The end of “peak TV” must finally, mercifully be nigh

Did you watch the latest season of Black Mirror? How about Handmaid’s Tale? In the age of “peak TV,” this classic water-cooler conversation starter induces more anxiety than enthusiasm for television series. As long ago as 2015, when he coined the phrase “peak TV,” FX Networks boss John Langraf observed that there’s “simply too much TV.”

Did you watch the latest season of Black Mirror? How about Handmaid’s Tale? In the age of “peak TV,” this classic water-cooler conversation starter induces more anxiety than enthusiasm for television series. As long ago as 2015, when he coined the phrase “peak TV,” FX Networks boss John Langraf observed that there’s “simply too much TV.”

Indeed, nearly 500 scripted series aired on US TV last year; 487 to be exact, up from 455 in 2016, according to FX Networks’ annual study of scripted-TV programming.

Most were commissioned by online platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu. Social networks such as Facebook also got in the TV game with full-length series in 2017.

Those platforms have been spending furiously to ensure that they’re among the handful of video services audiences subscribe to each month. Netflix spent roughly $6 billion (paywall) on programming in 2017, Amazon spent $4.5 billion, and Hulu shelled out another $2.5 billion. Meanwhile, Disney, which recently agreed to buy rival 21st Century Fox, has two subscription-streaming services on the way, and tech companies like Apple are pushing further into original content.

Yet, audiences are suffering from fatigue. US audiences say they have more TV and streaming services now than they know what to do with; the average US viewer has access to about four, but only uses about two online services regularly, consultancy PWC found (pdf) in 2017. About half of US viewers said there are so many TV shows to choose from it’s hard to know where to start, Hub Entertainment Research found in a 2017 survey. And fewer people—73%, compared to 81% in 2014—say they’re devoting more of their total TV time to shows they really like.

“For a lot of consumers, there’s so much stuff they need to watch it’s sort of like homework,” said Toby Chapman, an associate partner at global strategy consultant OC&C.

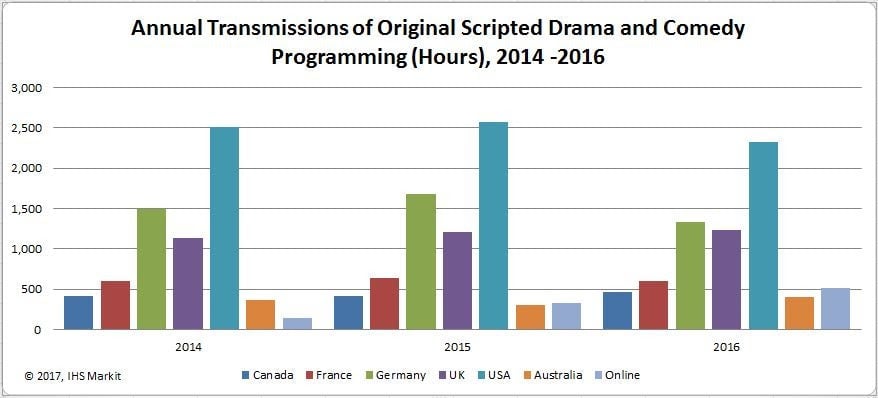

Landgraf predicted two years ago that TV would peak in 2018 and decline the following year. The industry then was “in the late stages of a bubble,” he told the 2015 Television Critics Association summer press tour. Now, broadcasts of scripted dramas and comedies, which have fueled most of the flood of scripted fare as of late, have fallen off in countries like the US and Germany, research firm IHS Markit found. US broadcast and cable networks aired 2,323 hours of original drama and comedy in 2016, down from 2,511 hours in 2014.

“The fall-off in production of originals we’ve observed in US cable and Germany shows that in some markets, the supply of drama is starting to outstrip demand,” said Tim Westcott, research director, channels and programming at IHS Markit, in an October study. “It also shows that TV schedulers have other genres of appealing programming that they can call on, such as scripted reality, entertainment formats, or comedy gameshows. These are often both cheaper and less risky than drama in particular.”

It seems, then, that the end of the TV-content bubble may finally, mercifully, be nigh.

Budget woes

Netflix, for one, can’t keep up its current spending. It plans to spend about $8 billion on programming this year, up from around $5 billion in 2016, as it works to balance its library with half originals and half licensed content. It’s burning through cash and taking on debt to pay for it. Netflix had $20 billion in content commitments, as of last year, including $4.8 billion in long-term debt and $15.7 billion it estimated it would owe from deals with content partners.

The streaming-video giant started commissioning its own TV shows in 2012 to differentiate its subscription video-on-demand platform from traditional-TV channels and competing services like Hulu and Amazon Prime Video. The exclusive content gave customers reasons to subscribe, and continue to do so month after month.

Now that it has a foothold in TV, more of that money is going toward movies. Netflix plans to release 80 films in 2018, up from around 60 this year. “They range anywhere from the $1 million Sundance hit, all the way up to something on a much larger scale,” said chief content officer Ted Sarandos on an October conference call. Netflix’s first blockbuster Bright cost $90 million last year and it green lit a sequel, as well as Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, for 2019, which has an even higher estimated budget.

The big four US broadcasters—ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox—and the CW ordered fewer new series for the 2017-2018 TV season than the season before. In fact, they green lit the fewest shows in five years, with just 39 new scripted shows ordered during the annual TV upfronts this past May.

They’re also giving new shows more time to catch on with viewers, rather than canceling them as soon as a few episodes miss ratings expectations. There were 19 freshman shows renewed among the same five TV networks during the 2017 upfronts, more than the 16 in 2016, the Hollywood Reporter reported. That’s partly because live TV ratings don’t mean as much as they used to. Lots of shows are discovered after they originally aired on-demand and on platforms like Hulu. Marketing, production, and distribution costs make launching a TV show expensive, so better to stick with something than kill it before it has a chance to gain traction.

Meanwhile, premium- and basic-cable channels like HBO and FX, respectively, are extending the lifespan of their biggest shows by spacing out the seasons. The finale of Game of Thrones won’t air until some time in 2019, two years after the penultimate season. Viewers also had to wait more than a year for the second seasons of Westworld and FX’s acclaimed dramedy Atlanta.

Aside from networks clinging to their most lucrative properties, talent to create shows isn’t infinite. Atlanta creator and star Donald Glover had time to put out another Childish Gambino album, shoot his scenes as Lando Calrissian in Solo: A Star Wars Story, sign on to star as Simba in the live-action reboot of The Lion King, and ink a deal to co-produce and write an animated Deadpool series for FX after the first season of his FX show. It makes signing on for a series a lot more attractive to sought-after showrunners and stars like him.

“There’s not an infinite supply of top-tier talent that can make high quality shows,” said Chapman at OC&C. “Even if the money was there to make hundreds of drama series with production budgets of $2-3 million an episode, some of them are not going to be quality because the pool of talent is constrained.”

Cheaper alternatives

Scripted-TV programming already peaked among basic-cable networks like FX and AMC, in 2015, FX found, though those basic-cable channels still comprise the bulk of scripted TV.

Some networks, like WGN, A&E, and the National Geographic Channel, have been forced to pull back on the high-end scripted dramas that have captivated audiences since the debut of The Sopranos in the late 1990s. The critically acclaimed drama Underground, for example, was a hit for its network WGN America by most measures. But it didn’t draw enough viewers to justify the spending. The network cancelled the prestige show after its second season, along with its other remaining scripted dramas, last year.

Earlier in 2017, A&E also cancelled its last scripted show, Bates Motel, completing its pivot away from scripted programming. It’s focusing instead on reality shows like Leah Remini: Scientology and the Aftermath and 60 Days In. Oxygen, a network geared toward women, rebranded this year to focus on crime stories, following the success of podcasts like Serial, and crime documentaries like HBO’s The Jinx and Netflix’s Making a Murderer.

“The scripted department is doing an amazingly good job of trumpeting their successes above and beyond what the numbers prove,” said Mark Koops, of INE Entertainment, which produces unscripted shows like The Biggest Loser and Masterchef. “The ratings backbone of these networks is unscripted programming that’s produced at a fraction of the cost.”

Networks like Fox News, ESPN, MSNBC, and HGTV that offer live and unscripted programming were among the most-watched cable channels of 2017. Meanwhile, US channels like Pivot, Chiller, and the Esquire Network, have folded, as skinny bundles give audiences the ability to pick and choose the channels they want—and don’t want—to pay for.

Tech is still spending

Still, precisely when the bubble will burst is difficult to predict.

Big technology companies with cash to spare like Apple, Facebook, YouTube, and Snapchat are getting into the game even while their video efforts may not constitute “TV” in the strictest sense. Snapchat doesn’t even play on TVs. But they are giving way to a larger video-content bubble that will span platforms like Snapchat and YouTube, and may change the very definition of “TV” among audiences who are as comfortable viewing on a smartphone as on a TV.

Meanwhile, a slow down in the hour-long dramas and 30-minute comedies we typically think of as TV today may be a welcome reprieve for viewers. They may actually have time to catch up on the shows they couldn’t squeeze into their regular viewing. Some of the best shows on TV, like The Americans and The Leftovers, have been overlooked by viewers because there’s too much competing for their attention.

As Titus Andromedon in the fictional Netflix sitcom Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, “you know you’re in a golden age of TV when you take a show like The Americans for granted.”