A crypto platform is the world’s largest buyer of carbon offsets

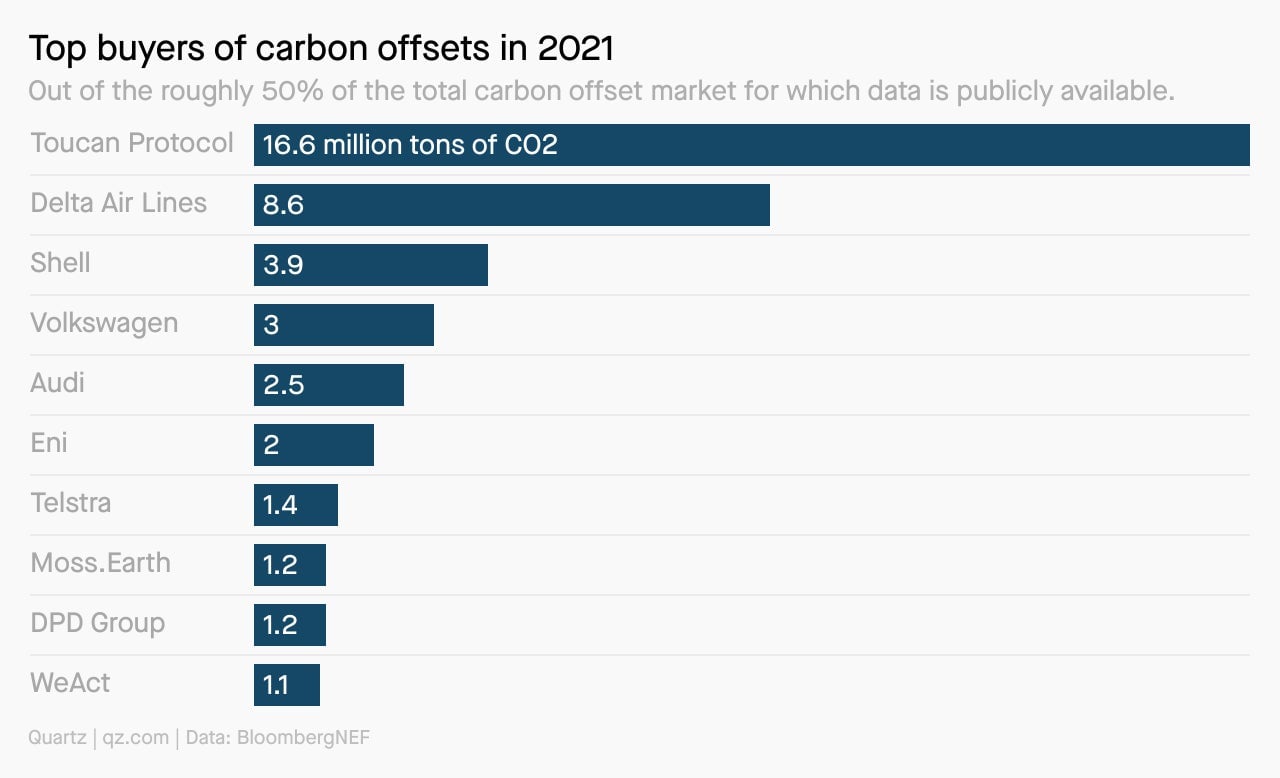

Cryptocurrency platforms, airlines, carmakers, and oil companies were the biggest buyers of carbon offset credits in 2021, according to a new Bloomberg analysis of data from Verra, the largest offset brokerage. At the top of the list by far was Toucan Protocol, a crypto trading platform that snapped up carbon offsets worth 17 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Cryptocurrency platforms, airlines, carmakers, and oil companies were the biggest buyers of carbon offset credits in 2021, according to a new Bloomberg analysis of data from Verra, the largest offset brokerage. At the top of the list by far was Toucan Protocol, a crypto trading platform that snapped up carbon offsets worth 17 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Carbon offsets ostensibly allow their purchaser to claim a reduction in their carbon footprint, since the money goes toward supporting a project—most often renewable energy systems or forest conservation—that keep new greenhouse gas emissions out of the atmosphere. In theory, carbon offsets should be a way for high-carbon companies that cannot affordably cut emissions directly to finance carbon cuts elsewhere, effectively drawing down net emissions. But in practice, many offsets are based on dubious assumptions and calculations that provide a veneer of climate progress without actually reducing emissions.

Toucan’s goal was not to offset its own corporate emissions but to turn the offsets into digital tokens that its customers could trade on its platform, creating another tradeable commodity with an ostensibly green core. In fact, Bloomberg found, most corporate offset purchases were made with customers in mind, in order to offer specific products—from seats on a flight to shipments of natural gas—that could be upsold as “carbon neutral.” (Data on offset trading is limited to what buyers and sellers voluntarily disclose, so the Bloomberg analysis covers only about half of the total global market).

Crypto’s time at the top of this list is probably over, at least for now. In May, Verra said it would ban the “tokenization” of offsets, because doing so created what one Verra executive called a “mind frying” level of abstraction and distance between an intangible financial instrument and the physical emissions it is meant to represent. Still, both Toucan and Verra are continuing to tinker with ways to more credibly link carbon offsets to cryptocurrency technology.

The biggest problems with carbon offsets

Even booting crypto companies from the offset market wouldn’t fix other entrenched problems. The biggest is the concept of “additionality”: If not for the sale of an offset credit, might a block of forest have been cut down, for example, or a solar farm never built? If the forest was never at risk, or the solar farm financial viable regardless, then the offset purchaser is effectively subsidizing an activity that would have happened anyway, and therefore exerting no real downward pressure on global net emissions. (An offset derived from a carbon removal facility, on the other hand, has a stronger, more easily quantifiable chain of cause-and-effect. It is, therefore, “additional.”) Additionality is notoriously hard to prove, but it is especially problematic for clean energy and “avoided deforestation” projects—which together were the source of 90% of offsets purchased in 2021.

Another problem is that most offsets are old: 60% of offsets purchased in 2021 were originally created in 2015 or earlier, Bloomberg found, when rules for how offsets are calculated were even more lax. That means a purchaser is erasing from its current balance sheet a ton of emissions that was avoided years ago and may never have been additional to begin with. Only 0.2% of offsets sold in 2021 were created in that year.

The final problem is geographical. The vast majority of offsets are derived from projects in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, and sold to buyers in Europe and the US. These transactions create an accounting problem. If Company X in the US buys 100 tons of emissions from a forestry project in Vietnam and deducts those from its carbon footprint, eventually that figure is folded in to economy-wide estimates of US emissions, which appear to shrink. But there’s nothing stopping the project developers in Vietnam from counting those same 100 tons against that country’s carbon footprint. So on paper, global emissions appear to have dropped 200 tons.

Climate negotiators at last year’s COP26 in Glasgow agreed in principle on rules to deal with most of these issues, and last week published a first draft of “core carbon principles” that an offset must meet to garner an international seal of quality. Those rules are open for public comment until Sept. 27.

But even after they’re adopted, they will be guidelines, not legally binding, which means the carbon offset market is likely to remain awash in junk for the foreseeable future. And as more companies face pressure from their customers and governments to demonstrate progress on climate, the offset market is rapidly growing. Bloomberg predicts its total value could reach $190 billion by 2030—up from just $1 billion today.