A hidden system of exploitation underpins US hospitals’ employment of foreign nurses

Faced with an unprecedented staffing crisis, some hospitals are turning to a captive workforce

This series was produced in partnership with the nonprofit newsroom Type Investigations, with support from the Gertrude Blumenthal Kasbekar Fund, the Puffin Foundation, and the Pulitzer Center.

TALLAHASSEE, Florida — When Rachel started her job as a nurse in the internal medicine unit at Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare last year, it felt like the realization of a dream that was years in the making.

A slight, soft-spoken Filipino woman, Rachel, 31, had spent her career working in hospitals across the Philippines, struggling to care for patients in the country’s under-resourced healthcare system. In the US, by contrast, she would have access to essential medicines, MRI machines—all the latest treatments and technologies modern medicine has to offer. She would also receive a coveted US green card, and be paid far more than she could make at home.

“I was excited,” Rachel said of the weeks before she boarded her flight to Tallahassee in August 2022. “It’s the US. It’s the most glamorous place.”

At Tallahassee Memorial, that was true enough. The hospital, gleaming and modern, is rated among the top healthcare facilities in the region. The only resource missing? Time. Rachel, who was an emergency room nurse in the Philippines, was assigned to the internal medicine unit at Tallahassee Memorial, where she had to quickly learn the new specialization. She and her colleagues would regularly juggle as many as five patients at one time, straining them to their limits. Sometimes they had to care for as many as seven patients each.

Sliding a needle into an elderly patient’s papery vein could take up to half an hour, Rachel said. Another patient might become combative, lunging to hit her, and it would take even more time to calm him down. Meanwhile, other tasks would pile up: wounds to clean, feeding tubes to replace, diapers to change, not to mention all the paperwork for admissions, transfers, and discharges. With three patients, Rachel was confident she could provide the care they needed. With five or more she was scrambling to keep up.

Soon, Rachel found herself spinning through the cycle of anxiety, burnout, and guilt about a job hastily done that has plagued nurses across the US and accelerated during the covid-19 pandemic. According to research by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 45 percent of nurses surveyed in 2022 reported experiencing burnout, and nearly one-fifth of the current workforce plans to leave the profession by 2027. An American nurse who started at Tallahassee Memorial at the same time as Rachel quit two months into the job. “The work is just terrible,” a colleague of Rachel’s remembered him saying.

But Rachel couldn’t quit so easily. Her employment contract with Tallahassee Memorial committed her to working for the hospital for at least three years and barred her from changing departments for at least one year.

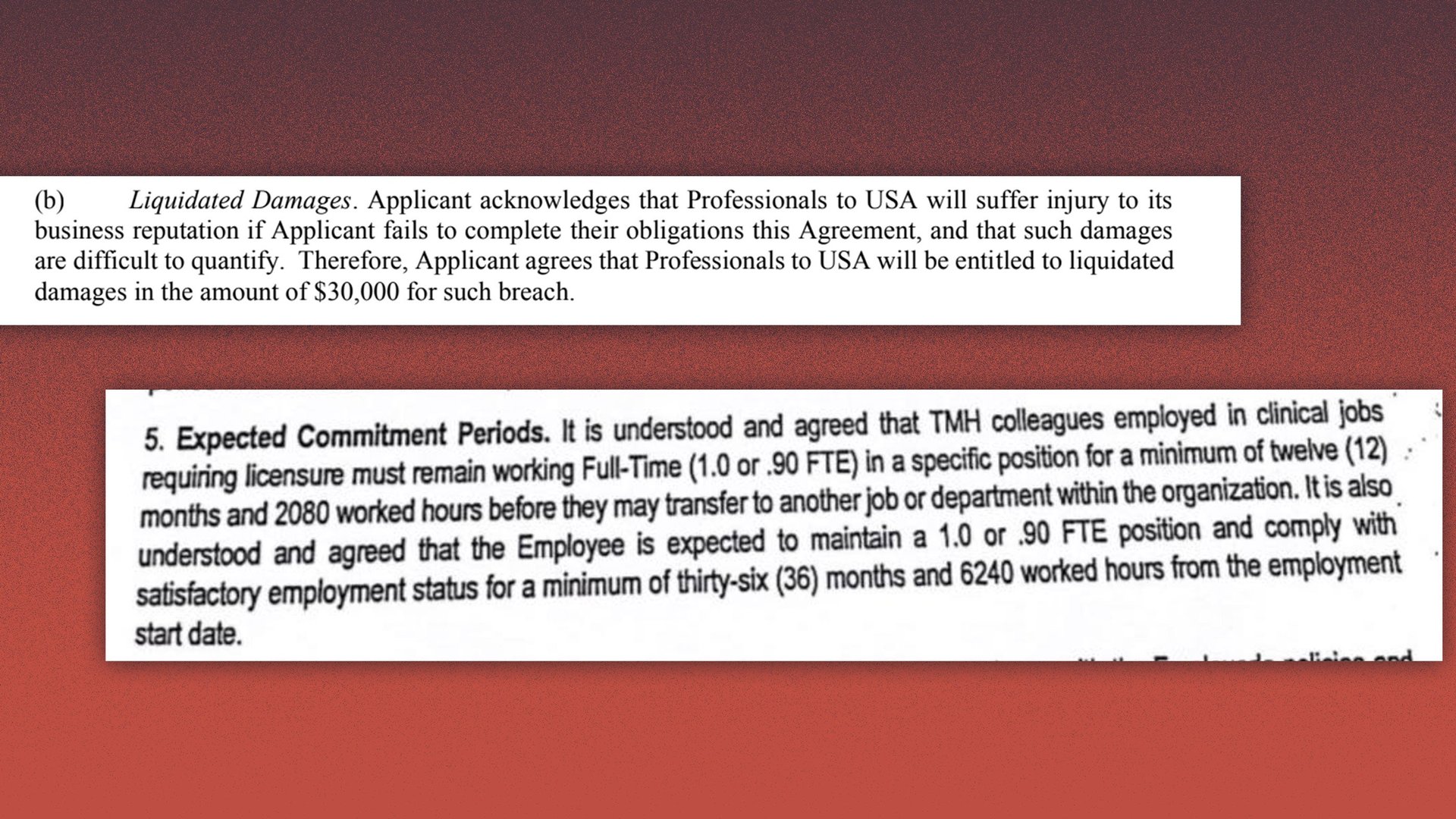

Moreover, Rachel had also signed a contract with a Florida-based recruitment agency, Professionals to USA (PTU), that had arranged the job at the hospital and handled her immigration paperwork. The agency had charged her a $2,500 fee as part of the application process, she said, and she had to shoulder thousands of dollars in additional costs, such as a job offer letter and a medical clearance exam. Rachel also said her PTU contract included a $30,000 breach fee, a common practice among agencies that recruit nurses to work in the United States.

Quartz and Type Investigations reviewed a PTU contract signed by another Filipino nurse who started working for Tallahassee Memorial around the same time as Rachel. It specified that if the nurse violated the terms of the contract, she would need to pay the agency $30,000 in damages, ostensibly to cover the reputational harm PTU said it would suffer if the nurse left her job early or otherwise breached the contract. The agency’s CEO also suggested in social media posts that he would report nurses who didn’t fulfill their contracts to immigration authorities.

Rachel, who asked to be referred to by a pseudonym because she feared retaliation from Tallahassee Memorial and Professionals to USA, is one of thousands of nurses who immigrate to the United States each year, the majority of whom come from the Philippines. During the early days of the covid-19 pandemic, from February to April 2020, the US healthcare sector shed more than 1.5 million jobs, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics — nearly 10% of the total healthcare workforce — contributing to a critical shortage in the nursing profession. For the United States, along with the United Kingdom and other European countries, hiring nurses from overseas has become an essential way to fill the gap.

For many foreign nurses, working in the US can provide opportunities for education, career advancement, and higher pay. But a year-long investigation by Quartz and Type Investigations, with funding from the Pulitzer Center, found that some nurses from the Philippines have been subjected to exploitative labor contracts that can trap them in their jobs and intimidate them into silence.

Quartz and its partners spoke with migrant nurses in Florida and other states, including nine nurses who were recruited to work at Tallahassee Memorial through Professionals to USA. To keep them in line, many of these nurses said, PTU or its CEO threatened to sue nurses for tens of thousands of dollars in contract breach fees or report them to immigration authorities if they left their jobs early. This type of treatment is pervasive in the international nurse recruitment industry, according to lawsuits against other agencies and interviews with nurses and advocates.

In some cases, high contract breach fees and threatening disobedient workers with deportation may violate laws against human trafficking and forced labor. But the work of recruitment and staffing agencies often falls into a regulatory gray area. Although some state and federal agencies are beginning to try to address these issues, enforcement is inconsistent, contributing to exploitative practices in the international nurse recruitment industry. Entities like the US State Department, the Department of Labor, the Justice Department, and state attorneys general could do more to help workers, experts say.

Such practices can impact not just nurses, but patients as well. Rachel said she feared that understaffing in her unit at Tallahassee Memorial put her at risk of making a serious error. She felt anxious before her shifts, and anxious after them. She barely ate and had trouble sleeping. She spent her days off struggling to cope, lying in bed, toggling between numbing TikTok videos of cute puppies and job openings her contract prevented her from pursuing.

In a statement to Quartz and Type Investigations, PTU’s founder and CEO Raymund Raval denied threatening to report nurses to immigration authorities and defended the agency’s inclusion of breach fees in its contracts. “Some of our contracts do include a ‘liquidated damages’ amount. That is not a ‘breach fee’ and is not illegal in the case of permanent visa immigrants,” Raval said. “The liquidated damages provision is not intended as a penalty, but is a normal way of agreeing to damages in the case of breach when damages cannot be reasonably calculated.”

A spokesperson for Tallahassee Memorial said in a statement that its priority is “creating an environment of engagement and support for everyone who comes through our doors,” and that all employees are treated with dignity and respect. “For many years, TMH has recruited nurses and other medical professionals from the Philippines,” the spokesperson said. “These colleagues are valued members of our TMH family, and many have been with us for years and are leaders in our organization.”

Faced with the $30,000 breach fee and the threat of being deported, however, Rachel said felt she had no choice but to remain in the job, even as it eroded her mental health. The experience made her question the decisions that had led her to Florida and drained her desire to continue in the profession she’d once loved.

“I came here for a better life,” Rachel said. “But it’s only become harder.”

The agency

When Raymund Raval appeared at a recruitment event at the luxury Shangri-La hotel in Manila in January 2020, one nurse said she felt “starstruck.”

Raval came across as dapper and charismatic, dressed smartly in designer clothes. He was Filipino and spoke flawless English, peppered warmly with Tagalog, the primary language of the Philippines. His pitch was enticing: You can work in your unit of specialization, he told the assembled nurses. They would be hired directly by Tallahassee Memorial, and PTU wouldn’t skim money from their paychecks like other recruitment agencies have been known to do, he said.

“We don’t get anything from this,” the nurse, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation from PTU, remembered Raval saying. “Not one peso.”

They would be paid $30 an hour, maybe more, PTU told the nurses, compared to the few hundred dollars a month most nurses could expect to make in the Philippines. All they had to do was pay a few thousand dollars to PTU to process their paperwork. A representative from Tallahassee Memorial was also at the event, ready to meet any nurses who were interested in relocating.

For the nurses in attendance, it felt like the first taste of the luxury that awaited them in the United States. “If you want to go to the US,” another nurse thought to himself as he walked into the sparkling Shangri-La, “this is it.” He asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation from the agency.

Raval has been in the international nurse recruitment business for more than two decades. Based in Gainesville, Florida, his company was founded in 2000 as Nurses to USA before changing its name to Professionals to USA in 2010. As a prominent recruiter, Raval is celebrated in the Philippines. In 2019, a Philippine TV news network referred to him as a “Global Pinoy Idol,” using the Tagalog slang word for Filipino.

In its first 23 years of business, Raval has said, the agency has arranged for more than 2,200 nurses from the Philippines to work in American healthcare facilities. In addition to providing international staff to Tallahassee Memorial, PTU’s website says it also recruits nurses for University of Florida hospitals in Gainesville, Leesburg, and the Villages, the sprawling retirement community outside Orlando.

Since the start of the pandemic, PTU says it has also expanded its business beyond Florida, bringing on new clients including Stormont Vail Health in Topeka, Kansas, and Archbold Medical Center in Thomasville, Georgia. On his Facebook page, Raval said that PTU was accepting applications not just from Filipino nurses, but also from nurses from Ghana, South Korea, and Japan. The company placed 252 nurses in US hospitals between December 2021 and July 2022, Raval announced on his Facebook page. By December 2022, he was congratulating himself on Facebook: “We SOLVED the Nursing Shortage in Tallahassee !”

Raval’s Facebook page is a non-stop scroll of motivational tips and smiling nurses just arrived on American soil. But amid the uplifting messages about the good life that awaits nurses in America, posts on PTU’s and Raval’s personal Facebook pages also leveled what seemed to nurses like thinly veiled threats.

“Kindly HONOR your 3-year commitment to the HOSPITAL which filed for your US IMMIGRANT VISA,” he scolded nurses in an August 2022 Facebook post, after at least one Tallahassee Memorial nurse’s employment was terminated. “We are in the business of Recruiting and Bringing you to America to have a better life. We are NOT in the business of filing a lawsuit.”

In a video he posted on Facebook that month, Raval filmed himself walking through the Atlanta airport, an American flag hanging from the rafters above him. He had just spoken with an immigration officer, he said with a frown, who told him that he could report nurses who didn’t finish their contracts to US authorities. “So he gave me the information, who to report them and give them their Social Security numbers and names. They can’t just come into the country and utilize the immigrant visa and leave, without fulfilling their commitment,” Raval said. “I’m sorry, but I have to report. I do have to report you all.”

In the caption, Raval suggested that nurses who did not finish their contracts could have trouble entering the US again. “The next time you go to AMERICA, your names and passport copies would probably be forwarded to the port of entry,” he wrote in a mixture of English and Tagalog. “It’s not a scare tactic, it’s what the Border Patrol from Atlanta told us earlier.”

In a statement, Raval said his warnings were simply intended to dissuade nurses from using his company to obtain green cards if they didn’t intend to remain in their jobs. “We have never threatened to report nurses to USCIS,” he told Quartz and Type Investigations. “We have had communications with USCIS when the facts indicate that the nurse applied for immigration with fraudulent intent, and we do warn all applicants to not file with us if their intent is fraudulent. It is rare, but once in a while a nurse simply does not show up for work at the hospital who sponsored them.”

Foreign nurses typically enter the United States on EB-3 visas, which grant them permanent residency. These workers can change jobs without risking their green cards as long as they came to the US with the intention of working indefinitely for the employer that sponsored their visas. A spokesperson for the US Citizenship and Immigration Services said employment agreements “are outside the scope of USCIS.” The Department of Labor said in an email that the agency “doesn’t have a role in enforcing the contracts of EB-3 visa holders.” US Customs and Border Protection, whose officers review passports and immigration documents at airports and other points of entry into the country, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Even so, Raval’s video played on nurses’ fears about what could happen to them if they quit their jobs. Raval had helped give them the opportunity to come to America. And if they didn’t behave, they believed, he could take it away.

Payments and hidden paperwork

For Rachel and other nurses, the cost of securing a job through Professionals to USA was high.

In addition to what Rachel paid to PTU, she also shelled out for plane tickets in the Philippines to take her licensure exams, then others to the US once she obtained her visa. She also paid for the related costs of travel, like hotels. All told, she said, she spent nearly $8,000 to come to America for the job at Tallahassee Memorial.

Requiring workers to pay money to take a job overseas violates internationally agreed-upon fair recruitment practices, according to the International Labour Organization, the UN agency that sets labor standards and works to prevent human trafficking and forced labor. According to the ILO, prospective employers should bear the costs of hiring, and workers should not be charged fees related to their recruitment, directly or indirectly. Such fees, as defined by the ILO, include recruitment and placement fees, the costs of verifying skills and qualifications like nursing board certifications and English language proficiency, travel and lodging costs, and costs associated with applications and legal representation.

The US government is aware that the process of bringing in workers from overseas can lead to exploitation.

“Practices that lead to human trafficking often occur in the recruitment process before employment begins, whether through misrepresentation of contract terms, the imposition of recruitment fees, the confiscation of identity documents, or a combination of these,” a State Department spokesperson told Quartz and its partners in an email. “The involvement of intermediaries (for example, labor brokers, middlemen, employment agencies, or recruiters) creates additional layers in the supply chain and positions these individuals to either assist or exploit.”

CGFNS International, a Philadelphia-based organization that screens international nursing credentials for visa applications, has cited recruitment fees as a primary red flag that international nurses should watch out for. “No recruiter should charge you a recruitment fee for their services,” the organization wrote in a 2022 blog post.

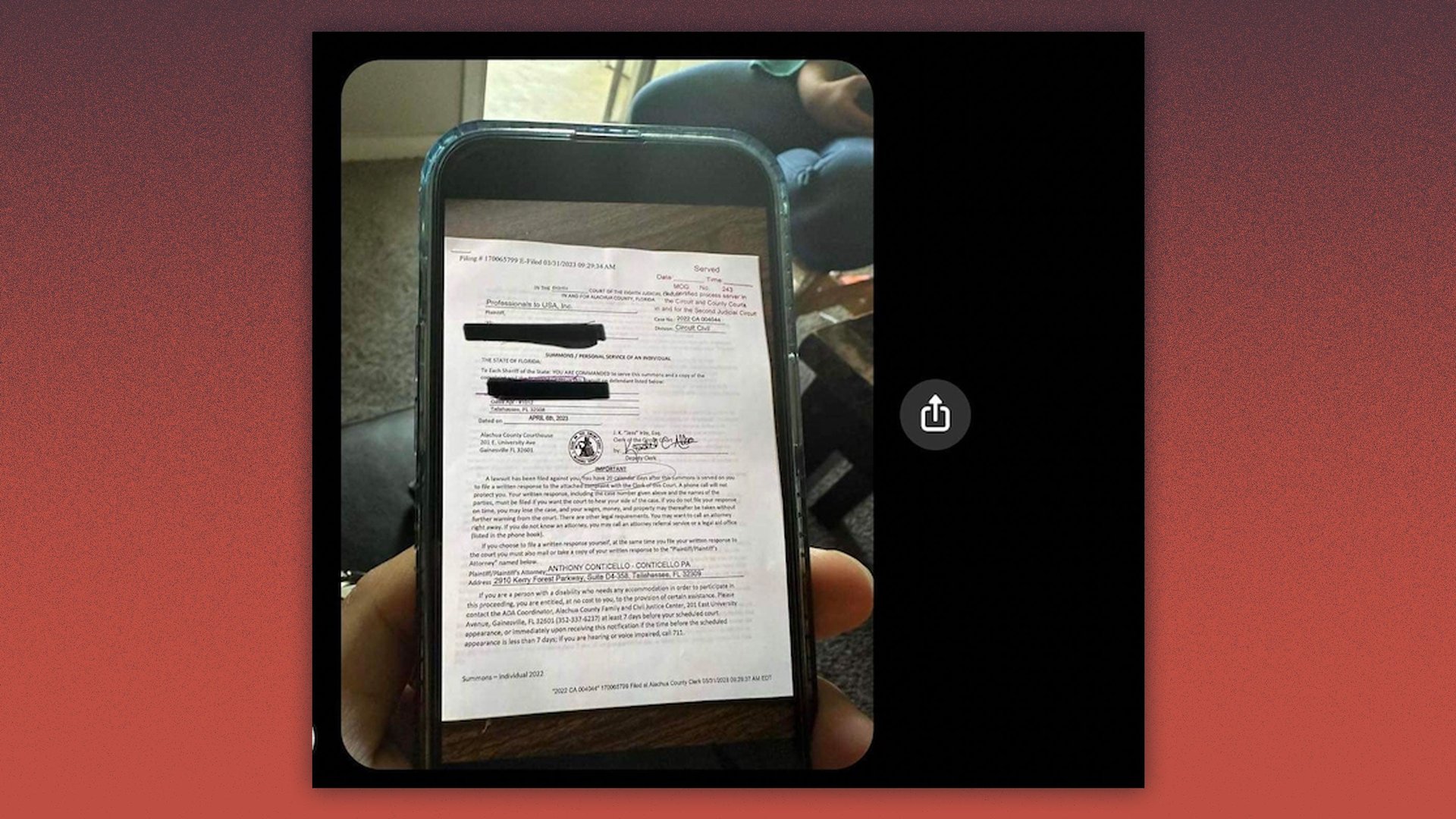

In December 2022, PTU filed a lawsuit against a nurse alleging that he had violated his PTU contract by leaving his job at Tallahassee Memorial before the end of his three-year commitment period, and seeking $40,000 in damages. In a legal filing, the nurse denied PTU’s claims and alleged that the agency’s high breach fee and threats of deportation and lawsuits violated federal anti-trafficking laws. The case is ongoing.

In a statement to Quartz and Type Investigations, Raval said PTU does not currently charge nurses a recruitment fee. “Our contracts have evolved over time in response to changing laws, norms and economic realities,” Raval said. “In our current contract with nurses, the nurses do not pay us anything. In most cases, we do require our nurses to pay the USCIS a ‘premium processing’ fee. The hospitals that we recruit for reimburse this fee to the nurses or pay them a relocation bonus or allowance that exceeds that amount.”

A PTU contract for a nurse placed at Tallahassee Memorial, which was reviewed by Quartz and Type Investigations, stipulates that the hospital will reimburse nurses for both the USCIS premium processing fee and relocation expenses. But nurses said Tallahassee Memorial covered only relocation expenses.

Tallahassee Memorial said it is currently reassessing its recruitment practices. “We are aware of the litigation involving Professionals to USA, Inc,” the Tallahassee Memorial spokesperson said. “While TMH is not a party to this litigation, we take matters like this very seriously. We are using this as an opportunity to review our recruitment relationships to ensure all colleagues feel respected and valued at TMH.”

The hospital did not respond to questions about the extent to which it reimbursed nurses for expenses.

In the paperwork US employers file to hire a foreign worker for a permanent position, the employer must specify whether they received any payment as part of the application process. Such payments can be a sign to US officials of an exploitative relationship, and can violate federal regulations that prohibit the buying and selling of permanent labor certifications.

Foreign employers who want to hire workers from the Philippines must also apply for accreditation with the government. The Department of Migrant Workers will not accredit an employer if its employment contract includes a liquidated damages provision, like the $30,000 breach fee in the PTU contract. The department did not answer questions about whether it had accredited PTU or reviewed its contracts. Raval said PTU partners with local licensed recruitment agencies, although Philippine officials say employers must be accredited directly.

And the relationships between workers and recruitment agencies can be easy to conceal. The counter claim against PTU filed earlier this year alleged that the US State Department began refusing nurses’ visa applications due to PTU’s recruitment fees and the high breach fee in its contracts. After that, several Filipino nurses said PTU discouraged them from disclosing their contracts with the recruitment agency to US officials or mentioning recruitment fees during consular interviews. If they mentioned the contracts, Raval implied, their visas might be denied.

When Rachel visited the US Consulate in Manila in 2022, she brought her official job offer from Tallahassee Memorial, which US officials reviewed before issuing her a visa. But Rachel did not show US officials her contract with Professionals to USA, following instructions she said Raval had given nurses in Zoom meetings.

When asked about cases in which contracts are concealed from the authorities, Saul De Vries, the Philippine embassy’s labor attaché in Washington, D.C., said that such agencies “are really hiding something.”

Raval, however, denied telling nurses to conceal their PTU contracts from US officials. “PTU has instructed nurses to provide all documents that the embassy asks for, including their contract with PTU,” he said.

PTU’s contract wasn’t the only agreement that placed restrictions on nurses. Once Rachel and another nurse arrived in the United States, they said Tallahassee Memorial added onerous terms to their hospital contracts. Rachel’s original agreement with Tallahassee Memorial, which Quartz and Type Investigations reviewed, did not specify how many years she would need to work for the hospital. But after she arrived in Florida, the hospital made her sign a new contract, which specifies the time commitment of at least three years.

Rachel and the other Filipino nurse said the hospital’s human resources department had them sign the new contracts during a group orientation, telling them they couldn’t start work until they did so. The nurses felt they had no choice but to sign, Rachel said.

A spokesperson for Tallahassee Memorial did not address the allegations in their statement.

A “high wave” of contract breaches

Recruitment and staffing agencies have filed major lawsuits against nurses in recent years, seeking tens of thousands of dollars in breach fees and damages — and sending a message to the rest of the workforce. “They try to collect [from] one nurse, and the nurses talk,” said Carmen Comsti, lead regulatory policy specialist at the California affiliate of National Nurses United, the largest union representing registered nurses in the US. “That’s all it takes to suppress the nurses’ voices.”

In 2019, the staffing agency Health Carousel collected a $20,000 fee from a nurse in Pennsylvania for leaving their job before the end of their contract. Sentosa Services, a Brooklyn-based staffing agency, sued three nurses in 2016 for $25,000 each for breaching their contracts, plus hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages. And in 2022, Advanced Care Staffing, another Brooklyn agency, initiated arbitration proceedings against a nurse who quit his job. The company told the nurse that it would seek damages of “at least $20,000,” plus attorneys’ fees and additional costs associated with the arbitration process, which the nurse’s lawyers said could add up to tens of thousands of dollars. CommuniCare, another international recruitment agency, sued nurses in 2022 for $100,000 for breaching their contracts.

High breach fees may run afoul of federal anti-human trafficking laws, according to experts, because they can act as threats of serious harm that coerce workers into remaining in their jobs. Some cases may also violate minimum wage or consumer protection laws. Lengthy commitment periods, like the three or more years specified in the contracts reviewed by Quartz and Type Investigations, undermine the free movement of labor and deny workers one of their strongest bargaining chips: the ability to quit their jobs if the conditions of employment don’t suit them.

In March 2023, the Department of Labor filed a lawsuit against Advanced Care Staffing to stop the agency from forcing nurses to work for three years or pay the company for projected future profits, attorneys’ fees, and the cost of arbitration, alleging that the practice is a violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act because it brings workers’ wages below federal minimums. “Employers cannot use workers as insurance policies to unconditionally guarantee future profit streams,” Solicitor of Labor Seema Nanda said in the department’s announcement.

David Seligman, a labor lawyer and executive director of Towards Justice, a nonprofit that has filed lawsuits on behalf of international nurses, including against Advanced Care Staffing, said the complaint is a major step toward greater government enforcement in this area, which could leave companies “on the hook for pretty massive exposure.”

A lawyer for Advanced Care Staffing said in March that the company was “deeply troubled” by the Department of Labor’s allegations, which it said were “unsupported by either the facts or the law.” The case is ongoing.

For now, however, no single US agency is responsible for regulating the nurse recruitment industry, and enforcement is scattershot. “There is no systematic mechanism for detecting forced labor in the healthcare field,” National Nurses United wrote in a July 2022 statement to the Department of Health and Human Services. Examples of coercive labor practices the union discussed only surfaced “in an ad hoc manner — through litigation, short-term research projects, or discussions among nurses.”

Nurses have filed a number of class-action lawsuits in recent years — and have won some significant victories. In 2019, a federal judge in New York ruled that Sentosa Services’s threats to enforce its $25,000 contract termination penalty violated federal human trafficking laws. More than 100 Filipino nurses were awarded a total of $2.5 million. In 2021, the New York attorney general found that a local hospital, Albany Medical, had illegally charged Filipino nurses for quitting or being fired, and ordered the facility to pay $90,000 to seven nurses.

But restrictive contract provisions don’t have to stand up to legal scrutiny in order to keep nurses in line. “Very often, employers and other corporations will put unenforceable terms in the fine print of contracts,” Seligman said. “Because enforcement is hard. And because very often, people are scared by that term. Even if no court would ever enforce it, people find it scary.”

Mukul Bakhshi, chief global affairs officer at CGFNS International, said the nursing industry is currently experiencing a “high wave of breaches.” As the pandemic-induced staffing crisis has increased demand for nurses, small agencies have popped up across the country, contributing to a Wild West of international nurse recruitment with agencies using increasingly aggressive tactics to keep workers from leaving their jobs. In some contracts, overtime and training hours don’t count toward a nurse’s total time commitment, adding months of work. Research published in 2007 found that nurses reported contract breach fees ranging from $8,000 to $50,000. But over time, these fees have crept up. Some agencies try to charge nurses as much as $100,000 for leaving their jobs, according to court records and interviews with nurses and advocacy groups.

“Since 2020, everything’s kind of exploded,” Bakhshi said about the practices employed by some agencies in response to the nursing shortage.

“They’ll just exhaust you until you’re demoralized”

In the absence of more thorough government oversight, nurses have banded together to protect themselves and push back against abusive working conditions.

At a complex of gray, low-rise buildings a few minutes drive from Tallahassee Memorial, Rachel and a few of her colleagues gathered at one of their apartments for a lunch of Filipino oxtail stew, served alongside a tidy stack of crisp spring rolls. The nurses, most of whom lived in the complex, supported each other as they navigated their new lives. They enjoyed nights out together at local bars and restaurants, went on road trips to the beach, and tried to make sense of the quirks of American culture and the ways it could be so different from what they were used to back home. That afternoon in October, however, the focus of their conversation was Ray Raval.

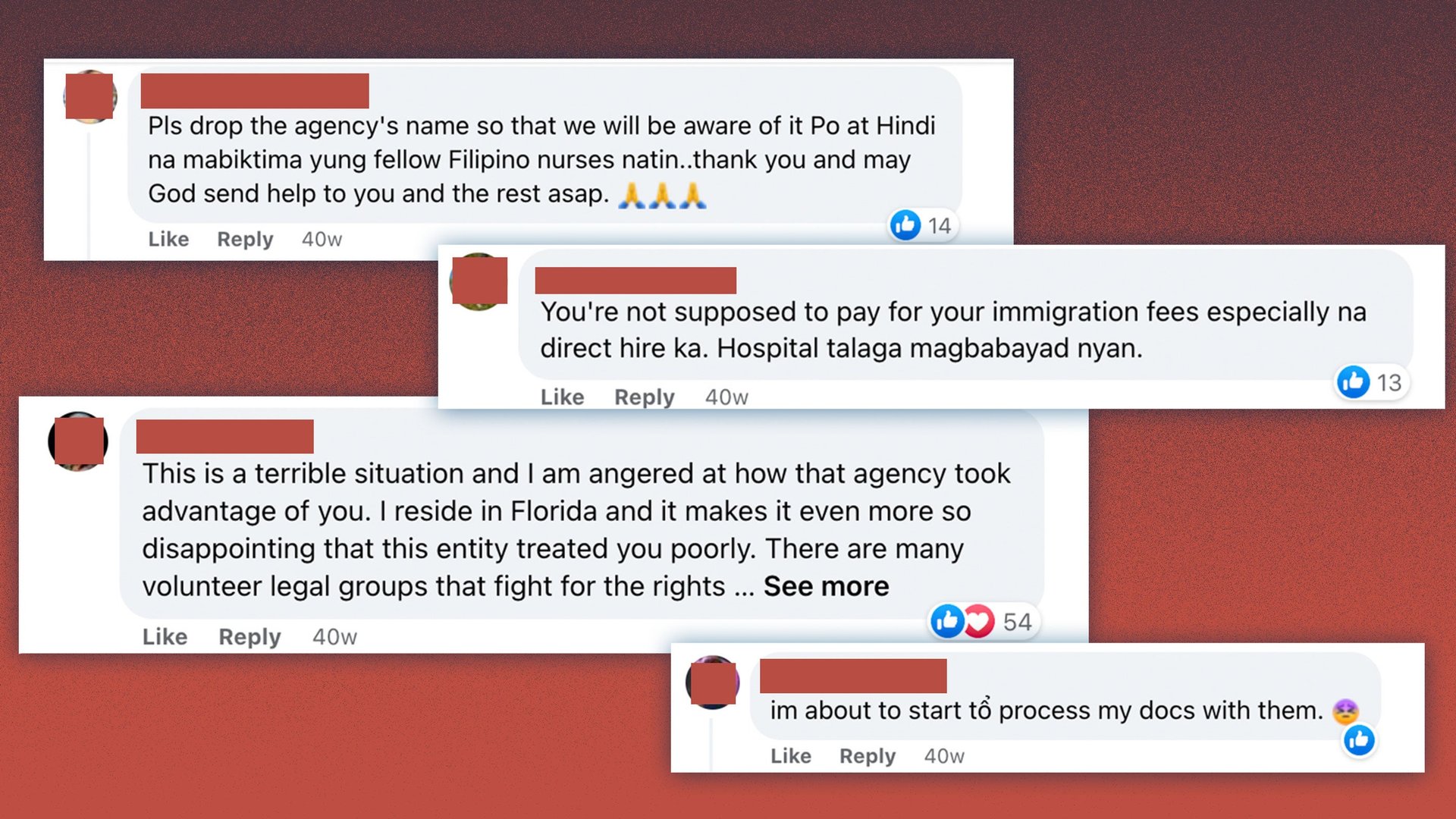

Ten days before, an anonymous post appeared on Lefora Filipino Nurses to US, a private Facebook group that currently has more than 200,000 members, where nurses share tips, celebrate success stories, and occasionally warn colleagues of exploitative situations. The post said an unnamed recruitment agency had been mistreating nurses by charging them thousands of dollars for job placement, locking them into their positions with $30,000 breach fees, breaking promises about the pay they would receive, assigning them to jobs outside their areas of specialization — or, worse, not placing them in jobs for months after arriving in the US, leaving them without earnings while stress and bills piled up.

“This is so frustrating,” the post read. “Hopefully no one else will be victimized by this agency.”

When US employers hire foreign workers for permanent jobs, they are required to attest to the government that they can place the employees on payroll by the time the workers enter the country. Tallahassee Memorial did not respond to a request for comment about the allegations that some nurses waited for months before the hospital gave them assignments.

The Lefora post generated a huge response among the group, and members demanded to know the agency’s name. While the original post avoided identifying the agency, several members of the group named Raval or Professionals to USA in the comments.

Three days later, on October 22, Raval issued a statement on Facebook addressed to the Lefora group. “Anyone on this board or elsewhere who says that we ‘double dip’ or are dishonest is lying,” he said.

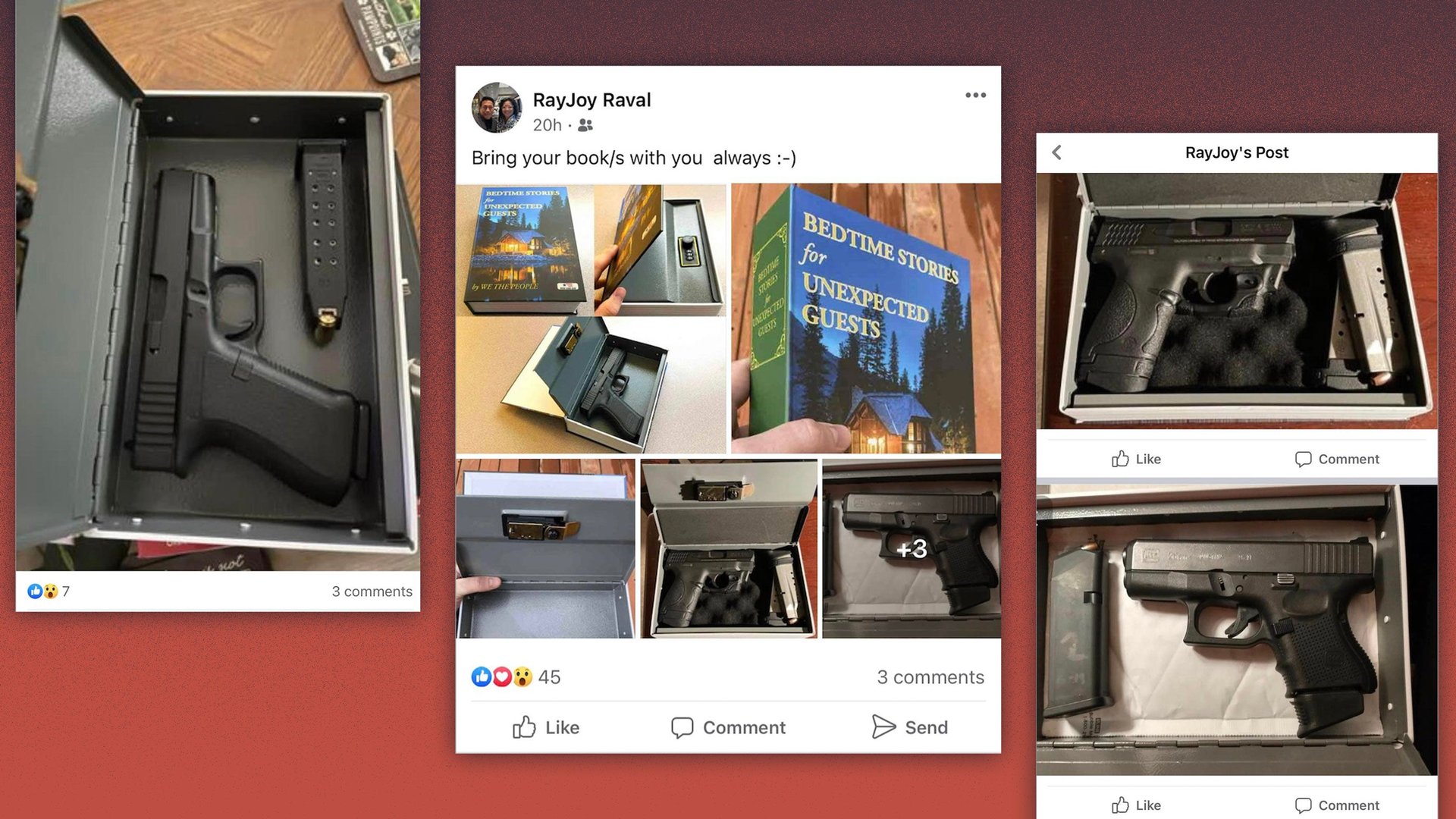

Raval also spoke about the Lefora post during a public Zoom meeting. “And then you cannot even talk in front of fucking Lefora? This is bullshit,” he said in a mix of Tagalog and English to the nurses in attendance, according to a recording of the meeting obtained by Quartz and Type Investigations. “Who is this person? I carry three guns, because these Filipinos will stab me. They better make sure that if they stab me in the back I’m no longer breathing, because I might just shoot them in the head.”

A week and a half after the post in the Lefora group, Raval posted photos on his Facebook page showing three handguns, concealed in metal cases designed to look like books. “Bring your book/s with you always :-),” he wrote in the caption.

If such posts seemed designed to discourage nurses from speaking critically of him, Victoria, a Filipina nurse in her 20s, had decided not to remain silent. “It means he’s getting really scared,” she said after scrolling through Raval’s Facebook feed, while sitting in her apartment in Tallahassee. Victoria had come to Tallahassee Memorial by way of PTU, and Raval’s treatment of her and other nurses had begun to rankle. As the author of the anonymous post on Lefora Filipino Nurses to US, she asked to be referred to by a pseudonym, for fear of retaliation by Raval and Professionals to USA.

Nervous as she was, the idea that Raval might be intimidated by her also struck Victoria as funny. If only he knew who he was scared of, she said, her fuzzy slippers kicked off at the foot of the sofa. “And if he saw me, I’m just here laying around,” she said. “And a woman at that.”

In a statement, Raval said he was not aware of the Lefora Facebook post that criticized PTU and denied threatening his critics. He brought up his guns, he said, during a discussion about anti-Asian hate crimes in the US. “In response to some questions about what I do for my personal security, I did say that I have a Florida concealed weapons license and carried a gun,” Raval said. “That is 100% normal in Florida and we do encourage all nurses who are interested to obtain training and licensure in their home state.”

“As a Filipino-American who immigrated to this country, I take the anti-Asian hate crime attacks very seriously and do not want to ever have one of our nurses unable to defend themselves,” he said. “As to what you have been told, I have never threatened anyone and certainly not with guns.”

Victoria had hoped that her post would prevent other nurses from being exploited. Through an administrator of the Lefora Facebook group, she brought Raval’s threats and the nurses’ complaints to the attention of the Philippine Nurses’ Association of America (PNAA), the main professional organization representing Filipino nurses in the US.

After the submission of the complaint, however, she was listening to one of Raval’s Zoom meetings, a rant that careneed from the war in Ukraine to an anti-abortion screed to criticism of whoring actors on TV, when he received a message from a man who identified himself as a representative of PNAA in Florida. The message said that someone had filed a complaint about a hospital in Tallahassee. The call alarmed Victoria, who worried that she might have been exposed.

But Victoria kept going. She said she filed a complaint against PTU with the Internal Revenue Service, but never received a response. She considered contacting the FBI, but it was difficult for her to work out how to navigate the system for filing complaints. She even sent an email anonymously to the Philippine embassy’s overseas labor office, which she said also did not respond. There was no clear way for international nurses to seek accountability, she felt. And whatever the laws and ethics might be, nothing would happen if no one enforced them. She spoke to a lawyer, which gave her some hope, but it was clear that any potential legal case would take a long time to resolve.

“They’ll just exhaust you until you’re demoralized,” Victoria said of the lack of response she received from PNAA and the authorities. “They have no teeth. That’s why agencies aren’t afraid to do sketchy contracts.”

The Philippine Nurses’ Association of America did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In April 2023, Victoria and her colleagues received a reminder of what they were up against. A screenshot began circulating among the nurses who had signed contracts with Professionals to USA. It was a summons from a Florida circuit court to a former Tallahassee Memorial nurse: If he did not respond within 20 days, “you may lose the case, and your wages, money and property may thereafter be taken without further warning from the court,” it read. “You may want to call an attorney right away.” Court records show that PTU is suing the nurse for $40,000, plus attorneys’ fees, for breaching his contract.

Fear radiated through the community of Filipino nurses in Tallahassee. Victoria heard that nurses who were planning to leave Tallahassee Memorial were reconsidering, and some who had left the hospital were now thinking of returning. For Victoria, too, the mental costs of opposing Raval have been high. She started taking anti-anxiety medication to help cope with the stress. She understands why other nurses may be afraid to speak out.

Even so, she’s glad she wrote the Facebook post — that she said something so that other nurses might be able to avoid a similar situation. “This is why this is happening,” Victoria said. “No one tried to correct it in the past, and no one warned us. So it just keeps going and going.”

Read more in our Merchants of Care series

Find the full series here.