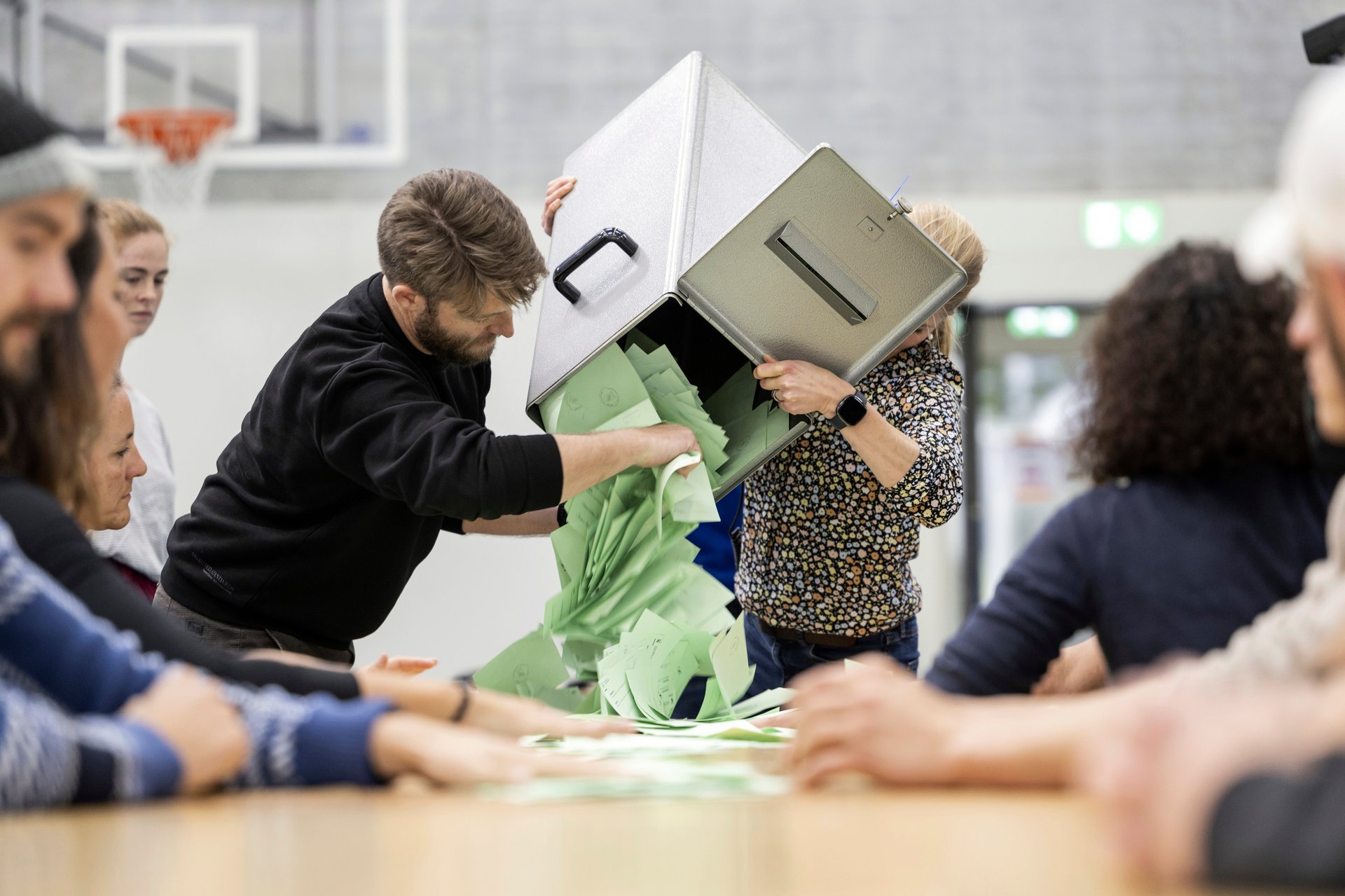

A Swiss populist party rebounds and the Greens sink in the election. That's a big change from 2019

Official results in Switzerland election show that the anti-immigration Swiss People’s Party has rebounded from searing losses four years ago to cement and expand its hold as the largest faction after the parliamentary election

GENEVA (AP) — Switzerland's anti-immigration Swiss People's Party rebounded from searing losses four years ago to become the largest parliamentary faction after the election, official results showed, as two environmentally-minded parties lost ground despite record glacier melt in the Alpine country.

Suggested Reading

Pre-election polls suggested that Swiss voters had three main concerns: Rising fees for the obligatory, free market-based health insurance system; climate change, which has eroded Switzerland’s many glaciers; and worries about migrants and immigration.

The final tally late Sunday showed the people's party, known as SVP by its German-language acronym, gained nine seats compared to the last vote in 2019, and climbed to 62 seats overall in parliament's 200-member lower house. The Socialists, in second, added two seats to reach 41 in that chamber, known as the National Council.

It marked the latest sign of a rightward turn in Europe, after victories or electoral gains by conservative parties in places like Greece, Sweden and Italy over the last year, even if voters in Poland rejected their national conservative government last week.

A new political alliance calling itself The Center, born of the 2021 fusion of the center-right Christian Democrat and Bourgeois Democrat parties, made its parliamentary election debut and took third place — with 29 seats, eclipsing the free-market Liberal party, which lost a seat and now will have 27.

Environmentally minded factions were the biggest losers: The Greens shed five seats and will now have 23, while the more centrist Liberal-Greens lost six, and now will have 10.

Political analyst Pascal Sciarini of the University of Geneva said Monday that the result was largely a “swing of the pendulum” and that support for the Greens was diluted in part because many voters felt they had already taken a big step toward protecting the environment by overwhelmingly approving a climate bill in June that will curb Switzerland's greenhouse gas emissions.

“At first glance, it’s a bit surprising because the climate crisis is even more present than it was four years ago — when climate worries were the dominant issue among the population,” he said.

He suggested that the bounce back for the SVP was a sign that rising insurance premiums and concerns about growing migration into Switzerland captured many voters’ minds this time.

“It’s perhaps that there was a sort of competition among concerns — and that made the job harder for the Greens to make climate concerns the dominant theme in the media,” Sciarini said.

Overall, the vote isn’t likely to have significant impact on Swiss foreign policy, he said. The country’s executive branch operates like a permanent government of national unity, where no single faction has total sway — what’s known among the Swiss as their “magic formula” of democracy to ensure balance and moderation, and ensure that personalities don’t dominate politics.

Even with their electoral victory, the SVP only holds just over 30% of seats in the lower house. The composition of the legislature, which is elected every four years, ultimately shapes the composition of the executive branch, which is called the Federal Council and includes President Alain Berset, who plans to leave government at the end of the year.

But the legislative vote result won’t significantly alter the composition of the Federal Council, where the SVP already has two seats — as do the Socialists, the free-market Liberals, while the Center has one.

The Center party, by outscoring the Liberals, may make a bid to swipe one of their two seats, and the Socialists will have to choose a successor for Berset; Those are the only likely changes to the Federal Council.

The Swiss president is essentially “first among equals” in the seven-member council, where each of the members hold portfolios as government ministers and take turns each year holding the top job — which is essentially a ceremonial one to represent Switzerland abroad. Berset will be succeeded next year by centrist Viola Amherd.

In Switzerland, voters also participate directly in government decision making. Voters regularly go to the polls — usually four times a year — to vote on any number of policy decisions. Those referendum results require parliament to respond.

More broadly, Switzerland has found itself straddling two core elements to its psyche: Western democratic principles like those in the European Union — which Switzerland has refused to join — and its much vaunted “neutrality” in world affairs.

A long-running and intractable standoff over more than 100 bilateral Swiss-EU agreements on issues like police cooperation, trade, tax and farm policy, has soured relations between Brussels and Bern — key trading partners.

The Swiss did line up with the EU in imposing sanctions against Russia over its war in Ukraine. The Federal Council is considering whether to join the EU and the United States in labeling Hamas a terror organization. Switzerland has joined the United Nations in labeling al-Qaida and Islamic State group as terrorists.

Switzerland, with only about 8.5 million people, ranks 20th in world economic output, according to the International Monetary Fund, and it’s the global hub of wealth management: where the world’s rich park much of their money, to benefit from low taxes and a discreet environment.