomfortable reality: there’s a pervasive misunderstanding of the events that changed the course of Nigeria and unfolded just half a century ago.

With a median age of 18 years, Nigeria’s population is a young one. The overwhelming majority were born long after the war. Those old enough to have been through it often note young Nigerians are either demonizing or romanticizing Biafra, because they don’t really know what happened during the war.

Many say it is time for the Nigerian government to formally discuss “the Biafra issue” or as literary giant Chinua Achebe termed it, the “Igbo question.” Some pro-Biafrans want a violent breakaway from Nigeria. Others are demanding a #Biafrexit referendum to determine if the southeast should stay in Nigeria.

It’s a reminder that wounds have not healed. Just underneath the scabs, ethnic hostilities are still bleeding.

In conversations about the war, those hostilities gush forth, red and raw, painfully pitting one ethnic group against another in an “us-versus-them” mentality. One ethnic group accuses another of betrayal, or of ethnic cleansing. There’s also a play safe mainstream “We’re all Nigerians” attitude which prevents conversations about the war from happening, in a bid to avoid flaring up accusations of “tribalism.”

Many questions about the war itself remain unanswered. How widespread was the raping of Biafran women and girls by soldiers of both sides? How many Biafran children were airlifted to Gabon? How many civilians did Nigerian troops kill in one of its worst tragedies in Asaba?

In the vast void of answers, suspicious have been planted. There, they’ve grown and hardened hearts and minds. Among many Igbo people today, the suspicion that the Nigeria-Biafra War was an attempt by the Nigerian government to wipe out the Igbo race is firmly rooted. The word ‘genocide’ is tossed back and forth like a bloody rag that no one wants to catch.

For the sake of Nigeria to move forward as a nation, there’s a need to look at the bloodstains on the rag and have frank conversations about the war.

This is why Nigerian journalist Patrick Egwu’s recently published stories about war veterans is so important. In my own attempt to preserve history, I have begun archiving first-hand accounts at www.biafranwarmemories.com of the war from people who remember it.

Last month, an Abuja-based foundation conducted a civic dialogue forum about Biafra. The acting Nigerian president Yemi Osinbajo attended and appealed for national unity during his keynote address.

The event was the first of its kind—a Nigerian government-approved forum about the war. It actually took place despite warnings from security officials and others that it shouldn’t hold because it could incite ethnic tensions. But, how deep the dialogue at the forum went is up for debate. Some participants said the event only skimmed the surface and that speakers gave politically correct or even whitewashed speeches.

While the event was being planned, I had asked the organizer if there would be any mention of the infamous murder of civilians by Nigerian troops in the town of Asaba during the war.

“No,” was the answer. “The Asaba Massacre is too controversial.”